On May 23, 2011, the US Supreme Court ruled that conditions in California’s prisons violated the constitutional ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” and affirmed a lower court’s order that the state drastically reduce its inmate population.

Writing on behalf of the court’s five-vote majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy noted that this unprecedented measure had become the only way to remedy the “serious” and “uncorrected” constitutional violations against inmates in the state’s correctional facilities, particularly the sick and mentally ill. “For years the medical and mental health care provided by California’s prisons has fallen short of minimum constitutional requirements and has failed to meet prisoners’ basic health needs. Needless suffering and death have been the well-documented result,” he wrote. “Short term gains in the provision of care have been eroded by the long-term effects of severe and pervasive overcrowding.” His decision included vivid examples of the problem, from open dorms so packed they can’t be effectively monitored, to suicidal inmates “held for prolonged periods in telephone-booth sized cages without toilets.”

More than 162,000 inmates currently reside in California’s prison system. For years, many facilities have held nearly twice the number of prisoners they were built for. As James Sterngold wrote in an article about the overcrowded system for Mother Jones in 2008:

More than 16,000 prisoners sleep on what are known as “ugly beds”—extra bunks stuffed into cells, gyms, day rooms, and hallways. [Governor Arnold] Schwarzenegger has referred to the system as a “powder keg”; in October 2006, he declared a state of emergency, citing the effects of overcrowding—electrical blackouts, sewage spills, dozens of riots, and more than 1,600 attacks on prison guards in the previous year. Last year, a nonpartisan state oversight agency declared the prison system to be “in a tailspin that threatens public safety and raises the risk of fiscal disaster.”

The photographs below provide a glimpse of those extreme conditions: the E-beds (emergency beds) stacked in gyms and dayrooms, the tiny holding cells for mentally ill inmates. All of these photos, some of which were taken by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, were entered as evidence in the California prison case. Three of them (No. 2, No. 3, and the second to last), were appended to the Supreme Court’s majority opinion, suggesting that they had played a role in convincing Kennedy and four other justices to endorse the plan to downsize the state’s prisoner population.

Mule Creek State Prison, July 2006. Mule Creek currently holds more than 3,500 inmates and is 108 percent over capacity. Writing for the majority in Brown v. Plata, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy stated, “The State’s prisons had operated at around 200% of design capacity for at least 11 years. Prisoners are crammed into spaces neither designed nor intended to house inmates. As many as 200 prisoners may live in a gymnasium, monitored by as few as two or three correctional officers…As many as 54 prisoners may share a single toilet.”

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

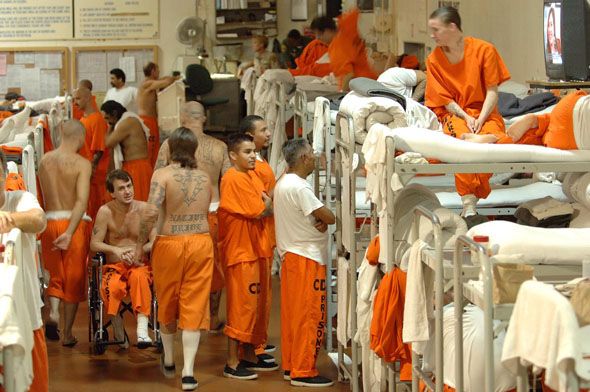

California Institution for Men, August 2006. It currently holds nearly 5,600 inmates and is 97.5 percent over capacity. This photograph was appended to the majority decision in Brown v. Plata.

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Holding cells for prisoners awaiting a “mental-health crisis bed,” Salinas Valley State Prison, July 2008. Writing for the majority in Brown v. Plata, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy stated, “Because of a shortage of treatment beds, suicidal inmates may be held for prolonged periods in telephone-booth sized cages without toilets…A psychiatric expert reported observing an inmate who had been held in such a cage for nearly 24 hours, standing in a pool of his own urine, unresponsive and nearly catatonic. Prison officials explained they had ‘no place to put him.'” This photograph was appended to his decision.

Photo from Brown v. Plata trial evidence

Inmates inside “group cages” in the Administrative Segregation Unit of Mule Creek State Prison, August 2008. In his opinion in Brown v. Plata, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy observed, “Inmates awaiting care may be held for months in administrative segregation, where they endure harsh and isolated conditions and receive only limited mental health services. Wait times for mental health care range as high as 12 months.”

Photo from Brown v. Plata trial evidence

California Institution for Men, August 2006. It currently holds nearly 5,600 inmates and is 97.5 percent over capacity. Writing for the majority in Brown v. Plata, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy observed, “Cramped conditions promote unrest and violence, making it difficult for prison officials to monitor and control the prison population…After one prisoner was assaulted in a crowded gymnasium, prison staff did not even learn of the injury until the prisoner had been dead for several hours.”

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

California Institution for Women, August 2006. It currently holds 3,700 inmates; it is designed to hold 2,004.

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

California State Prison, Los Angeles County, August 2006. It currently holds 4,275 inmates; it is designed to hold 2,300.

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

California State Prison, Los Angeles, in August 2006. It currently holds 4,275 inmates; it is designed to hold 2,300.

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

California State Prison, Los Angeles, in August 2006. It currently holds 4,275 inmates; it is designed to hold 2,300.

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

A concrete cell for an inmate on suicide watch at Wasco State Prison.

Photo from Brown v. Plata trial evidence

Prisoners living in a gym converted into a dorm at Mule Creek State Prison, August 2008. The words on the left wall read, “No Warning Shot Is Required.” This photograph was appended to the majority decision in Brown v. Plata.

Photo from Brown v. Plata trial evidence

California Institution for Men, August 2006. It currently holds nearly 5,600 inmates and is 97.5 percent over capacity. Writing for the majority in Brown v. Plata, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy observed, “Numerous experts testified that crowding is the primary cause of the constitutional violations. The former warden of San Quentin and former acting secretary of the California prisons concluded that crowding ‘makes it “virtually impossible for the organization to develop, much less implement, a plan to provide prisoners with adequate care.”‘”

Photo by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation