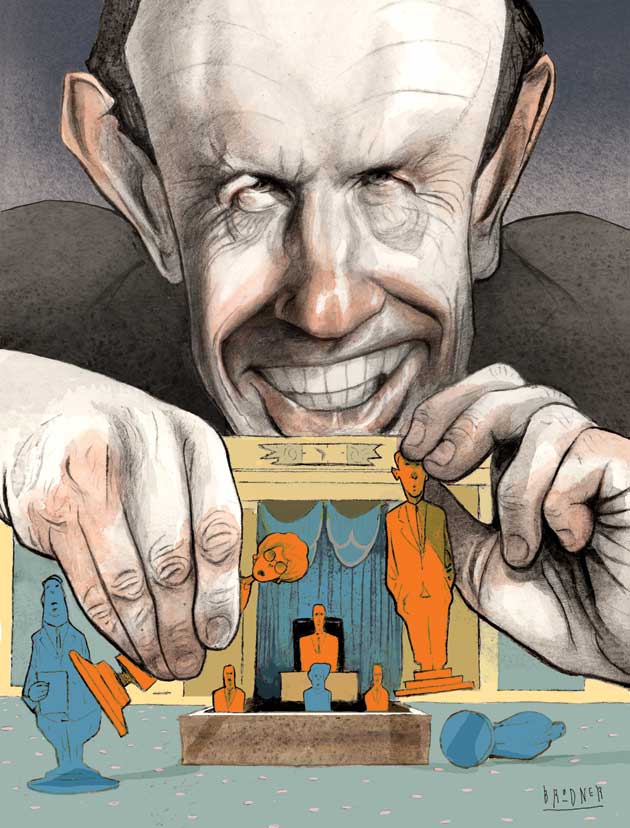

Illustration by Steve Brodner

IN THE PREDAWN TWILIGHT of December 4, 2012, Randy Richardville, the Republican majority leader of the Michigan Senate, called an old friend to deliver some grim news. Richardville’s two-hour commute to the state capitol in Lansing gave him plenty of time to check in with friends, staff, and colleagues, who were accustomed to his early morning calls. None more so than Mike Jackson.

Jackson and Richardville had grown up in the auto town of Monroe, 40 miles south of Detroit. Jackson now headed Michigan’s 14,000-member carpenters and millwrights’ union, which had endorsed Richardville, a moderate Republican, for 10 of the 12 years he’d served in the state Legislature.

“Guess where I was last night,” Richardville said.

Jackson wasn’t in a guessing mood—and it wasn’t just the early hour. Since the election a few weeks earlier, Republicans had been aiming to use the current lame-duck session to ram through a controversial piece of legislation known as right-to-work. Such laws, already on the books in 23 states, outlawed contracts requiring all employees in a unionized workplace to pay dues for union representation. Jackson and other labor leaders were scrambling to head off the bill, widely regarded as a disaster for unions. Richardville, who had once told a hotel conference room filled with union members that right-to-work would pass “over my dead body,” was one of the votes they’d counted on.

Richardville said he’d spent the previous evening at a fundraiser in western Michigan. At one point during the event, he was escorted into a private room where a dozen wealthy business moguls were waiting for him. Some he recognized as heavy hitters in Michigan politics; others had flown in from out of state.

One of the men in the room glared at Richardville. “You gotta grow a set and move this legislation,” the man said, referring to right-to-work. Had he ever run for office? Richardville asked. The man said no. “Well, when you grow a set and give that a try,” Richardville snapped, “then you can talk about the size of my testicles.”

Jackson was wide awake now. “Good for you,” he said. “How’d it end?”

“Mike, you’re fucked,” Richardville said. “They’ve got all the money they need, they’re going up on the air, and they’re going to push this freedom-to-work thing.”

Wasn’t there some way to head off the bill? Jackson asked. “They’ve got my caucus,” Richardville replied. “You can’t imagine the pressure I’m under.”

The pressure came largely from one man present at that fundraiser: Richard “Dick” DeVos Jr. The 58-year-old scion of the Amway Corporation, DeVos had arm-twisted Richardville repeatedly to support right-to-work. After six years of biding their time, DeVos and his allies believed the 2012 lame duck was the time to strike. They had formulated a single, all-encompassing strategy: They had a fusillade of TV, radio, and internet ads in the works. They’d crafted 15 pages of talking points to circulate to Republican lawmakers. They had even reserved the lawn around the state capitol for a month to keep protesters at bay.

A week after Richardville’s early morning call to Jackson, it was all over. With a stroke of his pen on December 11, Gov. Rick Snyder—who’d previously said right-to-work was not a priority of his—now made Michigan the 24th state to enact it. The governor marked the occasion by reciting, nearly verbatim, talking points that DeVos and his allies had distributed. “Freedom-to-work,” he said, is “pro-worker and pro-Michigan.”

THE DEVOSES sit alongside the Kochs, the Bradleys, and the Coorses as founding families of the modern conservative movement. Since 1970, DeVos family members have invested at least $200 million in a host of right-wing causes—think tanks, media outlets, political committees, evangelical outfits, and a string of advocacy groups. They have helped fund nearly every prominent Republican running for national office and underwritten a laundry list of conservative campaigns on issues ranging from charter schools and vouchers to anti-gay-marriage and anti-tax ballot measures. “There’s not a Republican president or presidential candidate in the last 50 years who hasn’t known the DeVoses,” says Saul Anuzis, a former chairman of the Michigan Republican Party.

Nowhere has the family made its presence felt as it has in Michigan, where it has given more than $44 million to the state party, GOP legislative committees, and Republican candidates since 1997. “It’s been a generational commitment,” Anuzis notes. “I can’t start to even think of who would’ve filled the void without the DeVoses there.”

The family fortune flows from 87-year-old Richard DeVos Sr. The son of poor Dutch immigrants, he cofounded the multilevel-marketing giant Amway with Jay Van Andel, a high school pal, in 1959. Five decades later, the company now sells $11 billion a year worth of cosmetics, vitamin supplements, kitchenware, air fresheners, and other household products. Amway has earned DeVos Sr. at least $6 billion; in 1991, he expanded his empire by buying the NBA’s Orlando Magic. The Koch brothers can usually expect Richard and his wife, Helen, to attend their biannual donor meetings. He is a lifelong Christian conservative and crusader for free markets and small government, values he passed down to his four children.

Today, his eldest son, Dick, is the face of the DeVos political dynasty. Like his father, Dick sees organized labor as an enemy of freedom and union leaders as violent thugs who have “an almost pathological obsession with power.” But while DeVos Sr. simply inveighed against unions, Dick took the fight to them directly, orchestrating a major defeat for the unions in the cradle of the modern labor movement.

Passing right-to-work in Michigan was more than a policy victory. It was a major score for Republicans who have long sought to weaken the Democratic Party by attacking its sources of funding and organizing muscle. “Michigan big labor literally controls one of the major political parties,” Dick DeVos said last January. “I’m not suggesting they have influence; I’m saying they hold total dominance, command, and control.” So DeVos and his allies hit labor—and the Democratic Party—where it hurt: their bank accounts. By attacking their opponents’ revenue stream, they could help put Michigan into play for the GOP heading into the 2016 presidential race—as it was more than three decades earlier, when the state’s Reagan Democrats were key to winning the White House.

More broadly, the Michigan fight has given hope—and a road map—to conservatives across the country working to cripple organized labor and defund the left. Whereas party activists had for years viewed right-to-work as a pipe dream, a determined and very wealthy family, putting in place all the elements of a classic political campaign, was able to move the needle in a matter of months. “Michigan is Stalingrad, man,” one prominent conservative activist told me. “It’s where the battle will be won or lost.”

STEP OFF THE JET BRIDGE at the Gerald R. Ford International Airport in Grand Rapids, and the DeVos imprimatur is everywhere. Leaving the airport you pass the West Michigan Aviation Academy, a charter school founded by Dick DeVos in 2010. In Grand Rapids itself, there’s the DeVos Place convention center, the DeVos Performance Hall, the DeVos Graduate School of Management, the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, the Richard and Helen DeVos Center for Arts and Worship, the DeVos Communication Center at Calvin College, and the DeVos parking lot at Grand Valley State University.

I grew up not far from Grand Rapids, and the DeVos name was never far from mind. I heard it on the radio and at the dinner table—my parents are both teachers, and the DeVoses’ education reform efforts were a topic of discussion. In western Michigan, the DeVoses were the closest thing we had to Carnegies or Rockefellers.

Populated by the descendants of devout Dutch immigrants, Grand Rapids is a deeply Christian enclave that locals call “GRusalem.” Once a city of furniture makers, Grand Rapids began to prosper in the 1970s and 1980s, thanks largely to Amway. Launched in an abandoned gas station, the company grew into an empire by enlisting an army of “independent business owners,” or IBOs, to peddle Amway’s wares, eventually expanding to more than 100 countries and territories. The company formulated the business model now used by the likes of Mary Kay, Avon, and Herbalife, in which salespeople earn money by recruiting others into the business. In 1975, the Federal Trade Commission accused Amway of operating a pyramid scheme, but after a years-long investigation the agency rescinded the charge.

From the start, DeVos and Van Andel infused Amway—short for “American Way”—with their Christian beliefs and free-market principles. The Institute for Free Enterprise, a think tank run out of Amway’s headquarters, organized workshops nationwide to help teachers incorporate free-market economics into their lesson plans. During the 1970s, Amway bought ads in major newspapers that railed against taxation and regulation. Together, DeVos and Van Andel also helped to launch the now-defunct Citizen’s Choice, a conservative counterweight to the good-government group Common Cause. A smattering of headlines in the centerfold of Amway’s 1980 corporate magazine captures the company’s institutional philosophy: “Entrepreneur DeVos Preaches Self-Help: GOVERNMENT MEDDLING ASSAILED.” “Taxes and Government Rules Destroying Free Enterprise—Van Andel.”

Amway’s success and its conservative ethos catapulted both the elder DeVos and Van Andel into the highest reaches of Republican politics. Van Andel, who died in 2004, chaired the US Chamber of Commerce in 1979 and 1980, and he gave millions to Republican and conservative organizations in his lifetime. DeVos, meanwhile, was an early member and funder of the Council for National Policy, a secretive network of hardline conservative leaders founded by Left Behind author Tim LaHaye. Ahead of the 1980 elections, Ronald Reagan personally asked DeVos to lead the GOP’s national fundraising efforts. Short on cash and reeling from Jimmy Carter’s election and the aftershocks of the Watergate scandal, the party needed all the help it could get. As the Republican National Committee’s finance chairman, DeVos raised $46.5 million ($132 million in today’s dollars).

He fit the part of GOP rainmaker-in-chief, wearing a diamond pinkie ring and Gucci loafers, driving a Rolls-Royce, and frequently commuting to his nearby office by helicopter. He once docked Amway’s $5 million yacht on the Potomac River in Washington to hold court with Michigan’s congressional delegation, RNC staffers, and personnel from 12 embassies representing countries where Amway did business. DeVos was also a strident voice within the party: In an era when Republicans still courted labor, he urged the GOP to ignore union members. “If they want to be represented by somebody else,” he once said, “good for them.” At a party meeting in 1982, he called the recession that was spiking inflation and unemployment “beneficial” and “a cleansing tonic” for society.

The RNC canned him soon after, but that didn’t stop DeVos and his clan from steering hundreds of thousands of dollars into Reagan’s 1984 reelection effort and George H.W. Bush’s 1988 campaign. On the eve of the 1994 elections, Amway made a $2.5 million soft money contribution to the Republican Party; it was the largest corporate donation ever recorded. Amway also galvanized its 500,000-plus sales force into a massive political network, drumming up hundreds of thousands of dollars in contributions for favored candidates like Rep. Sue Myrick (R-N.C.), a former Amway saleswoman and the first female chair of the ultraconservative Republican Study Committee.

In late 1992, Dick succeeded his father as the president and CEO of Amway, aggressively expanding the company into Asian markets like China and Korea, which produce much of Amway’s profits today. His wife, Betsy, an heiress to a Michigan auto parts fortune, hailed from a conservative dynasty of her own; her father, Edgar Prince, was a founder of the Family Research Council. (Betsy’s brother is Erik Prince, the ex-Navy SEAL who founded the infamous private security company Blackwater.) Together, Dick and Betsy formed Michigan’s new Republican power couple.

Betsy, who is 56, is the political junkie in the relationship. She got her start in politics as a “scatter-blitzer” for Gerald Ford’s 1976 presidential campaign, which bused eager young volunteers to various cities so they could blanket them with campaign flyers. In the ’80s and ’90s, Betsy climbed the party ranks to become a Republican National Committeewoman, chair numerous US House and Senate campaigns in Michigan, lead statewide party fundraising, and serve two terms as chair of the Michigan Republican Party. In 2003, she returned at the request of the Bush White House to dig the party out of $1.2 million in debt. A major proponent of education reform, Betsy serves on the boards of the American Federation for Children, a leading advocate of school vouchers, and Jeb Bush’s Foundation for Excellence in Education, which supports online schools.

Through the ’70s and ’80s Dick worked his way up at Amway and, like his father, rose to prominence within GOP circles thanks to his prodigious fundraising, generous political contributions, and his perch atop the family’s multibillion-dollar company. In 1998, he launched a PAC called Restoring the American Dream, which then-House Majority Leader (and former Amway salesman) Tom DeLay credited with playing “an essential role” in preserving GOP control of the House in 1998 and 2000. DeLay, Myrick, and three other House Republicans who had been Amway salespeople created an informal “Amway caucus.”

The DeVos name carried plenty of weight in Washington, but the clan loomed especially large in Michigan, and had opportunities to exert its influence in ways big and small. Once, Betsy complained to her hometown newspaper, the Grand Rapids Press, after an April 2004 story reported that she had blamed “high wages” for Michigan’s economic woes—a comment that touched off a statewide controversy. As unhappy as she was, there wasn’t much chance she’d been misquoted: The reporter had taken the language out of an official Michigan GOP press release and had even given Betsy a chance to respond to her own words. Mike Lloyd, then the Press‘ editor, says that while he doesn’t recall the details of DeVos’ grievance, it’s likely he heard her out. Ultimately, the paper ran an unusual mea culpa saying the article had “oversimplified” the remarks while “distorting her original meaning.” (In general, Lloyd denies the family ever used its “economic muscle…to attempt to influence or change” the paper’s coverage.)

Mike Pumford knows what it’s like to be on the wrong side of the DeVoses. A former high school teacher and public school administrator, he was elected to the state House in 1998 as a moderate Republican, and he publicly opposed Dick and Betsy’s push to expand charter schools and introduce school vouchers. (In 2000, Dick and Betsy helped underwrite a ballot initiative to expand the use of vouchers and lost badly.)

When Pumford ran for reelection in 2002, a DeVos-funded group called the Great Lakes Education Project blanketed his rural district with glossy flyers calling him a puppet of the Michigan Education Association and a “tax-and-spend Republican” for backing an increase in cigarette taxes. “They just kicked my ass in that election,” he says. And though he eked out a victory, the DeVoses got the final word. When Pumford asked for the chairmanship of the subcommittee overseeing public education funding, he says, then-House Speaker Rick Johnson told him there was “no way in hell we can give it to you.” Why? It would piss off the DeVoses. (Johnson did not respond to requests for comment.)

In 2004, Pumford quit politics in disgust. “I spent a lot of time fighting bullies,” he told me. “Kids tend to bully with their mouths and fists. Billionaires tend to bully with their pocketbooks.”

FOR DICK DEVOS, the fight over right-to-work started with a humbling defeat. In 2006, he ran for governor of Michigan, spending $35 million of family money—the most ever spent on a gubernatorial campaign in the state—only to be routed by incumbent Jennifer Granholm. His timing was terrible: Thanks to Iraq War weariness and a series of GOP scandals, not one Republican beat an incumbent Democrat in a congressional or gubernatorial race anywhere in America that year. Postelection, DeVos turned down offers to run the state party and ducked out of the political limelight to ponder his next move.

The following year, he and a close ally, Ron Weiser, whose prolific fundraising had earned him the US ambassadorship to Slovakia under George W. Bush, hired Republican pollster Bill McInturff to gauge Michiganders’ views on a range of issues. According to Weiser, McInturff came back with a surprising result—his polls showed nearly 70 percent support for right-to-work. DeVos and Weiser shared their findings with donors and operatives statewide, quietly brainstorming about how to capitalize on those numbers.

Despite declining membership, nearly 20 percent of Michigan’s workforce belonged to unions and, as in other union-heavy states, right-to-work had long been a right-wing fantasy. For decades, the lone voice on the issue was the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a state-level think tank founded in 1987 to spread free-market ideas and antagonize the unions. (In a June 2011 email obtained by Progress Michigan, a Mackinac Center staffer told a state lawmaker: “Our goal is [to] outlaw government collective bargaining in Michigan, which in practical terms means no more MEA.”) The DeVoses are among the center’s biggest financial backers, and Dick served on its board of directors. Still, despite a flurry of policy briefs and op-eds produced by the Mackinac Center, the issue remained a nonstarter. “We never had the sense that the votes were there to get it done,” John Engler, the former governor, told the National Review in 2012. “A lot of Republicans weren’t ready to deal with the issue. Labor was too strong.”

Studying McInturff’s polling numbers, DeVos and Weiser saw a shift in the political winds. Early in 2008, they dined in Washington, DC, with former Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating, who in 2001 became the first governor in nearly a decade to sign a right-to-work bill into law. He knew just how fierce the fight could be. Keating advised DeVos and Weiser to hold off on right-to-work until they’d elected a Republican governor and, ideally, taken full control of the Legislature. (Democrats controlled the state House at the time.) “That resonated hugely with Dick,” says one friend. “He said, ‘I’m for this, but until we have a governor who’s going to champion it, we need to bide our time.’ So it went on the shelf.”

In 2009, with DeVos’ help, Weiser was elected as the state GOP chair, and he led the party to a landslide in 2010, winning every state-level race. But the new Republican governor, Rick Snyder, resisted right-to-work, saying repeatedly it was “not on my agenda.” Watching his fellow Class of ’10 governors—especially Scott Walker in neighboring Wisconsin—clash with organized labor dampened Snyder’s enthusiasm for the “very divisive” issue.

But some of the Legislature’s Republican members wanted this fight. A small but vocal group of them had campaigned on right-to-work and agitated for the issue as soon as the 2011-12 session convened. “It was kind of like the kid on the way to Disney World saying, ‘Are we there yet? Are we there yet?'” recalled Republican state Sen. Patrick Colbeck.

As the chorus grew louder, the unions decided to launch a preemptive strike. In July 2012, they got an amendment on the ballot that would enshrine collective bargaining rights in the state constitution. Known as Proposition 2, the ballot measure sent labor’s enemies into overdrive. “The minute that thing got on the ballot, we knew we needed to mobilize quickly,” says Greg McNeilly, Dick and Betsy’s longtime political adviser.

That summer, a group of GOP lawmakers and business leaders—McNeilly won’t say who—asked DeVos and Weiser (who served as finance chairman for the Republican National Committee in 2012) to lead the charge to defeat Proposition 2. They gladly took on the job—DeVos called Prop. 2 “a head-shot at Michigan’s recovery”—but they had bigger things in mind: With McNeilly, who managed the anti-Prop. 2 campaign, DeVos and Weiser sketched out a strategy to defeat the measure, then use the political momentum to pass right-to-work immediately afterward. They also strategized about every other possible obstacle: defending the law from a possible legal challenge, beating a constitutional amendment to repeal it, and protecting Republican lawmakers from recall elections.

They began the anti-Prop. 2 effort in September. Polls showed that 60 percent of voters supported the measure, but DeVos and Weiser tapped their national donor networks, hauling in millions from Las Vegas gambling tycoon Sheldon Adelson, Texas investor Harold Simmons, and a slew of Michigan business groups. Ten DeVos family members pitched in with a combined $2 million. The DeVos-backed campaign ran hundreds of ads in the two months before the vote, claiming the measure would give unions far too much power, cost the state more than $1.6 billion, and imperil student safety by making it impossible to fire negligent teachers.

By Election Day, the two sides had spent a total of $47 million, making it the most expensive ballot measure in Michigan history. Voters defeated Prop. 2 by a 15-point margin. DeVos and Weiser wasted no time moving to the next phase of their plan.

DESPITE THE DEFEAT of Prop. 2, the unions believed all was not lost. Most Republican lawmakers seemed to have no stomach for another battle with organized labor. Days after the November elections, Mike Jackson, the carpenters’ union head, dined in Lansing with a handful of Republican state senators who assured him they didn’t support right-to-work. Other Republicans worried that a right-to-work push could lead to recalls. “At the time, I thought it was the dumbest thing we could’ve done politically,” says one GOP legislative aide.

In public, Snyder insisted that right-to-work was still not on his agenda. Privately, his aides met with labor and suggested that concessions on other issues would keep the bill off the table. All the while, though, DeVos and his team were furiously whipping the vote. In the weeks before the start of the lame-duck session, DeVos personally called dozens of state lawmakers, pledging his support if the unions threatened recalls or primary challenges.

A week before the lame duck began, on November 20, 2012, DeVos and Weiser met with members of the Republican leadership, business bigwigs, and the top legislative aide to Gov. Snyder to pitch their plan. Snyder and the GOP leadership were still queasy, fearing a Wisconsin-style revolt; where the protesters in Madison had ultimately failed, in Michigan, a labor stronghold, they just might prevail. “There was all this hemming and hawing,” says one attendee.

“What do you guys need to hear?” DeVos asked. “What can we do to help?”

A plan, came the reply. A plan showing that they wouldn’t be committing political suicide.

McNeilly, DeVos’ political adviser, took the floor. He had recently formed a nonprofit group called the Michigan Freedom Fund. It planned to raise millions from the DeVos family and other donors. McNeilly’s pollster was testing DeVos’ “freedom-to-work” message statewide. And the group was plotting a statewide ad blitz to give air cover to Republican lawmakers. By the time McNeilly finished talking, the mood in the room had shifted from apprehensive to optimistic. “Sitting around that table we felt like a rag-tag grouping of Davids, in the historic Biblical story,” DeVos told me in an email. “But we left the table committed to doing our best to change Michigan’s future for the better.”

By now it was down to a few Republicans on the fence, and the heavy artillery came in. According to labor lobbyists and House and Senate Republican staffers, several undecided GOP lawmakers received threats of primary challenges from Team DeVos if they opposed right-to-work. One House Republican told me that Weiser called him up to suggest he’d have difficulties in the future if he voted no. The message, according to another wavering lawmaker’s aide, was clear: “We will run you out of town.”

In early December, the Michigan Freedom Fund unleashed its freedom-to-work ad campaign. The group also enlisted GOP pollster and communications guru Frank Luntz to help craft a message “bible” that was distributed to every Republican state lawmaker for use during the right-to-work push; it included prepackaged answers to potential questions from constituents and reporters. (“Q. Isn’t this really just about trying to break unions? A. Freedom-to-work is about restoring workplace fairness and equality, not curtailing unions.”) The Freedom Fund even brought Luntz to Lansing to rally lawmakers. This is your chance to make history, Luntz exhorted them. It’s now or never.

On December 6, Snyder shocked the state by announcing that lawmakers would vote on right-to-work that day and that he would sign the legislation when it got to his desk. DeVos worked the phones all the way to the end, even calling several lawmakers on their cellphones as they prepared to cast their votes.

The state legislators who led the right-to-work fight say it was the strategy crafted by DeVos and his allies that convinced hesitant Republicans, not least of them the governor himself, to pull off what DeVos called “the largest shift in public policy in Michigan in a generation.”

“[Snyder] needed to see the win plan,” recalled Rep. Mike Shirkey—it was what swayed him from “‘not on my agenda right now’ to ‘it just moved to the agenda.'”

IN LATE SEPTEMBER 2013, hundreds of Republican lawmakers, political operatives, and activists gathered at picturesque Mackinac Island in northern Michigan for the state party’s biannual leadership conference. The gathering is always held at the Grand Hotel, an extravagant, 126-year-old landmark with sweeping views of Lake Huron. The 2013 guest list was packed with prominent names and 2016 hopefuls: Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, and Karl Rove all had keynote speaking slots.

One of the main attractions was a Saturday morning panel on the right-to-work victory. The panelists included DeVos adviser Greg McNeilly and two Republican lawmakers who were instrumental in the bill’s passage. Dick and Betsy DeVos watched from the front row.

State Sen. Patrick Colbeck told the crowd that he’d spoken with allies in Illinois, Missouri, and New Hampshire who were interested in passing right-to-work bills of their own. But, he added, conservatives in those states were waiting to see if Michigan Republicans could hold on to their law—and their majority—in 2014. “If we demonstrate that we can defend the high ground, just like Gov. Scott Walker did in Wisconsin, you give courage pills to every state legislator and every state legislature across the country.”

“This is the election that seals the deal,” said McNeilly. With a GOP victory, “freedom-to-work becomes the new norm.”

DeVos and his allies had long since started working toward that goal. Their Michigan Freedom Fund is now a conglomerate of political vehicles, including a charitable foundation, a 501(c)(4) advocacy group, and a 527 political committee. “We’re not the Chamber of Commerce; we’re not the Republican Party,” he says. The groups, McNeilly notes, will steer clear of social issues like abortion and gay rights, and instead promote a “freedom agenda” of lowering taxes, slashing regulations, and privatizing public education. The fund will recruit and groom candidates and campaign to send those politicians to Lansing.

The ambitious project is more than a state-level power play: DeVos is part of a wave of superwealthy political activists—think the Koch brothers on the right, the billionaire environmentalist Tom Steyer on the left—who are operating outside the traditional party system. They are financing their own political infrastructure and setting their own agenda.

And it seems to be working. By pulling off the unthinkable, DeVos and his allies have emboldened conservatives around the country to go on the offensive. Following the passage of right-to-work, DeVos has opened his playbook to lawmakers, activists, and donors nationwide who are interested in following Michigan’s lead. “As is often the case in politics generally, timing is critical,” DeVos told me. “So the lesson to others is: Be prepared. Invest in the infrastructure necessary to leverage an opportunity when it presents itself.” He says other conservatives “are hoping for an opportunity to bring freedom-to-work to their home states” and “have voiced their appreciation for the example Michigan provided.” As he told an audience at the annual conference of the conservative State Policy Network in September, “If we can do it in Michigan, you can do it anywhere.”