Back during the dotcom boom of the 90s, venture capital funds performed pretty strongly. Since then they’ve pretty much sucked. So what happened? Felix Salmon directs our attention today to a new report from the Kauffman Foundation that addresses this question in considerable detail. The basic answer, I think, comes early on in the report:

Investing in venture capital in the early to mid-1990s generated strong, above-market returns, and performance by any measure was good. What has happened since?….Longtime venture investor Bill Hambrecht notes that, “When you get an above-average return in any class of assets, money floods in until it drives returns down to a normal, and I think that’s what happened.”

Yep. There’s no such thing as an asset class that consistently outperforms the market on a risk-adjusted basis. If it does, money will keep piling in until it doesn’t.

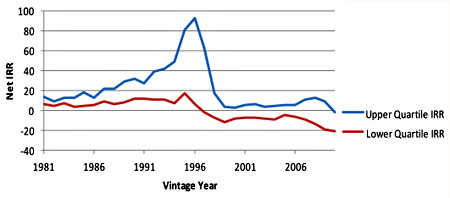

But things are worse than that. According to Kauffman, VC fund returns aren’t just average, they’re lousy. This means that money should be exiting until returns go up. But that’s not happening: “Despite more than a decade of poor returns relative  to publicly traded stocks, however, there appears to be only a modest retrenchment…. We wonder: why are [investors] so committed to investing in VC despite its persistent underperformance?” The chart on the right tells the story. Since 2000, the best performing funds have an internal rate of return that’s only barely positive. The worst funds actively lose money. Taken as a whole, the return on all funds is just about zero. Kauffman says that its VC portfolio hasn’t outperformed the Russell 2000 stock index since 1997.

to publicly traded stocks, however, there appears to be only a modest retrenchment…. We wonder: why are [investors] so committed to investing in VC despite its persistent underperformance?” The chart on the right tells the story. Since 2000, the best performing funds have an internal rate of return that’s only barely positive. The worst funds actively lose money. Taken as a whole, the return on all funds is just about zero. Kauffman says that its VC portfolio hasn’t outperformed the Russell 2000 stock index since 1997.

If you look at the performance of VC funds during the golden years of 1986-1999, it turns out that once you strip out the top-performing 29 funds, the rest — more than 500 — collectively invested $160 billion, and managed to return $85 billion to investors. If you can’t get into one of the best funds — and everybody knows which funds those are — then there’s really no point investing in venture capital at all. But what happens is that some investment board looks at VC returns inclusive of the best funds’ returns, and then mandates a certain investment in VC which assumes they’ll have some kind of access to those top-tier funds. And that’s an extremely dangerous assumption to make, because most of the time it won’t be true.

After looking at the evidence, Kauffman concludes that most VC funds manage their investments not to produce long-term returns, but to provide high returns after about two years, just in time for them to go out for their next round of capital raising. What’s most interesting, though, is that Kauffman doesn’t really blame VC funds for this state of affairs. They blame institutional investors, who (a) put aside preset amounts for VC investment regardless of the state of the market, (b) don’t pay attention to proper investment metrics, (c) have such high turnover that no one is really much interested in long-term returns in the first place, and (d) agree sheeplike to pay fees to VC funds in a way that practically begs them to game the system.

The full report is here. Felix has much more here if you want an abbreviated version. Bottom line: as with everything else, there’s no magic. Nothing outperforms the market automatically, and Wall Street doesn’t care how it makes its money. Generating returns is fine, but keeping suckers on the hook and extracting rents from them is fine too. Caveat emptor.