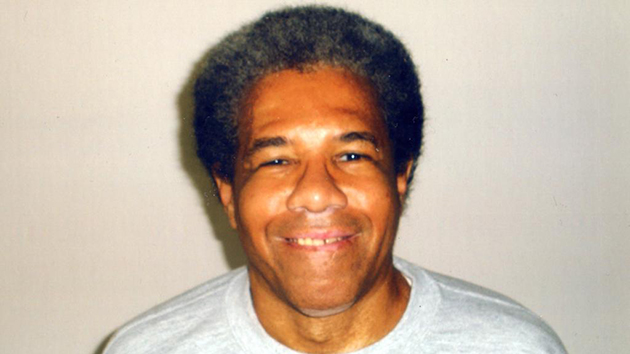

Albert WoodfoxAmnesty International

Imagine spending more than four decades in virtual solitary confinement for a crime you’ve always insisted you didn’t commit—and then, when your freedom is finally at hand, having it snatched away.

That’s the blow the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals dealt on Monday to 68-year-old Albert Woodfox, the last member of the so-called Angola 3 still behind bars. Woodfox, who was twice tried and convicted for his alleged role in the 1972 killing of prison guard Brent Miller, has spent 23 hours a day in a six-by-nine-foot cell at the state penitentiary in Angola, Louisiana, ever since.

The courts eventually overturned both of Woodfox’s convictions based on evidence of racial discrimination and prosecutorial misconduct. In June, after determining that Woodfox couldn’t get a fair trial so long after the fact, a federal judge ordered his immediate release. But the appeals court blocked the move. On Monday, it announced that Louisiana would be free to try Woodfox yet again.

The other Angola 3 members were Herman Wallace—who was released in 2013, but died of cancer three days later—and Robert King, whose conviction was overturned in 2001 after 29 years alone in a tiny cell. (Louisiana’s top prosecutor doesn’t consider this solitary.)

“The men contend that they were targeted by prison authorities and convicted of murder not based on the actual evidence—which was dubious at best—but because they were members of the Black Panther Party’s prison chapter, which was organizing against horrendous conditions at Angola,” wrote James Ridgeway, who covered the Angola 3 for Mother Jones and also profiled the prison’s notorious warden, Burl Cain. “This political affiliation, they say, also accounted for their seemingly permanent stay in solitary.”

Cain confirmed the latter claim during a 2008 deposition, as Ridgeway noted in a story marking the prisoners’ 40th year in solitary. Woodfox’s attorneys addressed the warden: “Let’s just for the sake of argument assume, if you can, that he is not guilty of the murder of Brent Miller.”

Cain responded, “Okay, I would still keep him in CCR [solitary]…I still know that he is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organize the young new inmates. I would have me all kind of problems, more than I could stand, and I would have the blacks chasing after them…He has to stay in a cell while he’s at Angola.”

Amnesty International, which has pursued Woodfox’s release, reacted to the latest court ruling with dismay. Woodfox “remains trapped in a nightmare—both by conditions of solitary confinement and by a deeply flawed legal process that has spanned four decades,” Jasmine Heiss, a senior campaigner for the group, said in a statement.

“Woodfox should have walked free,” she added. “But Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell continues to relentlessly pursue vengeance over justice.”

Indeed, the AG has announced his intention to pursue another trial—even though all of the purported witnesses are dead and the victim’s widow is opposed to it. “In what would surely be one of the most surreal trials of all time,” notes David Cole, who covered the case for The New Yorker, “the state proposes to retry the case by having stand-ins read from the transcripts of these witnesses’ prior testimony.”