Photograph by Benjamin Sklar

Photograph by Benjamin Sklar

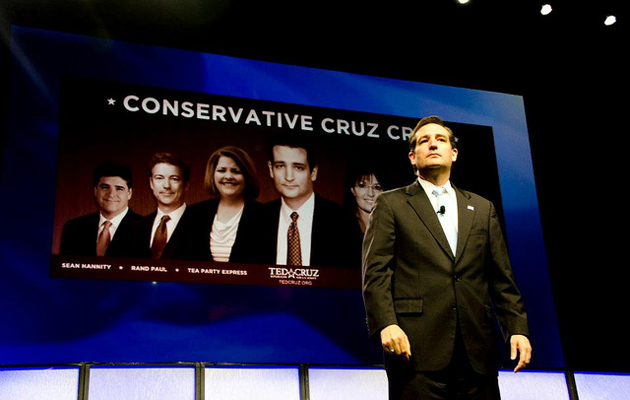

The night he won the runoff, all but guaranteeing he’d be the next Republican senator from Texas, Ted Cruz thanked everyone but the Academy. Speaking to a victory party packed with supporters munching on Chick-fil-A tenders, Cruz spent nine minutes going through the credits—”Dr. Ron Paul”; “our two little beautiful girls!”; “Sarah Palin”—each punctuated by rapturous applause and sheepish, head-bobbing laughter from the candidate. Like any good Texan, he thanked his mother, his father, and the Holy Ghost—”to him be the glory!”—but before he did any of this, he gave a shout-out to one of the conservative icons who had helped forge his political identity. “We should take it as a providential sign that today would be the 100th birthday of Milton Friedman,” Cruz said. “A true champion for liberty, and we are walking in Uncle Milton’s footsteps.”

Victorious candidates don’t typically name-drop Nobel Prize-winning economists from the podium, but Cruz isn’t typical. He’s the thinking man’s tea partier, an intellectual face on a movement and ideology that have long simmered beneath the Republican mainstream. Ask those who know him best for an analogue, and you come back with a very short list. As Robert George, his mentor at Princeton, told Politico, “The closest parallel I can think of is Paul Ryan.”

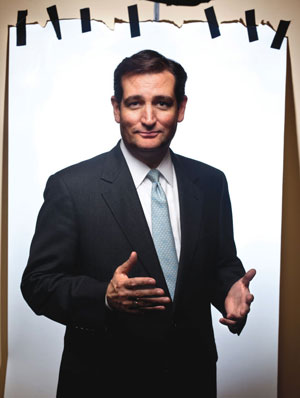

No member of the 113th Congress will arrive in Washington with as much hype as Cruz, who in late July survived one of the most expensive primaries in Texas history to knock off Gov. Rick Perry’s second-in-command, Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst. George Will calls Cruz, the Princeton- and Harvard Law School-educated son of a former Cuban revolutionary, “as good as it gets”; National Review dubbed him “the next great conservative hope,” gushing that “Cruz is to public speaking what Michael Phelps was to swimming.” Political strategist Mark McKinnon channeled the thinking of many in the party when he proclaimed Cruz “the Republican Barack Obama.” He is, with apologies to fellow Cuban American Marco Rubio, the up-and-comer du jour of the conservative movement.

Cruz, who turns 42 in December, represents an amalgam of far-right dogmas—a Paulian distaste for international law; a Huckabee-esque strain of Christian conservatism; and a Perry-like reverence for the 10th Amendment, which he believes grants the states all powers not explicitly outlined in the Constitution while severely curtailing the federal government’s authority to infringe on them. Toss in a dose of Alex P. Keaton and a dash of Cold War nostalgia, and you’ve got a tea party torch carrier the establishment can embrace.

Come January, he’s likely to join an increasingly powerful cadre of ultraconservative Senate Republicans, led by South Carolina’s Jim DeMint and bolstered by freshmen like Rand Paul of Kentucky and Mike Lee of Utah, who are bent on redefining federalism and zapping the government with a shrink ray. They’ll control enough votes to leave a mark on any legislation that passes through the Senate, doing to the upper chamber what Ryan and Eric Cantor did to the lower one: push the body so far right the rest of the caucus will have no choice but to move with it. Put another way: Cruz will aim to make the federal government look a lot more like Texas.

“This is a state that has, more than any other, been the gestational basis for the states versus the feds in the modern era,” says Evan Smith, editor of the Texas Tribune. “This is the state that has some couple dozen lawsuits filed against the federal government. This is the state that has been, more than any other, the Federal Republic of Anti-Obama.” Ted Cruz has been at the heart of all those battles, and now he’s taking the fight to Washington.

Rafael Edward Cruz’s conservative baptism came at 13, when his parents enrolled him in an after-school program in Houston that was run by a local nonprofit called the Free Enterprise Education Center. Its founder was a retired natural gas executive (and onetime vaudeville performer) named Rolland Storey, a jovial septuagenarian whom one former student described as “a Santa Claus of Liberty.”

Storey’s foundation was part of a late-Cold War growth spurt in conservative youth outreach. (Around the same time in Michigan, an Amway-backed group called the Free Enterprise Institute formed a traveling puppet show to teach five-year-olds about the evils of income redistribution.) The goal was to groom a new generation of true believers in the glory of the free market.

Storey lavished his students with books by Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises, political theorist Frédéric Bastiat, and libertarian firebrand Murray Rothbard—and hammered home his teachings with a catechism called the Ten Pillars of Economic Wisdom. (Cruz was a fan of Pillar II: “Everything that government gives to you, it must first take from you.”) Storey’s favorite historian was W. Cleon Skousen, an FBI agent turned Mormon theologian who posited that Anglo-Saxons were descendants of the lost tribe of Israel. Skousen was also a patriarch of the Tenther movement—whose adherents view the 10th Amendment as a firewall against federal encroachment. (By Skousen’s reading, national parks were unconstitutional.)

Cruz was a star pupil. “He was so far head and shoulders above all the other students—frankly, it just wasn’t fair,” says Winston Elliott III, who took over the program after Storey retired. When Storey organized a speech contest on free-market values, Cruz won—four years running. “It was almost as if you wished Ted might be sick one year so that another kid could win.”

Cruz and other promising students were invited to join a traveling troupe called the Constitutional Corroborators. Storey hired a memorization guru from Boston to develop a mnemonic device for the powers specifically granted to Congress in the Constitution. “T-C-C-N-C-C-P-C-C,” for instance, was shorthand for “taxes, credit, commerce, naturalization, coinage, counterfeiting, post office, copyright, courts.” The Corroborators hit the national Rotary Club luncheon circuit, writing selected articles verbatim on easels. They’d close with a quote from Thomas Jefferson: “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free…it expects what never was and never will be.”

From Houston, Cruz moved on to Princeton and then Harvard Law School, a period of his life he refers to, with some seriousness, as “missionary work.” He has said of his time in Cambridge: “The communists on the Harvard faculty are generally not malevolent; they generally were raised in privilege, have never worked very hard in their lives.” He was a believer in a land of Philistines.

While at Princeton, he forged a bond with classmate (and later roommate) David Panton. As a debate team they were unstoppable, setting a university record for the number of awards they won together. A 1992 Princeton Weekly Bulletin article featured the undergrads in oversized sweaters, posing in front of a trophy case filled entirely with their spoils.

But something else happened to Cruz at Princeton: He came under the tutelage of Robert George, the original thinking man’s tea partier. A Catholic political theorist whom the New York Times once dubbed “this country’s most influential conservative Christian thinker,” his big idea is what’s known as “new” natural law. It’s a spin on natural law, a foundational principle best summed up by the Declaration of Independence’s promise that people are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights”—freedoms that are every human’s birthright and that governments must protect. The basic idea behind natural law is that, just as the world is informed by laws of mathematics and physics, so too is it shaped by a set of ethical precepts. George’s theory is that this moral order can be divorced from its theological overtones entirely; even an atheist could grasp it by “invoking no authority beyond the authority of reason itself,” as he puts it.

Applied to politics, however, George’s theories look a lot like classic Christian conservatism. The clearest example is abortion, which George attacks not by citing Scripture, but by arguing that terminating a pregnancy violates the natural order. If abortion contradicts natural law—and natural law is, as George believes, the basis of the Constitution—then it’s not a stretch to argue that the 14th Amendment should grant full citizenship to fetuses.

George met regularly with Cruz and advised him on his senior thesis, an analysis of the history and meaning of the 9th and 10th amendments. They work in tandem: the 9th implies that people have many more rights than are specifically outlined in the Bill of Rights; the 10th reserves unspecified powers for the states. For a growing movement of conservatives, these amendments have taken on an almost religious import as a very real check on the federal government’s power: Delivering the mail and fighting pirates is all well and good, but don’t even think about forcing a sovereign state like Texas to set up a health insurance exchange.

Titled “Clipping the Wings of Angels,” Cruz’s thesis draws its inspiration from a droll passage, attributed to James Madison, in Federalist 51: “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.” The drafters of the Constitution intended to protect the rights of their constituents, Cruz argued, and the last two items in the Bill of Rights offered an explicit bulwark against an all-powerful state. “They simply do so from different directions,” Cruz wrote. “The Tenth stops new powers, and the Ninth fortifies all other rights, or non-powers.” In other words, they sharply delineate the role of the federal government and preserve individual rights—at least those that the states don’t claim the authority to govern. As Cruz saw it, though, his beloved amendments had been trampled by decades of jurisprudence. Government was granting itself powers it couldn’t be trusted to wield; it was playing God with the Constitution.

Cruz’s worldview has remained unflinchingly consistent. Challenged at a Federalist Society panel in 2010 to defend his proposal to convene a constitutional convention to draft new amendments aimed at scaling back federal power, he paraphrased his 21-year-old self: “If one embraces the views of Madison…which is that men are not angels and that elected politicians will almost always seek to expand their power, then the single most effective way to restrain government power is to provide a constraint they can’t change.”

One thing had changed, though, in the two decades since Cruz penned his thesis: His views had started to creep from the fringe to the fore.

Cruz rose fast through the conservative legal ranks. He clerked for Chief Justice William Rehnquist after Harvard Law, advised George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign on domestic policy, and recruited future Chief Justice John Roberts to join the Florida recount brigade. He served under John Ashcroft as an associate deputy attorney general and later returned to Texas, where in 2003 the state’s attorney general, Greg Abbott, appointed him as solicitor general, tasked with handling the state’s appellate cases, including those destined for the Supreme Court. “Ted was an intellectual driving force on all of the issues that we worked on,” Abbott says.

On the campaign trail, Cruz has presented his tenure as solicitor general as the foundation for the work he hopes to do in Washington, on everything from national sovereignty to gay rights.

Most of the cases Cruz argued before the Supreme Court shared a common theme—Texas’ constitutional right to do as it pleases, free from Washington’s meddling.

Of Cruz’s eight oral arguments before the Supreme Court on behalf of Texas, five involved the death penalty, with Cruz arguing, at various points, that Texas should be allowed to execute the mentally ill, a Mexican national who hadn’t been informed of his Vienna Convention right to speak to his consulate, and a man who raped his stepdaughter.

Other cases he took on reflected his conservative Christian ideology. On his campaign website, he touts successfully defending the inclusion of the term “under God” in the Texas Pledge of Allegiance and a Ten Commandments monument on the grounds of the state Capitol. He notes that he fought in the courts to protect a Bible display installed on public property and to have the divorce of a same-sex couple’s civil union invalidated because they’d gotten hitched in Vermont.

No one’s been a bigger promoter of Cruz’s accomplishments than Ted Cruz. Dewhurst’s campaign, tired of hearing its opponent talk about his court cases, charged that Cruz had taken credit for the work of others. The Austin American-Statesman pointed out that he counted a case actually argued by Abbott as one of his own high-court victories. The Washington Post‘s Dana Milbank remembered meeting Cruz during the 2000 presidential campaign and being aggressively pitched on his résumé: “When I mentioned this self-promotional effort to a senior Bush adviser, I received a knowing eye roll in response,” he recalled. Lyle Denniston, who’s covered the high court for five decades and currently writes for SCOTUSblog, says, “Personally, I have found Ted to be very engaging.” But, he adds, “He does love to talk about himself.”

Conservatives hailed Cruz’s primary victory as the dawn of a new era. “Ted’s nomination sent a strong signal that a new conservative Republican Party is being born,” declared Reagan-era New Right stalwart Richard Viguerie.

Cruz’s campaign deployed a brand of Glenn Beck-like Tentherism, warning, among other things, that the United Nations was plotting with George Soros to get the federal government to crack down on golf courses in the name of sustainability. He pledged, à la Ron Paul, to eliminate the departments of education, commerce, and energy, along with the TSA and the IRS. He floated ideas that were unorthodox by traditional GOP standards but pet issues among Federalist Society types, including the use of interstate compacts—an agreement between two or more states—to nullify the individual mandate that is the backbone of health care reform. His theory, drawing on Supreme Court precedent, is that once Congress green-lights such a compact, it will supersede whatever federal law is in place, acting as a backdoor veto.

Cruz’s ideas did not catch on at first. In May, he lost his initial primary—badly—to Dewhurst. But with the vote spread out among four main candidates, Dewhurst, who had poured nearly $20 million of his personal fortune into the campaign, came a few points short of the majority needed to win the nomination outright. Which meant that Cruz and Dewhurst headed to a runoff, where turnout was 21 percent lower. Cruz’s victory—by 14 points—was made possible by a small cohort of die-hard activists, a last-minute flood of outside support and money from groups like Dick Armey’s FreedomWorks and its super-PAC, and a flurry of barnstorming by national conservatives, including Rand Paul, Jim DeMint, and Sarah Palin.

Cruz ran as an outsider, even though his credentials—Harvard Law Review, Rehnquist court, Bush campaign, Perry administration—did not fit that billing. But, schooled since childhood in its tenets, he spoke the language of the tea party fluently. And those same credentials gave establishment Republicans hope; after his runoff win, RedState‘s Erick Erickson, an early booster, warned that the Republican establishment was making “near sexual advances” toward Cruz, intent on coaxing him to their side. Cruz’s greatest asset is that he lives in both worlds.

Last October, at the Family Research Council’s Values Voter Summit in Washington, Cruz brought down the house with a story about his father’s appearance at a Texas tea party rally. At that event, Rafael Cruz, a programmer turned pastor, had launched into a lengthy discourse on an inspirational young leader who’d come to power on a message of hope and change. “He never once mentioned the words ‘Barack Obama’; he simply described what Fidel Castro did,” Ted Cruz said. Ted’s style bore all the trappings of a polished debater, everything scripted down to the hand gesture. He clasped and unclasped his hands and, for emphasis, brought them crashing down like a concert pianist. “Now what does it say about you that you hear what Castro did and you think immediately that it must be Barack Obama?”

During the opening night of the Republican convention in August, Cruz regaled the sea of delegates with “a love story of freedom” and again gave a shout-out to his dad, whose story has featured prominently in the campaign.

“When he came to America, él no tenía nada, pero tenía corazón,” Cruz said, breaking into Spanish (a language he doesn’t speak fluently). “He had nothing, but he had heart. A heart for freedom.”

The following night, I came across Rafael Cruz on the floor of the Tampa Bay Times Forum. He had come down from the VIP seats to watch Paul Ryan accept his party’s vice presidential nomination with the Texas delegation, a lone head of thinning white hair in a crowd of matching cowboy hats and Lone Star shirts. Ted Cruz, through his aides, had declined my repeated requests for an interview, so I thought I’d try my luck with his father, a onetime pro-Castro revolutionary who had been jailed and tortured in Cuba for revolting against the repressive regime of Fulgencio Batista. He had later grown disillusioned with the authoritarian ways of the new Cuban leader he’d helped to empower.

Over the pounding beat of the convention hall band, the elder Cruz reflected on how he’d first nudged his son to the right by talking up Ronald Reagan at the dinner table and driving him to Houston to work with Rolland Storey. “Instead of reading comic books, he was reading Adam Smith, he was reading Milton Friedman, he was reading von Mises, he was reading Frédéric Bastiat,” he told me. “I would tell him, ‘You know, when I lost my freedom in Cuba I had a place to come to. We lose our freedoms here, where are we going to go?'”

Two decades after the end of the Cold War, Cruz the elder’s tales of Batista and the false promise of Castro may feel like they belong in a time capsule. But Ted Cruz has picked up the torch. For all the talk of Cruz as the GOP candidate of the future, there’s something anachronistic in what he’s selling. The 10th Amendment theories he espouses have cropped up time and again—most prominently, perhaps, during the civil rights clashes of the 1950s and ’60s, when Southern governors touted their (nonexistent) right to invalidate federal laws. His social conservatism harkens back to the ’90s, when the gay rights agenda (which Cruz has pledged to combat in DC) was seen lurking around every corner. His fear of international treaties as a gateway to the dissolution of American sovereignty might have fit right in during the Eisenhower era—or in the pages of the Ron Paul newsletters that Storey kept on hand for his conservative pupils to browse. What’s different is that Cruz has backup, what DeMint calls a “critical mass” of Republican lawmakers who share the same vision—one that has been straining for decades to break through.

As Cruz entranced the Values Voter crowd with the story of a man and a message that seemed frozen in time, he might as well have been talking about himself, a forward-thinker and a throwback, as much the party’s future as he is a brightly burning ember of its past.