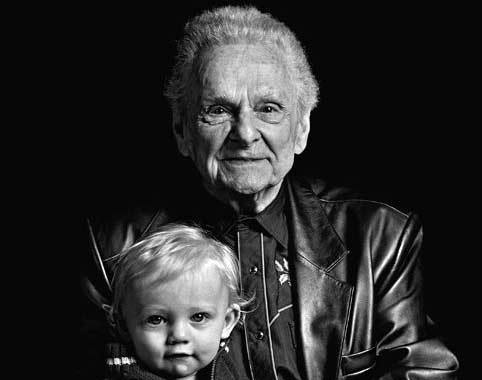

Ralph Stanley with grandson; photo by <a href="http://www.barnwellphoto.com" target="_blank">Tim Barnwell</a>

Q. How many Stanley Brothers does it take to screw in a lightbulb?

A. Two. Carter Stanley to do it, and Ralph Stanley to talk about how much better the old bulb was.

That’s a joke I usually apply to Vermonters, but it aptly captures one side of renowned old-time crooner Ralph Stanley, whose memoir, Man of Constant Sorrow: My Life and Times, is out this week on Gotham Books. A recurring theme—the book is first person, as told to music writer Eddie Dean—involves a time when fellow musicians on the struggling bluegrass circuit were changing their acts to suit modern audiences and compete with rock and roll. Stanley wouldn’t budge. He won’t even call his music “bluegrass”—despite his close friendship with Kentucky’s late Bill Monroe, the country music pioneer from whom the term originated (Kentucky being the bluegrass state). Sure, Stanley admires those fast pickers (like Monroe, Ricky Skaggs, Lester Flatt, and Earl Scruggs), but he’ll just tell you he plays hillbilly music. He prefers the old lightbulb.

Little surprise, given his upbringing in the remote mountain towns of Dickenson County, Virginia—where he was “borned” and still lives at age 82. “There were no books I can recall, save for the family Bible,” he says of the home place. “There wasn’t much in the way of toys and playthings like children have today. My parents wouldn’t allow even a deck of playing cards in the house, because it could lead to gambling and all kinds of trouble. For Christmas, we’d get an orange, one for Carter and one for me, and a handful of rock candy. Maybe a cap-gun, too. It wasn’t ’til years later that I got a bicycle of my own and I had to trade a dog to get that bike.”

One of the family’s few modern conveniences, as Ralph puts it, was a wind-up Victrola, which the boys would use to wear out stacks of 78 rpm records from groups like the seminal Carter Family, Grayson & Whitter, and Fiddlin’ Powers and Family. There was a radio, too, which picked up Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry. The boys fell in love with acts like Roy Acuff, Charlie and Bill Monroe, the Delmore Brothers, Uncle Dave Macon, and Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith. They also got a taste for traditional tunes from their father, Lee Stanley, who liked to sing old songs like “I’m a Man of Constant Sorrow,” “Pretty Polly,” “Wild Bill Jones,” and “Omie Wise.”

The Stanleys didn’t have much money. Nobody in those mountains did. What they did have were musical genes, a stubborn willfulness, and a shared legacy of sorrow. Lucy Smith, one of 11 siblings—all of whom played musical instruments—was 38 years old and already twice widowed when she married Lee Stanley, a widower himself. Her first loss was her teenage sweetheart and fiancé, who died in a mining accident. A decade later she remarried, only to have her new husband succumb to a brain tumor two years later. Somewhere in the bargain, she gave birth to a daughter, Ruby. Lee brought three boys and three girls to the marriage, but because the half-siblings were so much older than Carter and Ralph, the brothers were pretty much raised on their own. “My dad’s first wife died and I never did know what of, because my dad never did say and I never did ask,” Ralph recalls.

He wouldn’t have, either. Ralph was like that. Carter, two years his senior, was the gregarious one—a charming, born-salesman type. Ralph, shy and awkward, kept a low profile. “It was hard work getting Dr. Ralph to open up, as he is not talkative or introspective by nature and his age was a factor as well,” coauthor Dean tells me via email. “Like, he told me last time I spoke with him for the acknowledgements section, ‘I want to thank you Eddie, for aggravating me for the last two and a half years.’ He was only half-joking.”

That “doctor” title might seem a stretch for a man who was never one for book learning and never attended college. But oddly enough, the younger Stanley took to the title after receiving an honorary doctorate later in his career. That he even had a lasting music career was an impressive act of perseverance. The Stanley boys did try other things from time to time, but the music always called them back. In May 1945, just out of high school, Ralph joined the Army and was shipped off to Germany. The fighting was mostly over and there was a lot of cleaning up to do, disarming citizens and the like, but Stanley’s banjo picking caught the attention of his superiors and got him promoted. In the end, though, following orders wasn’t for him.

Back home in rural Virginia, there were more or less two choices: the coal mines or the lumber mills, where Lee Stanley worked. Ralph actually did a short stint in the mills at one point, and hated it. By and large, the brothers promised one another that they would stick together and perform their way out of this brutal employment dead end that stole the youth of so many young men.

None of their half-siblings played music, and Lucy had long ago laid down her clawhammer banjo to raise a family, but Ralph and Carter were determined. Their parents supported their aspirations, too, even though some people in those mountains still frowned upon professional musicians as sinners and ne’er-do-wells—back in the Depression era, even family acts were considered morally suspect. Music was something for church. And indeed, it was at the old Primitive Baptist Church, where Lucy’s brother preached, that the boys got their first taste of the power of gospel music sung a capella. The church didn’t allow musical instruments—only the Lord’s music as lined out by the preacher for his flock to sing.

Those hymns had a profound influence on the boys; besides simply emulating the bands they grew up on—and they did their share of that in the beginning—the Stanleys incorporated the old gospel into their repertoire, sometimes adapting songs they learned in church for the less-pious crowd. Oftentimes preachers they knew would offer them new tunes for consideration. One of my favorites, “The Darkest Hour Is Just Before Dawn,” came to Ralph Stanley in a dream, words and melody, leaving him scrambling for a pen in the wee hours so he could get it down on paper: The darkest hour is just before dawn, the narrow way leads home / lay down your soul at Jesus’ feet / the darkest hour is just before dawn.

More than the words, it’s the Stanley way of singing that can stir the hearts of even nonbelievers. (Ralph recalls a few people finding religion at his shows.) Grief and faith were common themes in Stanley Brothers songs—mothers and daddies dying, lovers betrayed, tormented souls yearning for heaven. Carter played guitar and sang lead baritone while Ralph played banjo and sang high tenor. But banjoists, Ralph now professes, are a dime a dozen. He cared most about the singing; the multipart harmonies—accomplished with help from backing band the Clinch Mountain Boys—gave the Stanleys their distinctive sound.

After the second war, when the brothers were getting their start, bands would work directly out of radio stations, hosting live variety shows. The brothers’ first break was landing a live radio show called Farm and Fun Time; they weren’t paid a dime, but it got their name out so they could start booking paid gigs. Musicianship was key, but you had to be entertainers, too; many a Clinch Mountain Boy doubled as a comedian.

The Stanleys’ often-sorrowful songs were leavened with silliness and spectacle. Over the years, they had one member who played the role of a country simpleton, another did a snazzy bullwhip act, a third was hired for his drop-dead imitations. Yet another—remember the time and place—performed a blackface routine. (Stanley later supported Barack Obama’s bid for president and recorded a radio ad on Obama’s behalf, an endorsement that carried weight among the socially conservative coal-field crowd.)

Ralph Stanley may prefer singing to talking, but Eddie Dean manages to aggravate all kinds of good material out of him. “I wish I could have captured better his sense of humor, so dry it’s parched, and it was damn near impossible to get down on paper,” Dean tells me. Still, you can imagine sitting on the front porch of an old farmhouse, being drawn in by this old man’s endless stories, bringing to life the color and characters of the competitive country music scene from the 1920s on up. Relentless touring, no-good promoters, sketchy record deals, revelry and pranks (Carter would slip laxatives to a rival player). There were drunken brawls and trashed motel rooms and shootings and feuds (a livid Lester Flatt calling Carter out for fisticuffs; Bill Monroe throwing a fit and defecting to Decca after Columbia signed the Stanleys; Ralph fixing to kill the pranking front man of the Seldom Scene). Taken together, Ralph’s musings amount to no less than the oral history of a quintessentially American music scene that was swept from the mainstream by the arrival of rock and roll in the late 1950s. Or, as Stanley puts it in the book: “Elvis just about starved us out.”

Considering that Ralph Stanley has recorded more than 200 LPs and CDs and spent decades touring, you’d think he’d have been living on easy street long ago. And he did do pretty well at various points in his career. But it really wasn’t until the release of the Coen bros’ film O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Stanley’s 2002 Grammy for his gritty a capella version of “O Death” that he finally saw the kind of recognition he deserved.

Released in 2000, the movie was a forgettable Odyssey spoof featuring George Clooney, John Turturro, and Tim Blake Nelson as a trio of musical misfits. But the soundtrack, produced by musician T-Bone Burnett, soared to the top of the country charts. It sold more than 7 million copies and reawakened a national appreciation for a nearly forgotten country sound—a far cry from the Country & Western schmaltz Nashville pumps out. Among the tracks were Ralph Stanley’s “O Death,” the Stanley Brothers’ rendition of “Angel Band,” and two Carter Stanley arrangements of “I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow,” performed by others. Burnett barely scratched the surface, but he mined a vast tradition of old songs about love and love lost, murder, faith, and occasional joy—the story of the Southern mountains, and the Stanley Brothers story, too.

It’s inevitable, when you live to be 82, that you see a lot of friends buried. And Stanley, like his parents, experienced more than his share of sorrow. He’s seen more than one Clinch Mountain Boy pass on. (After one of them was murdered in cold blood by a jealous man, Stanley got the phone call from his bandmate’s 12-year-old son, who’d watched it happen.) There was the fire that burned the old Stanley home to the ground. And perhaps hardest of all, in 1966, Ralph lost his best friend, Carter Stanley, whose weakness for the bottle led to his death of liver disease at age 41. Ralph considered hanging up his banjo, but he didn’t. Rather than fade away into the hills, the quieter Stanley broke out of his wallflower role and took the reins. The rest is music history.

Click here to see more portraits of old-time musicians by photographer Tim Barnwell. You can follow Michael Mechanic on Twitter.