Photo: Sacramento Bee/Zuma

Back in 2000, an interviewer asked Norman Borlaug, father of the “green revolution” of industrial farming that swept through Asia in the 1970s, what he thought of the idea that organic agriculture could feed the world. The Nobel laureate became apoplectic:

That’s ridiculous. This shouldn’t even be a debate. Even if you could use all the organic material that you have–the animal manures, the human waste, the plant residues–and get them back on the soil, you couldn’t feed more than 4 billion people. In addition, if all agriculture were organic, you would have to increase cropland area dramatically, spreading out into marginal areas and cutting down millions of acres of forests.

The great man’s derision has clung to chemical-free farming ever since in elite policy circles. USDA chief Tom Vilsack occasionally pays lip service to organic farmers, but when he addresses the hard question of how to “feed the world,” he reliably toes the Borlaug line.

And yet, Borlaug was evidently wrong. It turns out, when you actually compare chemical-intensive and organic farming in the field, organic proves just as productive in terms of gross yield—and brings many other advantages to the table as well. The Rodale Institute’s test plots in Pennsylvania have been demonstrating this point for years.

And now comes evidence from the very heart of Big Ag: rural Iowa, where Iowa State University’s Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture runs the Long-Term Agroecological Research Experiment (LTAR), which began in 1998, which has just released its latest results.

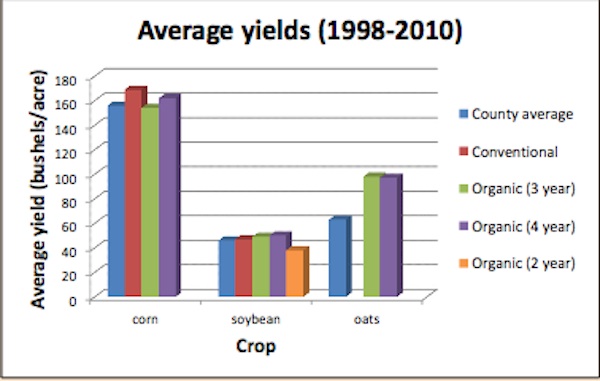

At the LTAR fields in Adair County, the (LTAR) runs four fields: one managed with the Midwest-standard two-year corn-soy rotation featuring the full range of agrochemicals; and the other ones organically managed with three different crop-rotation systems. The chart below records the yield averages of all the systems, comparing them to the average yields achieved by actual conventional growers in Adair County:

Charts: Leopold Center

Charts: Leopold Center

So, in yield terms, both of the organic rotations featuring corn beat the Adair County average and came close to the conventional patch. Two of the three organic rotations featuring soybeans beat both the county average and the conventional patch; and both of the organic rotations featuring oats trounced the county average. In short, Borlaug’s claim of huge yield advantages for the chemical-intensive agriculture he championed just don’t pan out in the field.

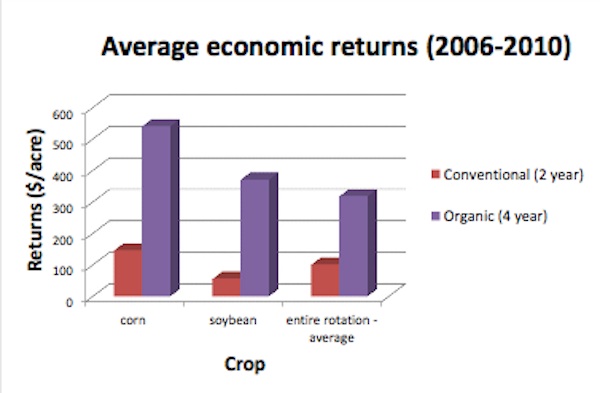

And in terms of economic returns to farmers—market price for crops minus costs—the contest isn’t even close. Organic crops draw a higher price in the market and don’t require expenditures for pricy inputs like synthetic fertilizer and pesticides.

Moreover, organic management improved soil’s ability to retain nutrients. “Total nitrogen increased by 33 percent in the organic system,” Leopold reports, and “researchers measured higher concentrations of carbon, potassium, phosphorous, magnesium and calcium in the organic soils.

So if organic farming offers equivalent yields, a dramatically higher economic return, and better long-term soil health, why aren’t more farmers switching over?

The last line of the Leopold Center’s report offers a clue: “Skilled management is an adequate replacement for synthetic chemicals.” Look at it like this: In the Corn Belt, technology and monocropping have reduced farming to a relatively simple endeavor. You douse your fields in synthetic and mined fertilizers and plant them in in corn one year, soy the next. When the inevitable plague of pests arrives—weeds and bugs love monocrops—you attack them with an arsenal of poisons. Then, you harvest and sell to vast multinational companies—Cargill and ADM—with the built infrastructure on the ground to make the transaction easy.

Farmers are understandably reluctant to switch away from that paint-by-the-numbers style. To make organic farming work, you have to stay ahead of the weeds and bugs by rotating in more crops than just corn and soy. And weed management requires other strategies just driving a chemical tank through the field or hiring a crop-duster: planting cover crops, tilling at just the right time, mulching. And selling, say, oats or alfalfa is trickier, because the infrastructure for marketing them has largely been dismantled over the past 50 years.

But that doesn’t mean that organic farming is impractical, as Borlaug insisted. It just means that we need to move public policy away from blind support for industrial agriculture (no easy trick), and learn to support the hordes of young people seeking careers in high-skilled, eco-minded farming.