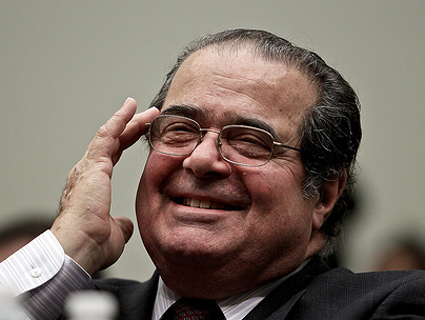

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/stephenmasker/4668514068/sizes/m/in/photostream/" target="_blank">Flickr/The Higgs Boson</a>

Justice Antonin Scalia has changed his mind about a key Supreme Court precedent that supporters of the Affordable Care Act have been using to argue that the law is constitutional. Scalia’s new position leaves little doubt that he’ll vote to overturn the law.

As TPM’s Sahil Kapur notes, a New York Times review of Scalia’s new book describes the Justice arguing that the 1942 Supreme Case Wickard v. Filburn, which featured a broad interpretation of the Commerce Clause that has been key to pro-Obamacare legal arguments, was wrongly decided.

In that 1942 decision, Justice Scalia writes, the Supreme Court “expanded the Commerce Clause beyond all reason” by ruling that “a farmer’s cultivation of wheat for his own consumption affected interstate commerce and thus could be regulated under the Commerce Clause.”

[…]

Justice Scalia’s treatment of the Wickard case had been far more respectful in his judicial writings. In the book’s preface, he explains (referring to himself in the third person) that he “knows that there are some, and fears that there may be many, opinions that he has joined or written over the past 30 years that contradict what is written here.” Some inconsistencies can be explained by respect for precedent, he writes, others “because wisdom has come late.”

Yet Scalia cited Wickard in his 2005 concurrence in Gonzales v. Raich, holding that the Commerce Clause gave Congress the authority to prohibit individuals from growing their own marijuana for medical use. In the opinion, Scalia made an argument often cited by Obamacare supporters in defense of the law, stating that “where Congress has authority to enact a regulation of interstate commerce, it possesses every power needed to make that regulation effective.” In other words, since Congress has the authority to regulate interstate commerce, and health insurance falls into this category, it has the power to implement the individual mandate.

Conservatives were so fearful that the precedent set by Raich would prove insurmountable to their effort to kill Obamacare that Republican-appointed judges developed an argument that would allow the court to avoid overturning Raich, and allow Scalia to avoid contradicting his concurrence. That argument was the much touted “activity/inactivity” distinction, the idea that by taxing Americans who avoid purchasing health insurance Congress was trying to regulate commercial “inactivity” rather than activity. The argument makes little sense, both because the plaintiffs in Raich were not engaging in commercial activity and because health care is something all humans eventually require. But the reasoning nontheless seemed carefully tailored to allow the court to rule against Obamacare without engaging in a potentially embarrassing reversal of their prior rulings. Georgetown University law rofessor Randy Barnett, one of the most influential legal minds among Affordable Care Act opponents, predicted Scalia would adopt this rationale back in December 2010.

Scalia’s explanation of his current views on Wickard shows that the lower court judges needn’t have bothered providing Scalia with an escape hatch. Instead of wisdom “coming late” to Scalia, it may have arrived just in time to justify a vote to overturn the Affordable Care Act.