Illustration: Harry Campbell

In America the birds can no longer be trusted. Our government suspects a duck or a goose, perhaps that rare swan, will bring plague to our shores. The ice is melting, also. The polar bears are fated to die, the seas are guaranteed to rise and flood our coasts. The skies have mutinied and new monster winds whip off the ocean. We’ve already lost one city and there is concern about future storms. We worry about nuclear weapons that are not controlled by white people. The government eavesdrops on many people and says this is necessary for our protection. The enemies can be anywhere and appear as almost anything.

The boy sits by the road on a dirt embankment in Arizona about four miles north of the Mexican border. His clothing is dark, his shoes casual. He wears a cap and a daypack. He is the face of yet one more official enemy. And he is lost and afraid. He’s been trying to flag down Border Patrol vehicles but he says they pass him by. He is 17 and afraid to give his name. He is afraid of the desert. He is afraid to talk of the coyote he hired. He is not afraid of the Border Patrol, but he cannot seem to get the agents’ attention.

The night before, he left Sásabe, Sonora, a small Mexican town of several thousand less than 10 miles away. He was hauled along the fence to the west and then started walking north in a group of about 30. A chopper with searchlights appeared in the dark, his group scattered and he could not find them again. A 26–year–old woman from Chiapas died near this spot last summer, one of the 400 or 500 who now perish each year crossing the border in this new version of the Middle Passage. But he knows nothing of that. What he fears is the desert of night that he just endured.

His father paints houses in Florida and knows the boy can get work. So he has brought his son north from Veracruz and guaranteed a smuggler $1,700 for his passage to Florida and then in the darkness all went wrong.

The boy wonders if his coyote will return for him. I tell him, Not likely.

He wonders if he can make a phone call using Mexican money. I tell him, No.

I point north to an Indian village just 500 yards away. I give him 20 bucks and say, Go there, give them the money, they will let you call your father in Florida. Most likely, the boy will be picked up by the Border Patrol, dumped back in Mexico, and tomorrow or the day after that join a new group of migrants, probably with the same smuggling organization, and move toward his future, again.

Mesquite clots the land here and a hundred people moving 50 yards away would be invisible. On the ground by the highway are clumps of one–gallon water bottles marking where coyotes picked up migrants. Nearby trees lining the arroyos hide temporary camps where men and women and children waited for rides.

Thirty years ago, I was in almost this exact spot with an old Indian man who still raised crops in the desert by capturing the summer rains, a tactic called ak–chin. At night he’d sleep in his field on a cot. He had ropes racing out from beside his bed and linked to suspended tin cans he’d rattle in the darkness when he heard coyotes—the real and native canines of the desert—come for his squash and melons. (Like humans, coyotes are omnivores.) Now that old man is dead, his field abandoned, and no one does traditional agriculture here. The tribe has moved on to welfare, casino gambling, and smuggling illegals and drugs.

One day, after I left that old man, I found two Mexicans wandering in the desert with gallon jugs of water. They had been walking toward farm work in the upper Altar Valley. But they’d been crushed by the summer heat and looked at me with broken faces. I put them in my car and drove them almost a hundred miles there without a thought. Now, I won’t drive a frightened boy 500 yards to a phone because I’m worried about getting busted by the Border Patrol and facing huge legal expenses.

Depending on the sector of the line, an estimated 10 or 20 percent of the Mexicans moving north give up after being repeatedly bagged by the Border Patrol. Or they do not. On the line, all numbers are fictions. The exportation of human beings by Mexico now reaches, officially, a half million souls a year. Or double that. Or triple that. What is for certain are the apprehensions by the Border Patrol (during one week this April, agents caught 12,434 people in the 262–mile Tucson Sector, for example). And that any reduction of poverty in Mexico takes two forms: the exportation of brown flesh to the United States, and the money those people send home to sustain the people, la gente, whom their government ignores.

Everything else is talk. And bad talk.

There are no honest players in this game. People cut the cards to fit their ideology. More Mexicans come north than either government admits. They do take jobs. (They say Mexicans take jobs Americans refuse to do. This is probably true in some instances. But in the mid–1960s slaughterhouse workers earned twice the current wage for their toil. Now such jobs are held by Mexicans.) They do commit crimes. And if the arrival of millions of poor people in the United States does not drive down wages, then surely there is a Nobel Prize to be earned in studying this remarkable exception to the law of supply and demand.

They are no longer migratory workers. And it is not seasonal labor. The people walking north all around me are not going home again. This is an exodus from a failed economy and a barbarous government and their journey is biblical.

And all the solutions in political play are idiocy. Worker permits? Demand at this moment is certainly the 12 million illegals in the United States today, and it climbs each year by maybe a million more. Open the border? Mexicans would be trampled to death by Asians storming up the open route and, also, by other Latin Americans, those folks the Border Patrol calls OTMs, Other Than Mexicans. Build a wall? The border consists of 1,951 miles of desert, mountains, and scrub, a zone legally traversed by 350 million people a year–the busiest border in the world. Employer sanctions to make illegals unemployable? Fine, then Mexicans go home and Mexico erupts and we have a destroyed nation on our southern border and even greater illegal migration. In 1910, the Mexican Revolution ripped apart a nation of 15 million souls. One out of 15 died. But 892,000 fled to the United States. Now there are 108 million Mexicans. Do the math.

There are piles of studies on these matters, studies that prove illegal migration benefits the United States, studies that prove it does not benefit the United States, studies that show it enhances the GDP or has little or no contribution to the GDP. There are plans to manage this migration and plans to stop it dead in its tracks. There are proposed solutions. And, of course, there are claims that we don’t really need a solution, because mass migration is natural for a nation of immigrants and as American as apple pie.

But in the end, you don’t get to pick solutions. You simply have choices, and by these choices you will discover who you really are. You can turn your back on poor people, or you can open your arms and welcome them into an increasingly crowded country and exhausted landscape.

I think this country already has too many people and that the ground under our feet is being murdered and the sky over our heads is being poisoned. I find these beliefs pointless when I stand on the line.

Across it flows the largest migration on earth. Nearly 15 percent of the Mexican workforce now resides in the United States. When the dust settles, this exodus will influence us more than the Iraq war. The war is who we are; the migrants are who we will be. For a century, the United States has tolerated and sponsored various nondemocratic rulers in Mexico. When Porfirio Díaz ruled as a dictator, we celebrated him. When the revolution came, we tried to corrupt and control various factions and repeatedly invaded. When a new dictatorship settled on Mexico disguised within single–party rule for 71 years, we celebrated it. When the students were butchered in Mexico City in 1968 on the eve of the Olympics, we focused on gold medals and ignored the murders. When Mexico became a narco state in the 1980s, we denied this fact. When NAFTA proved ruinous to most Mexicans, we denied this fact. And now as millions flee this charnel house, we pretend it is simply a mild structural readjustment of globalization, something that provides us cheap labor and grows that thing we call our economy.

For several decades now our economic theology has outsourced not only American jobs but also the reality that most people on this planet must endure. We buy clothes made by children and comment on the good price. Oceans have largely sheltered us from the consequences of our actions. But the Third World has finally said hello and this time not even a wall will keep it silent or at bay. What is happening on our southern border has penetrated our entire country and the border is simply a point where we watch the world race toward us at flood level. The issue is not securing a broken border any more than the real issue in New Orleans is building a better levee. Storms are rising, and the walls and levees are simply points where we taste their initial force as they move inland.

We have entered the future even as we pretend it is simply a version of our past.

Some of us protest this future. Kyle, 37, wears a camouflage hat and a green T–shirt. He’s a man of some heft and does not smile easily. He’s getting ready for a patrol at a ranch house about 40 miles north of Sásabe. It’s early April, and the Minutemen are bivouacked just above the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge. Last year, Kyle took part in the Minutemen’s initial action, an event of media brilliance that recalled guerrilla theater masterpieces of the ’60s. With only a few hundred people, mainly retirees, the Minutemen, outnumbered by print, radio, and television media, captured the imagination of many Americans, caused a national conversation about the perils of the border, and danced across television screens for weeks. Their leader, Chris Simcox, came off as a smooth–talking John Wayne defending a new Alamo. I liked them all and thought I had stumbled into a geriatric Woodstock. To avoid any unseemly incidents, Mexican soldiers had told the coyotes to take a holiday and so the entire month was tenting, talking, lawn chairs, and not much else.

This year is different. Like so many outsider movements, the Minutemen have had their thunder stolen by the mainstream pols. Their issues are now legitimate talk on the floors of Congress. But still Kyle’s here to “protect the American Dream, live in a free country, own a home, and make a decent living without tyranny.”

Kyle owns a kind of janitorial service in the Phoenix area, and in a few days that city will host a march by illegals protesting the bill in Congress that would make them felons, deny them a chance for citizenship, and possibly deport them. He says a bunch of his employees have told him they are going to skip work for the march.

He begs to differ. “You can’t,” he offers, “legitimize 15 to 30 million lawbreakers. There’s some people here who plain shouldn’t be here.”

Just then, Chris Simcox ambles up. He’s dressed in black and holds a hacksaw in one hand (he’s been cutting PVC pipe) and a cigar stub in the other.

Simcox is a natural American genius at publicity. “We’re going to grow,” he explains, “until we equal the number of the Border Patrol if we have to. We have 7,000 members and next year we’ll have 14,000 to 15,000. We have Americans here taking jobs that the government won’t take. Try and remove us.”

He speaks darkly of an incident like Tiananmen Square should the authorities try to remove Minutemen from their stations.

He loves the marches by illegals and their supporters. “It’s already backfired,” he says. “We couldn’t ask for a better situation–hundreds of thousands showing no respect for this country. The silent majority is not out there yelling and screaming.”

In a few days, Simcox will unleash his new idea: have the Minutemen build fences on private property along the line to demonstrate that the U.S. government could easily stop this brown invasion of America. First, there will be a 6–foot–deep trench backed by coils of concertina wire and then a 15–foot–tall steel mesh fence with the top angling toward Mexico. Behind this will be a dirt road and video cameras so that anyone on a home computer can watch for illegals. Across the road will be another 15–foot fence and more concertina wire. The group figures the whole deal will run only $125 to $150 a foot.

I stroll around the corner and see the tally board. One day the Minutemen‘s morning shift sighted 92 illegals and bagged 34. The midday shift saw 83 and caught 59. The night crew sighted 54 and nailed 23. These numbers stun me because they mean that, unlike last year, the coyotes have so many customers they cannot afford to avoid routes known to have Minutemen plopped in their path. Imagine rush hour and you see the reality. Of course, bagging the quarry means calling the Border Patrol to pick them up. The Minutemen are punctilious about the niceties of law, and what they are doing—armed patrols against lawbreakers—is legal.

They are the inevitable consequence of illegal immigration, part of a new page in American nativism. They are neither alarming, nor unfriendly, nor relevant.

Forty miles south of the Minuteman camp, I hit the drag road, a dirt track swept by the Border Patrol looking for the footprints of men, women, and children heading north. The ground is littered with cast–off water bottles, clothing, food cans, shoes, gloves, backpacks. The Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, covering about 185 square miles, was created by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1985, in part to save the masked bobwhite, a bird that was extinct in the United States and barely clinging to life in Mexico. What killed off the bird was settlement in both nations. Now it is being slowly stomped to death in its last refuge. Migrants have created 1,320 miles of trails and resurrected 200 miles of old roads, now littered with abandoned cars, some decorated with bullet holes.

I load my truck up with trash and head out to the main gate. A pair of Border Patrol trucks sit empty, the agents off on ATVs hunting Mexicans. Two kids sit nearby. The girl is 22; her brother, 16. They’ve been trying to flag down Border Patrol units that roar by, but no one will stop. They came up from Oaxaca City. They’re Zapotec Indians, but because they haven’t been raised in an Indian pueblo, they see themselves as city kids, as Mexicans. For 16 days, they’ve been on the road.

First they took the bus up to the border. Then they paid a coyote $800 to guide them across. The first time, they got caught and deported. This time, they got separated from their group and they say they have now wandered the desert for four days. I don’t believe them about the four days—they look too clean—but clearly they are broken in spirit.

They’re headed toward friends in Madera, California, a spot outside Fresno. But for now, they want to go back to the border. They need to reconnect with the smuggler (coyotes usually include three attempts in their price) and make a call to their people in California. And they need to eat and drink. The boy, despite my warnings about the trash I’ve collected off the migrant trails, grabs from this garbage a bottle with some pop left in it and guzzles.

He weighs maybe 110 pounds, and she not more than 85. They are small–boned and their skin is dark and shines with life. Both move with the light tread of cats. An hour ago, I found a shawl out in the desert of a pattern and style made only in Yucatán. Everyone is moving.

More than 40 years ago, when I was a boy starting to notice the way girls moved when they walked, I camped on a street in Durango, Mexico, with my old man in a bread van he’d converted into some notion of a camper –– a slab for him to sleep atop cases of beer, a Coleman stove, and the floor for my bunk. It was hot and he opened the back doors and tossed a canned chicken into a pot for his idea of a meal. Soon a gaggle of kids gathered with hungry eyes. The old man stood there with his hand–rolled cigarette and then started giving out cans of food –– potatoes, chickens, corn, beans, Spam, hash, all the staples of his menu. When he was done and all our food was gone, I asked him why. He said nothing but opened a quart of lukewarm beer from the reserve he slept on. I knew he’d come up hard, but it was years before I understood what he taught me that night.

I give the girl $40 and tell her to hide the money because Sásabe is not an easy place. They climb in and I take them to the border crossing and wish them good luck. The agents manning the U.S. station watch them climb out and walk into Mexico.

They ask me if the pair worked for me, and I say no, that they are two kids from Oaxaca sneaking into the United States, that they said they’d wandered in the desert for four days and were very thirsty and hungry.

They tell me what I have just done is illegal and could cost me a lot of money and put me in jail.

I say I know that fact.

They look at me with sad eyes and wave me on.

It’s not easy for anyone in the future.

In phoenix, 200 miles to the northwest, Mexicans have always been present but not accounted for. Fifteen years ago, I was talking to the publisher of the city’s major lifestyle magazine, and when I mentioned Mexican Americans as an element of the city absent from his slick rag, he looked puzzled and suggested there were a few around doing gardening. Recently, the metropolitan area has been growing like a weed, choking out the desert with subdivisions. And a large part of the growth has been illegal migrants. Home invasions have exploded as rival gangs steal migrants from stash houses, which now number more than 1,000 in Phoenix alone.

In mid–March, the local Spanish–language radio stations promoted a protest at U.S. Senator Jon Kyl’s Phoenix office. The senator had tossed some tough provisions into an immigration bill. Twenty thousand people showed up. Until then, Phoenix had feasted on golf, traffic jams, and sun and remained largely oblivious of a secret city within the city. Now, after the massive protests in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Dallas, Phoenix joins a national network of marches on April 10. The city simply waits, silent, a bit worried and at the same time curious: Just how big will a gran marcha be?

The parade route sleeps in the early morning light as men unload cases of water at aid stations along Grand Avenue. Inside Mel’s, a hash house decorated with American flags and slogans (“Let Freedom Ring”), the manager talks in Spanish with three young illegal guys about some remodeling; each wears big decals with the march slogan, “Somos America” (We Are America). The back room is wall–to–wall cops chowing down and plotting how to handle the marchers. The customers, buzzing about the event, are black, white, and brown, and one black guy pretty much sums up their attitude: “As long as they do it right, it’s okay.” Frank, 47, who’s Mexican American, sounds the only dissent. He’s pissed by the display of Mexican flags in the earlier march on Kyl’s office.

He’s got huge tattoos on each arm and a quick mouth that says, “They got more rights than we do. They got cars, cell phones. I was born here, worked all my life, I can’t get no car. They talk about how wonderful Mexico is, well, kick their ass back there then. I take the day off, I lose my job. They ain’t gonna pay my rent.”

He rolls on about how his mom’s neighborhood is overrun with illegals living 7 to 10 to a house. Then he turns to a customer and instantly shifts into Spanish.

Around 10 a.m. at the march’s origin point, the state fairgrounds, bands and speakers entertain maybe 10,000 people. They are all ages and they are all brown. It is difficult to give simple categories such as legal and illegal. Take the Garcia family.

Sandro’s been here 14 years, was brought north by his farmworker dad. He has some kind of papers. Next to him is his wife, and she’s illegal. She holds their child, a girl Sandro calls Pretty Girl, who is a U.S. citizen by birth. Technically, this family has one illegal, but as a state of mind, they are all migrants, all living and working in a kind of shadow world. And they all are festooned with small American flags.

Police and media choppers hover overhead. The crowd chants, “Sí Se Puede” (Yes, It Can Be Done). A burly young guy has an American flag sprouting out of his hat and a huge tattoo on one arm that reads “Hecho en Mexico” (Made in Mexico). All this is watched by Pete Rosales. He did Nam in ’64 and ’65 and has a big scar on one leg as a keepsake of that frolic. He’s been watching the crowd since 7:30 a.m. “to make sure they get it right.” And getting it right for him means no more of those damned Mexican flags and lots of people so that the gringos will stop treating Mexicans like second–class human beings. He needn’t worry –– those few who arrive at the fairgrounds with Mexican flags are pounced on by march organizers.

At 12:25 p.m., the march steps off. I’ve seen flash floods roar down desert arroyos, the wall of brown water churning and tumbling. Now I see one made of human flesh. For more than two hours, la gran marcha sweeps past me. The people fill Grand Avenue from building to building. There is no space for spectators except on rooftops. The lines flooding the street are at least 60 people across. Each line takes one to two seconds to pass me and features three to four baby strollers. The water station next to me is gutted in 50 minutes flat. And still they keep coming. In two hours, I see maybe 10 whites, 1 black, and no more than 30 Mexican flags. And at least 50,000 American flags: flags fluttering from poles, flags held in hands, decorating cowboy hats, sprouting from manes of black hair on the heads of mothers pushing strollers. The signs are almost all the same: WE ARE NOT CRIMINALS, WE ARE AMERICA OR TODAY WE MARCH, TOMORROW WE VOTE. A herd of Prussians could not be more organized and on message.

When it is over, there will not be a single reported incident. Nothing but at least 200,000 people peacefully walking down the street of the city that ignores them. And I never see a single can of beer. This is the largest gathering of human beings for any reason in the history of Arizona. The state press is largely silent about the march. It was too big, now what? Deportation begins to sound like a pipe dream. After all, this is the nation that could not get 100,000 of its fellow citizens out of New Orleans and to safety.

In Mexico

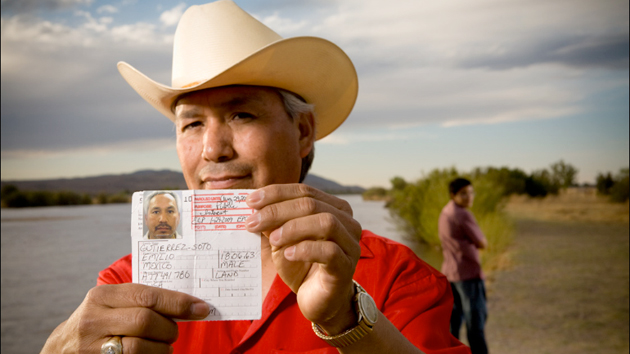

Yellow dogs laze in the afternoon of the plaza. Altar, 60 miles of dirt road south of Sásabe, is home to 18,000 people and a way station for 500,000, 600,000, 800,000 souls a year who pass through on their way to El Norte. A month ago, an undercover Border Patrol agent surveyed the traffic and pegged it at 5,000 people a day. No one knows for certain and hardly anyone really wants to know. But you can go to the bank with this: Each year more Mexicans move through Altar and illegally enter the United States than our government admits illegally cross the entire 1,951–mile border. Altar is the beginning of the lie and the beginning of the pain.

Two things happen to visitors in Altar: first stunned silence and then a search for some metaphor to wrap around the dusty town. A visiting novelist, Phil Caputo, noticed the 20–odd stalls selling black daypacks, black T–shirts, and other clothing and deemed it a migrant Wal–Mart. On the east edge of the community is a boardinghouse for migrants named Éxodo, Exodus. There are dozens of such flops in town.

Here is the basic script: You get off a bus you have ridden for days from the Mexican interior, increasingly from the largely Indian states far to the south. This is the end of your security. On the bus, you had a seat, your own space. Now you enter a feral zone. With money, you can buy space in a flop ($3 a night) and get a meal of chicken, rice, beans, and tortillas (about $2.50). You stare out on an empty desert unlike any ground you have ever seen. Men with quick eyes look you over, the employees of coyotes, people smugglers. On the bus, you were a man or a woman or a child. Now you are a pollo, a chicken, and you need a pollero, a chicken herder.

You will never be safe, but for the next week or so, you will be in real peril. If you sleep in the plaza to save money, thugs will rob you in the night or, if you are a woman, have their way with you. If you cut a deal with a coyote’s representative (and 80 to 90 percent do), you still must buy all that black clothing and gear, house and feed yourself. Then one day, when you are told to move, you’ll get in a van with 20 to 40 other pollos and ride 60 miles of bumps and dust to la línea. Each passenger pays $25. The vans do not move with fewer than 17, prefer at least 20, and do, at a minimum, three trips a day. A friend of mine recently did the ride and counted 58 vans moving out in two hours.

Fifteen miles below the border, you will face a checkpoint set up by Grupo Beta, the Mexican border patrol that’s supposed to help pollos. Early this year, a group of American reporters stood at the checkpoint and counted 1,296 people in 180 minutes. Signs there warn of venomous creatures and high desert temperatures. The officials are under an orange ramada, one with a crudely painted single word, gallo, rooster. The vans stop; their bodies are beat up but the tires, always, are excellent. You will be sitting inside, possibly on an iron bar so that dozens of pollos can be packed in. The men of Grupo Beta will count you –– everyone gets a cut in this business. The head of the state police in a town just ahead on the line is said to take in $30,000 a week.

At the moment, though you are penniless, unemployed, and frightened, you are worth a few hundred dollars, almost like an oil future. But you must get to that stash house in America before you are worth real money and worth protecting. And you must do it by force of will. In this sector of the line, the 262–mile–long Tucson Sector, a few hundred will officially die each year. Others will die and rot in the desert and go uncounted. A year ago, a woman from Zacatecas disappeared in late June. Her father came up and searched for weeks to find her body in the desert, a valley of several hundred square miles. He stumbled on three other corpses before finding the remains of his own child.

At dusk, you will go through the line with 20, 30, or more Mexicans. There will be a guide. You will carry a gallon of water and that black daypack. The temperature in summer could be 115 degrees. You will walk anywhere from 10 to 60 miles, depending on the route and what you have agreed to pay. There will be rattlesnakes, cacti, trees. And almost no sign of people. Everything will have thorns that rake your skin as you stumble through the darkness. You will keep up or be left behind. If you are a woman, you have a fair chance of being raped. And you will most likely never speak of these nights again so long as you live. You will have children and grandchildren and teach them many things. But if you are like the others who have passed this way, these nights will remain your secret.

The middle passage ends at the stash house in Tucson or Phoenix. The price from there to distant spots –– North Carolina, Los Angeles, Chicago, and so forth — is $1,700 and rising. And this price does not cover getting to the border or crossing the border or food or a place to stay. It only covers getting from the stash house to another destination in Los Estados Unidos.

Somewhere between Altar and Phoenix, new Americans are being forged in a burning desert. No one is really counting the people, no one is really recording their journeys. Soon, they and their descendants will number 30 million. And this vast silence is likely to be the savage part of their repressed history.

On the plaza at Altar, pollos sit in rows, waiting for their van rides. They wear dark clothing and have daypacks and gallons of water by their side. Inside the church, they often light $1 votives before heading into the desert. A mile to the west, two new motels have risen, one mainly for pollos, the other for polleros. A tourist would have a hard time finding lodging in Altar.

Everywhere around Altar, new houses are coming out of the ground. The nicest run 2,000 to 5,000 square feet, have fine windows and doors, good walls surrounding a lot of flowering trees and shrubs. These belong to drug traffickers, sharks who swim in the same sea as the migrants and find that thousands of pollos mask their own hikes with backpacks full of dope. They tend to carry AK–47s as well as water bottles. The going rate for moving marijuana across the fence is $10 a pound — one night hauling a 100–pound pack can mean $1,000. There is a fantasy that drugs and migrants are separate matters. Both are moved by the same organizations and both come north to satisfy American hungers — those seeking people who will work for low wages and those seeking highs. And both mock the pretenses of Homeland Security.

Near the plaza are two guys from Guerrero in the regulation pollo black. They are Indians and plan to go to Taylor, Texas. They say they have friends there — pollos always say they go to friends, not family, an act of caution.

One guy, 19, gives the basic biography of a pollo: “I have never been in the U.S. before. I plan to spend a couple of years, and then go back to Mexico. There are no jobs in Guerrero. Why even go to school? When you graduate, there are no jobs. Last week, in the state capital I saw 300 young schoolteachers demonstrate because they could find no jobs. I work in the fields. I can grow beans, corn, and squash.

“His eyes are anxious. He has heard Americans think people such as himself steal jobs from them. But he does not believe this because “people who have been in the United States tell me Americans don’t work in the fields.”

He has two worries: dying in the desert, and not finding a job. He’s heard of the recent big marches and thinks people have a right to march.

“Why,” he asks, “won’t the U.S. let us work and then go home? We don’t want to do anything bad to America. In my village, 20 percent of the people have gone to the U.S., and in the state, about 50 percent have gone. I’ve been in Altar two days waiting to cross.”

This story plays out of mouth after mouth in the plaza. There is no work in Mexico. Do you know where Oregon is? Do you know where Tennessee is?

Juan Hernández, a dark Mixtec Indian who has already been caught once by the Border Patrol, explains, “There is no work, no rain, nothing to do in the fields. We are very poor there. I don’t know what the U.S. is like,” but, he adds, already 20 to 30 people from his village have gone to America.

In the stalls, black T–shirts say “Retired Army” or “U.S. Navy.” They sport huge American flags or soaring bald eagles. Racks hold medallions of Jesus Christ and Jesus Malverde. One was said to be a carpenter, the other a bandit hung in Culiacán, Sinaloa, in 1909 and now a favored santo of the narcotraficantes. A line snakes out of the telegraph office where pollos wait for money orders to pay the coyotes; others line up at the pay phone, checking in with relatives despite some of the highest phone rates in the world.

There are two sounds: pigeons, and the low rumble of vans as they load pollos.

Francisco Garcia, 39, has smooth skin, black hair and mustache, and the slack gut of a man who does not work in the fields. Until recently, he was the mayor of Altar. Now he works for the Catholic aid center for migrants six blocks off the plaza. Those defeated by the desert and the Border Patrol come here for food and shelter. And then they head north again — Garcia knows one migrant who tried 25 times before he succeeded. He thinks at least 90 percent of the migrants get through.

He explains that the traditional economy of Altar was cattle and farming. Now it is pollos and drugs. “The migrants are like a curtain that hides the money of the drug business.” Almost all the people in the pollo industry — the people running phone services and boardinghouses, the coyotes — come from outside Altar.

He describes the people–smuggling business as like a string of rosary beads, with each bead a self–contained cell. In the Mexican south, men recruit pollos, then other men round them up and ship them on buses to, say, Altar. Here another cell plants them in flophouses and arranges van rides. Sixty miles north, another cell moves them through the wire. At the end of their desert trek, they brush against the next cell, which loads them in vans and takes them to stash houses. Here a key representative of the coyote arrives, copies down names and phone numbers and destinations, makes the calls to tell the pollos’ relatives of the charge. Sometimes these people double the price from what had been earlier agreed. After forking over half the fee, the pollos are loaded into vans according to their destinations. On arrival, another key figure appears, some blood kin of the coyote, who pockets the rest of the money. The top coyote remains in the shadows, Garcia says, an intelligent, cunning, and mysterious figure.

This year he thinks 800,000 Mexicans will pass through Altar on their way to El Norte. The sign behind his desk advises that Jesus, Mary, and Joseph were migrants looking for a better life.

Down at the plaza, people line up at the public restroom (three pesos a visit). Outside, buses keep arriving and unloading people from the south. Two pollos stop at a stall to buy foot powder before climbing into a van. Vans depart more and more frequently. They will haul Mexicans until at least 8 p.m., people who, if everything goes per schedule, will move through the wire on Good Friday. Where the road leaves Altar and heads north into the desert stand three crosses. One says “Children,” the next “Family,” the third states that “2,800 have already died on this journey and how many more must die?” The town priest put them up. Then he was shipped to the Vatican where he couldn’t make such a fuss.

In America

The minutemen’s Line Bravo runs five miles. Just beyond the end is an old stock tank. Bob Kuhn parks here. He’s past 70, did his stint in Korea, and last year was Chris Simcox’s bodyguard. Kuhn is a land surveyor out of Phoenix, a family man who has worked hard all his life and now devotes time to the Minutemen and also to a machine he’s designed that will make electricity for free. He tells me he’d love to go to Altar and see all those coyotes and pollos, but alas, MS–13, a Central American gang, has put a $50,000 reward out for his head. He heard this through “the underground.”

We walk up a slight rise and then it slaps us in the face. The mess flowers like an ink stain over the desert, the ground literally blackened by tossed daypacks and clothes and underclothes. I’ve spent days cleaning up dump sites and never seen one remotely of this scale. I’m sure U.S. intelligence satellites can watch Mexicans molt into Americans at this place.

Kuhn and I fall silent. The ground feels haunted. There are hundreds, thousands of daypacks. I pick up a dark blue brassiere with lace, the straps torn by wear. The woman must have been very small and very young. There are panties everywhere, along with spent bottles of water, electrolyte mix, fruit juice, chilies, razors, toothbrushes, canned fish, all manner of soaps and foot powders, rolls of toilet paper, a canister of Instant Quaker Oats, shoe polish, Brut underarm deodorant, a toenail clipper, a spool of thread, a bottle of Vicks Formula 44, hair gel, a thick Spanish–to–English dictionary. I pick up an eye–shadow case, the cells of color barely touched. The woman had a choice of white, opalescent pearl, Prussian, taupe, Naples yellow, rose, lavender, slate, raw sienna, viridian, broken viridian, and chocolate taupe. And possibly work and America. Mexican airline and bus tickets are scattered about. Aurelio Pérez, a child, got aboard a bus at night, for example.

A deck of tarot cards is strewn about the ground. Antonio Hernández Salinas has forgotten his high school records — he was studying math, English, and ethics in the state of Hidalgo. Tucked into one daypack is a letter in Spanish with the block printing of a seven–year–old, probably a girl. She wrote, “for my father, dad I love you too much for giving me so Much from Yourself and I wish you a Good trip in the Airplane When you Travel to the united states and god take Care of You in the airplane.”

I sit on the ground for an hour or two. Ravens and hawks come by, the wind rustles the trees. Tied to one daypack is a small stuffed dinosaur named Sugarloaf and made in Indonesia. There’s a dirt road a short ways to the north. The pollos have walked two days to reach this spot to meet smugglers who’ve brought American clothing so they will look normal. They rapidly strip naked — bras, panties, blouses, shirts — everything is cast aside. Hurry, hurry, they are told. And so a good father who lies to his little girl can sometimes forget the letter he has been carrying to help him find the will to cross the desert.

Then, decked in clean clothes, the pollos crowd into vans and are taken to stash houses in Tucson and Phoenix. I’ve stumbled onto their Ellis Island where their past slips from their grasp and their new life is hastily pulled onto their naked bodies.

I can’t tell you his name. I can’t tell you where he works. I can’t tell you much but this: He came up in the gangs of his American barrio, and then at 19 he caught a break and became a drug dealer. His operation is smooth, reaching down to his suppliers in northern Mexico and far into the U.S. interior. But now, like so many with his background, he’s shifting into people smuggling.

For the moment, he helps out at stash houses. He’ll go to Costco and buy cases of Campbell’s soup and, say, a half–dozen can openers. Then he’ll go to a stash house. A pistolero will be there to guard the pollos so they cannot be stolen.

The man with the cases of soup will carry them in and hand out the can openers. The house will be rented and in a middle–class neighborhood. There will be no furniture, and such houses are changed often. Of his work he says two things: how bad the houses smell with 30 or even 100 people crowded into them. And how nice some of the young pollo girls look.

But he insists he resists all temptation. He sticks to “Dos Cientos,” the maquiladora girls who are brought up from the Mexican factories just across the line to decorate parties. They are each given $200, and for that, he tells me, the girls will “give you that massage that sends you to heaven.”

He is a very intelligent man. His favorite magazine is GQ. He dreams of owning a Cadillac Escalade.

But that smell in those houses, he repeats, it is terrible.

He is in a hard business. Recently, a man sat in a local café and offered $50,000 for anyone who would murder his boss, who happened to be his uncle. His uncle heard of this offer and came down to the café and pistol–whipped his nephew half to death, all the while shouting, “How could you insult me so? I am worth more than $50,000.”

I ask him how many guys he came up with in these businesses are still operating or even alive. He falls silent for a minute or two. He cannot think of many, he replies.

We talk for hours. He laughs easily, but not for a single second does he ever express sympathy for the pollos. After they get off that bus and start north into the United States, they fall between two worlds, and people such as him wait in this space.

He is not a bad man. The Border Patrol agents are not bad people. The Minutemen, the polleros, the human rights folks putting water bottles out in the desert, well, I’ve met them all and they are not bad people.

As for you and me, the jury is still out.

The woman left a village in Oaxaca, traveled through Arizona, and arrived in Eureka, California. She is 30, has five children. She knows the name of her village in Oaxaca but cannot name any place near it. She knows Eureka and its Oaxacan community but nothing else of the United States. Two of her children are U.S. citizens, but she has no identity beyond her family. She is overwhelmed by a new world and so she concentrates on cooking. She answers to no pathway to citizenship, nor is she up on the global economy. She is what all the politicians are talking about and yet she understands not a word they say. She came to America because the tightened border increasingly means the men hardly ever return home to Mexico. And so she huddles in Northern California where the men toil in the lumber mills or tend plants in nurseries.

Martín now has papers. He began crossing 20 years ago to jobs in south Texas. The first time, a coyote took $200 and then vanished. The second time, he walked for days through scrub, reached the promised van but was seized by the Border Patrol. Once he toiled 30 days in the melon fields and then found that the farmer had called the Border Patrol so he could avoid paying his illegal laborers.

Martín’s son–in–law came through the line about 70 days ago. He called a number in America from his village in Mexico. The man sent a guide to bring him across the river. He spent two days in the coyote’s house waiting. Then the man came and said, Put on this soccer uniform. The man said, If the Border Patrol agent asks you where you are going, you say, “San Antonio.” If they ask you if you have papers, you say, “Yes,” in English. They practiced these simple answers. Then they rode up to the U.S. checkpoint. The Border Patrol agent asked the two questions, got his answers and waved them through. In San Antonio, the coyote took back the soccer uniform.

The coyote has pulled this same stunt at least 50 times in the past year at the same checkpoint. Sometimes he moves two people, usually one. They must be young and look fit. For this he charges $2,000. He never fails. You can believe the coyote is unusually lucky or you can believe U.S. agents are on the take. Martín’s son–in–law never asked nor does he care. He can make a good living doing construction in Dallas and that is all he cares about.

Víctor tends a stable of horses in south Texas. His wife is American, and he is raising the boy of another Mexican who is going to be in a U.S. prison for a long time. Víctor works across the street from a county jail, but none of the cops ever bother him. He is a lean and dark man and he is about work. For six years he worked in Juárez right across from El Paso, first at an rca plant and then doing construction. He never thought of crossing. And then he began hearing from friends in his native village about the good jobs they’d found in the United States. And so he came here and put down roots. He says he had a dream recently, and in that dream he was in Mexico. He awoke terrified and thinking, “How will I get together enough money to pay a coyote and escape Mexico?”

That is the line. Fragments all saying the same thing: Get out.

In Mexico

She waits by the fork in the road. El Puente del Comercio Mundial, the World Trade Bridge, is on the new truck highway that each day feeds 5,800 semis in and out of the twin cities of Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, and Laredo, Texas. This is all part of the SuperCorridor, a huge construction project designed to speed the flow of NAFTA trade. Big new ports on Mexico’s Pacific coast will drain the freight from Long Beach and other California docks. The products of Asia will be unloaded in these harbors safe from the maritime unions and then sped north by Mexican truckers safe from the Teamsters union. The drivers will deliver these loads anywhere in the United States. At the moment, such Mexican truckers put in about 50 hours a week and earn around $1,100 a month. They all have wrecks, they all use drugs, and they all work like beasts–one run from Ensenada to Cancún takes five days and six nights and no one stops for sleep or anything else.

That is why she is here. The first little capilla appeared five years ago at the interchange of I–35 and the World Trade Bridge. Now there are three more chapels, each large enough for a man to enter. Trucks idle on the shoulder of the highway as men approach La Santísima Muerte, Most Holy Death. She is the saint for drug dealers and for truckers and for anyone else who understands that the game is not on the level and help is necessary for survival.

La Santísima Muerte has no flesh — her bony feet and hands reach out from her cloak. One hand holds a huge scythe, the other the world. She looks like death but promises a chance at life to those whirling in a world of death. In Nuevo Laredo, 230 people have been slaughtered in the last 16 months as a byproduct of the drug industry. In February 2006, two men entered the daily newspaper, sprayed the office with assault rifles (the lobby still has more than 20 bullet holes), cut down some staff, threw a grenade into the editor’s office, and then left after 180 seconds of commentary. The paper decided to cease publishing stories on the cartels. When four cops were executed on a downtown street this past spring, the news was broken by Mexico City papers 700 miles to the south. Yesterday, a cop guarding the assistant police chief’s house was mowed down. The paper buries this story in the back facing a feature on a local honey cooperative.

A trucker in his early 20s stands before La Santísima Muerte, his voice very soft as he speaks to her. He says, “She is just like us, except she has no flesh. She can speak to God. She has helped me many times.”

Once he saw her standing by the road. She saves him when the highways are wet and saves him from wrecks and saves him from police and saves him from the many faces of death. He enters the main capilla, lights a cigarette, and leaves it burning for her. The altar is rich with candy bars and fruits and money.

He explains, “I have believed in Santa Muerte since I was 13 years old. If I tell you of her favors to me, I will never cease talking. I have a shrine to her in my house and offerings of rice, tomatoes, wine, apples, corn, and bullets.”

A man of about 40 climbs down from his truck. He wears black, dark sunglasses, and a gold chain. He stands before La Santísima Muerte and softly speaks to her as he sprays her body with perfume. An expensive two–seater sports car rolls up. The occupants do not get out but sit in their machine a few feet from La Santísima Muerte, praying as the air conditioner roars. No one looks at them because everyone knows how expensive sports cars are earned here.

She first appeared during the late ’90s in Tepito, the thieves’ market of Mexico City, a zone of 37 blocks stuffed with contraband, whores, addicts, live sex shows, and violence. The priests were alarmed but could do nothing because La Santísima Muerte exuded tolerance. Women went to her to be safe from AIDS and to ensure their clients remained docile. Men sought protection from bullets. She spread north to the line and then spilled over into the ragged neighborhoods where migrants hid from view in the cities of America. The anthropologists pounced and concluded she had erupted from the long–dormant virus of Aztec death worship.

I think she is the saint of NAFTA. In 1994, the trade agreement first kicked in and within a year the numbers crawling through the wire began to spike. Within three years, La Santísima Muerte had entered the minds and hearts of those broken on this new notion called free trade. NAFTA crushed peasant farmers who could not compete with the torrent of cheap agricultural products flowing from American agribusinesses. Trade with China, Mexico’s introduction to the global economy, swiftly wiped out traditional industries: toys, serapes, shoes, and so forth. Then the border plants, the maquiladoras where Mexicans assembled goods for American corporations, closed up shop and hightailed it to China where men and women work for one–fourth the wages of Mexicans. Juárez, the poster child of free trade, lost 72,620 jobs to China in less than three years, for example.

In Nuevo Laredo near the Rio Grande, a market stall sells statues of Christ, the Virgin of Guadalupe, Emiliano Zapata, and La Santísima Muerte–who outsells all the others combined. She touches more human behavior than the Border Patrol or Homeland Security or the DEA. She holds the whole world in her bony hand. For years, she succored the souls being displaced and hurled north, listened to their fears and hungers while politicians talked about slight adjustments in the global economy, while others spoke of guest worker programs, as some babbled about pathways to citizenship, as growing numbers rumbled about building big walls on the line, and still others explained the need for workers to perform tasks beneath the notice of native–born Americans. All this while, like the illegals themselves, she remained largely invisible to those who believed themselves to be in control. Most Holy Death is the real face of the migration, one kept safely off–camera, one never invited to be on the cable talk shows, one worshipped by men and women who scorn presidents.

Across the river in Laredo, a 4,625–bed, $100 million superjail is being built for illegal immigrants. It is part of a jail boom. Twenty years ago, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (formerly INS and now ICE) did not have a single cell in Texas. By 2025, ICE will have 9,250 in Laredo alone. The more Border Patrol agents, the more apprehensions, the more detentions, and the more cells.

Most Holy Death and ICE now face off down by the river.

In America

Esperanza waits tables in Los Angeles. At night she sits and watches a video of her house in Oaxaca. The home has a tile floor, a huge sala. She has never visited this fine residence. Through family she arranged for the design and construction and then they sent her videos for her pleasure. The building is five years old. No one lives in it, and no one may ever live in it. There are similar fine homes popping up in obscure Indian villages across the Mexican south. Their owners cannot afford to visit them because the border crossing has become more difficult and more expensive. But still they pump money into their dreams and sit in various American cities staring at screens displaying their distant shelters.

The case can be made that it is absurd to build a dream house you cannot even visit, much less live in. But that is the nature of dreams — there is always a case to be made against them. This is an éxodo. The people coming north are leaving their villages forever, whether they can admit this fact to themselves or not. As long as resources decline and capital flows dislocate traditional economies, as long as over–population remains a taboo expression, as long as corrupt governments loot the poor, global trade will produce shock waves of migrants. It does not matter if the people in the villages or the officials in the various capitals recognize these facts. The forces on the ground will continue to operate as relentlessly as the hurricanes gestating in the warming oceans. Hardened borders simply deepen this fact until you wind up with a waitress in Los Angeles looking at her dream home in Oaxaca that she cannot afford to visit. Coyotes in Mexico now earn at least $10 billion a year. Expect this to double when Congress adds yet more teeth to the jaws of the border.

The tired and frightened men and women crawling through the line soon become founts of money and wire $340 a month back home on average. This is the largest transfer of wealth to the poor in the history of the Western Hemisphere and it dwarfs all the American gestures of aid and all the revolutions that have filled the plazas of Latin America with tired statues. Remittances to Mexico alone are now estimated to be $20 billion a year, a figure much greater than tourism and rivaled only by the drug trade. (After the U.S. offered migrants amnesty in 1986, families reunited and the motive for remittances ended. Were remittances to dry up today—due to amnesty or a seriously toughened border—the Mexican economy could implode.)

This is also the largest teach–in of American values in history. Some 12 million illegals are studying law enforcement without massive corruption, contract law, the joys of homeownership, the existence of real public schools with real textbooks, the pleasures of freedom of speech and freedom of the press, and recently, in the marches and protests, the strong drug of dissent. Beneath the Mexican and other flags in the demonstrations, a deep shift is taking place as strangers in a new land become part of that new land. American employers have inadvertently created the most affluent and politically active generation of poor people in the history of Latin America. Sending them home would detonate the nations they have come from. The politicians all know that.

I met Miguel in a fashionable bar on South Congress in Austin, a strip for hip tourists who ooze money. I was looking at some photos in a book on Juárez, shots of murders and rapes, when a middle–aged guy sitting next to me said, “That’s my town.” He’d just sold his fine home there, he went on to explain. He’d kept some ranches and things—I felt it wise not to pry—but he was getting out. He thought he’d buy a condo in El Paso for openers. He had two sons in Austin going to college. He was deeply involved in Mexican politics and the names of the elite who run Juárez tripped easily from his lips. One of his family had once sold a ranch to Amado Carrillo–Fuentes, the then–head of the Juárez cartel.

Miguel was part of an invisible flight of middle– and upper–middle–class people who have visas, come across, and then simply do not go home. He said the violence was too much, the economy was too bad, and that there was little hope of change. Like the pollos, he’d made a decision and marched north. But then Miguel was hardly a surprise—the publisher of the Juárez newspaper lives in an El Paso penthouse for safety reasons and also has his children in U.S. universities.

A few days earlier, I was staying at a ranch an hour south of Austin. A local white guy came out to spray the buildings for termites. He’d spent his life in nearby Gonzales, a town of 7,000 where the Texas revolt from Mexico began. He asked me what I was doing there.

I said, “I’m a friend of the owners. I’m down here writing about migrants.”

He looked puzzled for a moment and then asked, “When you say migrants, do you mean wetbacks?”

“Yes.”

“Well, what do you think we should do?”

“You might as well ask me what I think we should do about hurricanes.”

He chewed on that a moment, and then offered, “That’s what I think. Nothing can stop them. I’ve seen guys deported on a Friday and they’re back here at work on Monday.”

In Mexico

The catholic casa del Migrante Nazareth sits on the Nuevo Laredo bank of the Rio Grande. Men can seek refuge here for three days, women sometimes for six. But these days, the Casa is seldom open for the migrants. The woman who answers the door says come back in five hours when a priest will stop by. For blocks near the Casa, men are sprawled on the sidewalks. She looks out at them and explains they are not migrants and so not her concern. Across the Mexican north a silent battle has been taking place between priests influenced by liberation theology and bishops picked by the increasingly conservative Vatican. Here liberation theology seems to be losing.

Or maybe it is because the men who litter the nearby streets are Central Americans. The minute they step into Mexico they become illegal, and so they have been hunted for days and weeks as they have moved toward the line at Laredo, Texas. As in the United States, governments and charities put the needs of their own people—the Mexicans—over those who’ve joined them in the flood north.

The migrants slowly come out of the shadows of the street like ghosts. They are from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador. They refuse to give their names and insist on giving their stories. One Honduran wears a T–shirt that says “Tommy Boy.” He thinks half the population of Honduras has already left. He is New York bound. He believes America is the land of opportunity. “But,” he continues, “it is very hard to reach. I work hard in Honduras, but it is difficult to earn anything. If I go to the U.S., then I can build a home in Honduras. I have spent 30 days getting this far, and this cost me $1,500. I have seen others robbed. I have no money left for a coyote. I will try to cross by myself, but it will not be easy because of la migra. I will do anything. But I know nothing but the fields.”

As the men speak, more gather. They beg for money for food and I fork over $25. A boy in a Yankees cap says, “I usually work construction. I left home a month ago. I am heading for Los Angeles.”

First, he illegally entered Guatemala from Honduras. Then he entered Mexico illegally and boarded the fabled “train of death” where migrants hop freight cars. This part of the trip is very cold, and as a result many cannot hold on to the cars. The boy saw six dead bodies by the tracks. In Empalme Escobedo, Guanajuato, the police appeared on horseback with lariats and roped men around their necks. Some die from this experience. Also, he continues in his soft voice, the taxi drivers are treacherous. They take your money and then dump you by the road in the countryside.

“The U.S.,” he believes, “must be better. I’ll make enough money to build a little house back home. We are all single. There is no money for marriage. If we are sent back to Honduras — no jobs, no money — how can we survive? When I find enough money for water and food, I’ll cross.”

On the wall behind the men, someone has spray–painted BAR HONDURAS.

The Rio Grande is maybe half a block away and lush with trees. On the opposite bank are homes in Texas. From the Bar Honduras, they look like mansions. The men sit and stare out. They face a few problems. The local Mexican police control all the routes down to the river and if you do not pay them, they beat or kill you. There is no work in Nuevo Laredo, so their chances of earning money are close to zero. Coyotes charge $1,600 to $2,000 for passage to San Antonio, 150 miles to the north. Houston costs $300 more. The walk to San Antonio is five to six days.

This information comes from Antonio Canales, a man in his late 30s from Juárez—one of two Mexicans hanging around and eyeing the Central Americans. And he speaks with some authority, as he himself guides groups across, up to 15 people at a time. Thousands cross each day, he says, and there are moments when he’ll see 200 people in the river. More cross at night. Of course, he says, there is a charge for real service, one that delivers you like a suitcase to some distant point in the United States. A Mexican who pays $2,500 to $3,000 will be put up in a cheap hotel and then led across the Rio Grande to the United States and dropped off at any point. A Central American must pay $4,000 to $5,000 for the same service. Those from South America (mainly Peruvians, Bolivians, and Brazilians) must fork over $10,000 to his organization. The business, he rolls on, is controlled by Mexican Americans, and they seem never to be arrested.

As Canales speaks, the Central Americans sit in silence. Some braid cords so that they can secure one–liter water bottles to their wrists. One fishes out a photograph of himself and says, “I am a tailor.” He has an address in Houston and wonders if he can find work there. The air hangs with humidity, the heat is rising, and at times the only sound comes from the buzzing of flies.

The three major Mexican border towns on this stretch of the Rio Grande–Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, and Matamoros–are each pumping 100,000 people a year north, people who have fashioned answers out of things as simple as braided cord.

Luis Angel Ramírez Nevárez, 24, could be a poster child for this can–do attitude. Last year, he left El Salvador and headed north. Somewhere in the Mexican state of Veracruz, he fell off the freight he had hopped, shattered a leg and mangled one arm. His forearm now looks as if the bone had decided to make a sharp turn, reconsidered, and finished up with a U–turn. In January, he arrived in New Orleans because he had heard they needed workers. He did painting and stucco, 10 hours a day, five or six days a week, for 10 bucks an hour. Things were looking up for him even with his mangled limb.

Then, as he walked to his job, he was scooped up by the Border Patrol and pitched back into Mexico. Now he waits for dark. He and a new friend are heading back to New Orleans to occupy the space left by the evacuees.

Everything else is details. The cops who may kill you when you cross, the Border Patrol that will hunt you when you climb out of the river, the five or six days of walking through scrub forest to San Antonio, the passage to New Orleans in a nation where you have no legal standing, all this seems like the flies swirling around the men. Irritants but not real obstacles. In New Orleans, they will earn at least $500 a week. They can be stopped. But not by much shy of death itself.

In America

Five days after katrina made landfall, I walked into an Italian bistro in Houston on Interstate 10. The cluster of surrounding motels had counters piled high with fliers from churches offering aid. The bistro sat 200, and every chair was taken by an evacuee. They were easy to spot with their dazed eyes, disheveled clothing, and sudden fellowship that crossed race and class lines. One black man said he’d spent 18 years as a janitor in a complex near the Superdome. Now he planned to stash the wife in some Houston rental and head back to grab what he saw as fine jobs that would sprout from the soggy ground as reconstruction got under way. But what struck me about the entire scene was the staff toiling in an open kitchen. Except for the hostess and the guy manning the cash register, the entire service crew—cooks, dishwashers, busboys, waiters—were short, dark, Indian–looking people from the Mexican south. I doubt many had papers that were in order. And so I dined amid the constant ringing of cell phones and the constant chatter of evacuees as they were fed by other evacuees from the collapse of a Latin world. One group was helpless; the other group was, probably for the first time, in control of their lives and fortunes.

The migrants started showing up a few weeks later at the Shell station at Lee Circle near the Superdome—one of the many informal hiring halls of a new city. For a few months, there were 300 or 400 a morning, a land–office business in soft drinks and snacks for the gas station. Now it’s down to a hundred or so a day. No one knows how many Latin Americans have swarmed in since Katrina. One estimate guesses at least 100,000 in the Gulf region. Last October, Mayor Ray Nagin complained that his city was being overrun by Mexicans. In the 2000 census New Orleans was 3 percent Hispanic. Now one sees more brown faces than black. But then no one really knows what the current population consists of. It is a work in process, a new kind of place for a new world. And yet some things are the same: When black contractors pull into the Shell station, they seem to hire only the few blacks milling around; white contractors seem to hire only Latinos.

At the Monte de los Olivos Lutheran Church, Pastor Jesus Gonzales ministers to a flock of these newest New Orleanians. He feeds them, helps them find housing, clothes them, offers a clinic (for, among other things, the prevalent Katrina cough resulting from the mold, asbestos, and general filth of demolition work), and teaches them English. Gonzales toiled in the oil fields of west Texas and then felt the need for more meaningful work. His congregation was largely Honduran—refugees from the hurricanes of the ’90s—but is now 60 percent Mexican. When Gonzales walks New Orleans he mainly sees some upscale whites walking big dogs, and Latin Americans. At Mardi Gras this year, he was stunned that half the conversations around him were in Spanish.

His congregants are making $12 to $15 an hour. Their employers keep an eye peeled for the Border Patrol—some have reconfigured their small businesses so that no one can enter without warning. One of his Mexican congregants was assigned an Arabic name by his employer and wears his new identity on a tag. Local Spanish radio issues alerts in code on Border Patrol movements. The coyotes in his church tell him that they’ll take a few months off until the newly assigned National Guard units finish puttering about the border. Gonzales sees no end to the deluge of new migrants so long as there is a need for labor. And right now all the fast–food places are having trouble getting help at $10 an hour.

Out in St. Bernard Parish, destruction was close to total. In the parking lot of the parish’s only open grocery store, Jesse Melendez, a 43–year–old roofing contractor, cuts a deal with a plumber. He’ll get the plumber Mexicans for a finder’s fee of $100 each. Melendez is a wiry man and well decorated with tattoos. He goes to Fort Worth for his illegals, because “there’s a shortage, big time.” Melendez is native born, Puerto Rican in ancestry, feeble in Spanish, and keen on Mexicans. “They bust ass—work hard and consistent.” He pays them twice what he pays blacks. He is convinced the reason St. Bernard Parish is rising from ruin faster than New Orleans is that locals understand the care and feeding of Mexicans. In fact, that’s why the grocery reopened — otherwise contractors had to drive their Mexicans out of the parish to buy food, and while off shopping they might get better offers of work.

The tens of thousands of illegals who’ve poured into the Gulf Coast are but a trickle compared to the numbers who will come if reconstruction is ever seriously undertaken. By early summer, only about 25 schools had reopened in New Orleans. Housing starts are running around zero. And no one of any color or political persuasion thinks the rebuilt levees are worth a damn.

We want an answer, a solution. But there is only this fact: We either find a way to make their world better or they will come to our better world. At the moment, we insist on the wrong answer to the wrong question. And so, the Border Patrol will grow. There will be a wall. Tougher laws will be passed by Congress. And the people will keep coming.