In a framed photo of herself taken in 2007, Sharon Galicia stands, fresh-faced and beaming, beside first lady Laura Bush at a Washington, DC, luncheon, thrilled to be honored as an outstanding GOP volunteer. We are in her office in the Aflac insurance company in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and Sharon is heading out to pitch medical and life insurance to workers in a bleak corridor of industrial plants servicing the rigs in the Gulf of Mexico and petrochemical plants that make the plastic feedstock for everything from car seats to bubble gum.

After a 20-minute drive along flat terrain, we pull into a dirt parking lot beside a red truck with a decal of the Statue of Liberty, her raised arm holding an M-16. A man waves from the entrance to an enormous warehouse. Warm, attractive, well-spoken, Sharon has sold a lot of insurance policies around here and made friends along the way.

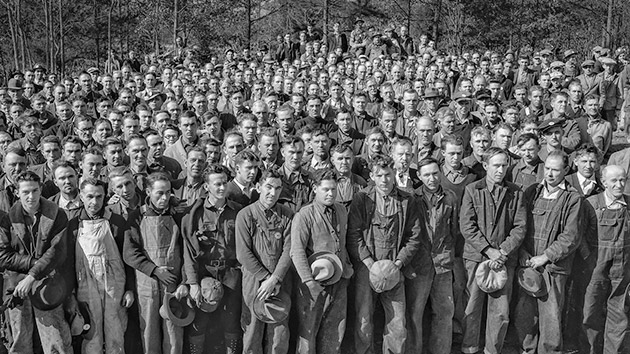

A policy with a weekly premium of $5.52 covers accidents that aren’t covered by a worker’s other insurance—if he has any. “How many of you can go a week without your paycheck?” is part of Sharon’s pitch. “Usually no hands go up,” she tells me. Her clients repair oil platforms, cut sheet metal, fix refrigerators, process chicken, lay asphalt, and dig ditches. She sells to entry-level floor sweepers who make $8 an hour and can’t afford to get sick. She sells to flaggers in highway repair crews who earn $12 an hour, and to welders and operators who, with overtime, make up to $100,000 a year. For most, education stopped after high school. “Pipe fitters. Ditch diggers. Asphalt layers,” Sharon says. “I can’t find one that’s not for Donald Trump.”

I first met Sharon at a gathering of tea party enthusiasts in Lake Charles in 2011. I told them I was a sociologist writing a book about America’s ever-widening political divide. In their 2008 book, The Big Sort, Bill Bishop and Robert Cushing showed that while Americans used to move mainly for individual reasons like higher-paid jobs, nicer weather, and better homes, today they also prioritize living near people who think like they do. Left and Right have become subnations, as George Saunders recently wrote in The New Yorker, living like housemates “no longer on speaking terms” in a house set afire by Trump, gaping at one another “through the smoke.”

I wanted to leave my subnation of Berkeley, California, and enter another as far right as Berkeley is to the left. White Louisiana looked like it. In the 2012 election, 39 percent of white voters nationwide cast a ballot for President Barack Obama. That figure was 28 percent in the South, but about 11 percent in Louisiana.

To try to understand the tea party supporters I came to know—I interviewed 60 people in all—over the next five years I did a lot of “visiting,” as they call it. I asked people to show me where they’d grown up, been baptized, and attended school, and the cemetery where their parents had been buried. I perused high school yearbooks and photograph albums, played cards, and went fishing. I attended meetings of Republican Women of Southwest Louisiana and followed the campaign trails of two right-wing candidates running for Congress.

When I asked people what politics meant to them, they often answered by telling me what they believed (“I believe in freedom”) or who they’d vote for (“I was for Ted Cruz, but now I’m voting Trump”). But running beneath such beliefs like an underwater spring was what I’ve come to think of as a deep story. The deep story was a feels-as-if-it’s-true story, stripped of facts and judgments, that reflected the feelings underpinning opinions and votes. It was a story of unfairness and anxiety, stagnation and slippage—a story in which shame was the companion to need. Except Trump had opened a divide in how tea partiers felt this story should end.

“Hey Miss Sharon, how ya’ doin’?” A fiftysomething man I’ll call Albert led us through the warehouse, where sheet metal had been laid out on large tables. “Want to come over Saturday, help us make sausage?” he called over the eeeeech of an unseen electrical saw. “I’m seasoning it different this year.” The year before, Sharon had taken her 11-year-old daughter along to help stuff the spicy smoked-pork-and-rice sausage, to which Albert added ground deer meat. “I’ll bring Alyson,” Sharon said, referring to her daughter. Some days they’d have 400 pounds of deer meat and offer her some. “They’re really good to me. And I’m there for them too when they need something.”

These men had little shelter from bad news. “If you die, who’s going to bury you?” Sharon would ask on such calls. “Do you have $10,000 sitting around? Will your parents have to borrow money to bury you or your wife or girlfriend? For $1.44 a week, you get $20,000 of life insurance.”

Louisiana is the country’s third-poorest state; 1 in 5 residents live in poverty. It ranks third in the proportion of residents who go hungry each year, and dead last in overall health. A quarter of the state’s students drop out from high school or don’t graduate on time. Partly as a result, Louisiana leads the nation in its proportion of “disconnected youth“—20 percent of 16- to 24-year-olds in 2013 were neither in school nor at work. (Nationally, the figure is 14 percent.) Only 6 percent of Louisiana workers are members of labor unions, about half the rate nationwide.

Louisiana is also home to vast pollution, especially along Cancer Alley, the 85-mile strip along the lower Mississippi between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, with some 150 industrial plants where once there were sugar and cotton plantations. According to the American Cancer Society, Louisiana had the nation’s second-highest incidence of cancer for men and the fifth-highest rate of male deaths from cancer. “When I make a presentation, if I say, ‘How many of you know someone that has had cancer?’ every hand is going to go up. Just the other day I was in Lafayette doing my enrollments for the insurance, and I was talking to this one guy. And he said, ‘My brother-in-law just died. He was 29 or 30.’ He’s the third person working for his company that’s been in their early 30s that’s died of cancer in the last three years. I file tons and tons of cancer claims.”

Sharon also faced economic uncertainty. A divorced mother of two, she supported herself and two children on an ample but erratic income, all from commission on her Aflac sales. “If you’re starting out, you might get 99 ‘noes’ for every one ‘yes.’ After 16 years on the job, I get 50 percent ‘yeses.'” This put her at the top among Aflac salespeople; still, she added, “If it’s a slow month, we eat peanut butter.”

Until a few years ago, Sharon had also collected rent from 80 tenants in a trailer court. Her ex-husband earned $40,000 as a sales manager at Pacific Sunwear, she explained, and helped with child support; altogether it allowed her to pay her children’s tuition at a parochial school and stay current on the mortgage of a tastefully furnished, spacious ranch house in suburban Moss Bluff. She lived in the anxious middle.

And from this vantage point, the lives of renters in her trailer park, called Crestwood Community, had both appalled and unnerved her. Some of her tenants, 80 percent of whom were white, had matter-of-factly admitted to lying to get Medicaid and food stamps. When she’d asked a boy her son’s age about his plans for the future, he answered, “I’m just going to get a [disability] check, like my mama.” Many renters had been, she told me, able-bodied, idle, and on disability. One young man had claimed to have seizures. “If you have seizures, that’s almost a surefire way to get disability without proving an ailment,” she said. A lot of Crestwood Community residents supposedly had seizures, she added. “Seizures? Really?”

As we drove through the vacated lot, we passed abandoned trailers with doors flung open, tall grass pockmarked with holes where mailboxes once stood. Unable to pay an astronomical water bill, Sharon had been forced to close the trailer park, giving residents a month’s notice and provoking their resentment.

In truth, Sharon felt relief. Her renters, she said, had been a hard-living lot. A jealous boyfriend had murdered his girlfriend. Some men drank and beat their wives. One man had married his son’s ex-wife. Beyond that, Sharon had felt unfairly envied by them. “I’ve been called a rich bitch. They think Miss Sharon lives the life of Riley.” And while her home was a 25-minute drive away, the life of her renters had felt entirely too close for comfort. “You couldn’t talk to anyone at Crestwood whose teeth weren’t falling out, gums black, missing teeth,” adding that she gave out toothbrushes and toothpaste one Christmas. “My kids make fun of me because I brush my teeth so much.”

To her, the trailer park both did and did not feel worlds away. For one thing, a person’s standard of living, their worldview and basic identity, seemed already set on a floor of Jell-O. Who could know for sure how you would fare in the era of an expanding bottom, spiking top, and receding middle class?

Sharon’s maternal grandfather had established a successful line of local furniture stores and shown how far up a man with gumption could rise. Sharon herself had graduated magna cum laude from McNeese State University in Lake Charles and been elected president of Republican Women of Southwest Louisiana. But her youngest brother had dropped out of high school and, while very bright and able-bodied, had not found his way. Her father, a plant worker who’d left her mom when Sharon was a teen, had remarried and moved to a trailer in Sulphur with his new wife, a mother of four. Looking around her, Sharon saw family and friends who struggled with bad relationships and joblessness. Some collected food stamps. “I don’t get it,” she said, “and it drives me nuts.”

For Sharon, being on the dole raised basic issues of duty, honor, and shame. It had been hard to collect rent that she knew derived from disability checks, paid, in the end, by hardworking taxpayers like her. “I pay $9,000 in taxes every year and we get nothing for it,” she said. Like others I interviewed, she felt that the federal government—especially under President Obama—was bringing down the hardworking rich and struggling middle while lifting the idle poor. She’d seen it firsthand and it felt unfair.

As we drove from the trailer park to her home, Sharon reflected on human ambition: “You can just see it in some guys’ eyes; they’re aiming higher. They don’t want a handout.” This was the central point of one of Sharon’s favorite books, Barefoot to Billionaire, by oil magnate Jon Huntsman Sr. (whose son ran in the 2012 Republican presidential primary). Ambition was good. Earning money was good. The more money you earned, the more you could give to others. Giving was good. So ambition was the key to goodness, which was the basis for pride.

If you could work, even for pennies, receiving government benefits was a source of shame. It was okay if you were one of the few who really needed it, but not otherwise. Indignation at the overuse of welfare spread, in the minds of tea party supporters I got to know, to the federal government itself, and to state and local agencies. A retired assistant fire chief in Lake Charles told me, “I got told we don’t need an assistant fire chief. A lot of people around here don’t like any public employees, apart from the police.” His wife said, “We were making such low pay that we could have been on food stamps every month and other welfare stuff. And [an official] told our departments that if we went and got food stamps or welfare it would look bad for Lake Charles so that he would fire us.” A public school teacher complained, “I’ve had people tell me, ‘It’s the teachers who need to pass the kids’ tests.’ They have no idea what I know.” A social worker who worked with drug addicts said, “I’ve been told the church should take care of addicts, not the government.” Both receivers and givers of public services were tainted—in the eyes of nearly all I came to know—by the very touch of government.

Sharon especially admired Albert, a middle-aged sheet metal worker who could have used help but was too proud to ask for it. “He’s had open-heart surgery. He’s had stomach surgery. He’s had like eight surgeries. He’s still working, though. He wants to work. He’s got a daughter in jail—her third DUI, so he’s raising her son—and this and that. But he doesn’t want anything from the government. He’s such a neat guy.” There was no mention of the need for a good alcoholism rehab program for his daughter or after-school programs for his grandson. Until a few days before his death Albert continued working, head high, shame-free.

Sharon’s politics were partly rooted, it seemed, in the class slippage of her childhood. As the oldest of three, the “little mama” to two younger brothers, she said, “I got them up in the morning, made their beds for them, so my mama wouldn’t come down hard on them.” Sharon’s mother, the daughter of that prosperous furniture store owner, had grown up with a black maid who’d made her bed for her. She’d married a highly intelligent but high-school-educated plant worker, a Vietnam vet who never spoke of the war and seemed in search of peace and quiet. Privileges came and went in deeply unsettling ways and made a person want to hold on to a reassuring past. “One time when I had to travel to Florida on work, I left the kids with my mom, and Bailey called me for help: ‘Grandma’s forcing me to make her bed!'” Sharon answered, “I’m really sorry, Bailey; make her bed.”

With the proud memory of an affluent Southern white girlhood, her mother took a dim view of the federal government. She’d trained as a social worker, volunteered in a women’s prison, and remembered its inmates in her daily prayer. A devoted Christian, Sharon’s mother believed in a generous church. But government benefits were a very different story. Taking them meant you’d fallen and weren’t proudly trying to rise back up.

As we pulled up to her home, Sharon reflected on various theories her mother had. “Have you heard of the Illuminati? The New World Order?” Sharon asked so as to prepare me. “I’m tea party,” Sharon said, “but I don’t go along with a lot that my mom does.” Whether they clung to such dark notions or laughed them off, tea party enthusiasts lived in a roaring rumor-sphere that offered answers to deep, abiding anxieties. Why did President Obama take off his wristwatch during Ramadan? Why did Walmart run out of ammunition on the third Tuesday in March? Did you know drones can detect how much money you have? Many described these as suspicions other people held. Many seemed to float in a zone of half-belief.

The most widespread of these suspicions, of course—shared by 66 percent of Trump supporters—is that Obama is Muslim.

What the people I interviewed were drawn to was not necessarily the particulars of these theories. It was the deep story underlying them—an account of life as it feels to them. Some such account underlies all beliefs, right or left, I think. The deep story of the right goes like this:

You are patiently standing in the middle of a long line stretching toward the horizon, where the American Dream awaits. But as you wait, you see people cutting in line ahead of you. Many of these line-cutters are black—beneficiaries of affirmative action or welfare. Some are career-driven women pushing into jobs they never had before. Then you see immigrants, Mexicans, Somalis, the Syrian refugees yet to come. As you wait in this unmoving line, you’re being asked to feel sorry for them all. You have a good heart. But who is deciding who you should feel compassion for? Then you see President Barack Hussein Obama waving the line-cutters forward. He’s on their side. In fact, isn’t he a line-cutter too? How did this fatherless black guy pay for Harvard? As you wait your turn, Obama is using the money in your pocket to help the line-cutters. He and his liberal backers have removed the shame from taking. The government has become an instrument for redistributing your money to the undeserving. It’s not your government anymore; it’s theirs.

I checked this distillation with those I interviewed to see if this version of the deep story rang true. Some altered it a bit (“the line-waiters form a new line”) or emphasized a particular point (those in back are paying for the line-cutters). But all of them agreed it was their story. One man said, “I live your analogy.” Another said, “You read my mind.”

The deep story reflects pain; you’ve done everything right and you’re still slipping back. It focuses blame on an ill-intentioned government. And it points to rescue: The tea party for some, and Donald Trump for others. But what had happened to make this deep story ring true?

Most of the people I interviewed were middle class—and nationally more than half of all tea party supporters earn at least $50,000, while almost a third earn more than $75,000 a year. Many, however, had been poor as children and felt their rise to have been an uncertain one. As one wife of a well-to-do contractor told me, gesturing around the buck heads hanging above the large stone fireplace in the spacious living room of her Lake Charles home, “We have our American Dream, but we could lose it all tomorrow.”

Being middle class didn’t mean you felt secure, because that class was thinning out as a tiny elite shot up to great wealth and more people fell into a life of broken teeth, unpaid rent, and shame.

Growing up, Sharon had felt the struggle it took for her family to “stand in line” in a tumultuous world. Three years after her father wordlessly left home when she was 17, Sharon married, soon embracing a covenant marriage—one that requires premarital counseling and sets stricter grounds for divorce. But then they did divorce, and Sharon, once the little mother to her own siblings, now found herself a single mother of two—a mom and dad both. She was doing her level best but wondered why the travails of others so often took precedence over families such as her own. Affirmative-Action blacks, immigrants, refugees seemed to so routinely receive sympathy and government help. She, too, had sympathy for many, but, as she saw it, a liberal sympathy machine had been set on automatic, disregarding the giving capacity of families like hers.

Or as one tea partier wrote to me: “We’re so broke. Where does this food & welfare money come from? How can free stuff (including college, which my 4.2 student needs) even be on the table when the US owes $19,343,541,768,824.00 as of July 1? Is it just me or does it seem like the only thing ANYONE cares about is themselves and their immediate circumstances?”

Pervasive among the people I talked to was a sense of detachment from a distant elite with whom they had ever less contact and less in common. And, as older white Christians, they were acutely aware of their demographic decline. “You can’t say ‘merry Christmas,’ you have to say ‘happy holidays,'” one person said. “People aren’t clean living anymore. You’re considered ignorant if you’re for that.” An accountant told me, “Other people say, ‘You’re too hard-nosed about [morals].’ Better to be hard-nosed than to be like it is now, so permissive about everything.” They also felt disrespected for holding their values: “You’re a weak woman if you don’t believe that women should, you know, just elbow your way through society. You’re not in the ‘in’ crowd if you’re not a liberal. You’re an old-fashioned old fogey, small thinking, small town, gun loving, religious,” said a minister’s wife. “The media tries to make the tea party look like bigots, homophobic; it’s not.” They resented all labels “the liberals” had for them, especially “backward” or “ignorant Southerners” or, worse, “rednecks.”

Liberal television pundits and bloggers took easy potshots at them, they felt, which hardened their defenses. Their Facebook pages then filled with news coverage of liberals beating up fans at Trump rallies and Fox News coverage of white policemen shot by black men.

For some, age had also become a source of humiliation. One white evangelical tea party supporter in his early 60s had lost a good job as a sales manager with a telecommunications company when it merged with another. He took the shock bravely. But when he tried to get rehired, it was terrible. “I called, emailed, called, emailed. I didn’t hear a thing. That was totally an age discrimination thing.” At last he found a job at $10 an hour, the same wage he had earned at a summer factory union job as a college student 40 years ago. Age brought no dignity. Nor had the privilege linked to being white and male trickled down to him. Like Sharon’s clients in the petrochemical plants, he felt like a stranger in his own land.

But among those walking in this wilderness, Trump had opened up a divide. Those more in the middle class, such as Sharon, wanted to halt the “line-cutters” by slashing government giveaways. Those in the working class, such as her Aflac clients, were drawn to the idea of hanging on to government services but limiting access to them.

Sharon was a giving person, but she wanted to roll back government help. It was hard supporting her kids and being a good mom too. Managing the trailer park had called on her grit, determination, even hardness—which she regretted. She mused, “Having to cope, run the trailer court, even threaten to shoot a dog”—her tenant’s pet had endangered children—”it’s hardened me, made me act like a man. I hate that. It’s not really me.” There was a price for doing the right and necessary thing, invisible, she felt, to many liberals.

And with all the changes, the one thing America needed, she felt, was a steady set of values that rewarded the good and punished the bad. Sharon honored the act of giving when it came from the private sector. “A businessperson gives other people jobs,” she explained. She was proud to have employed two people at the trailer park, and sad she’d had to let them go. “I promised, ‘The whole month of October you’re going to get paid because you’re out looking for another job.’ That’s a whole month. I feel an obligation.” If you rose up in business, you took others with you, and this would be a point of pride. There was nothing wrong with having; if you had, you gave. But if you took—if you took from the government—you should be ashamed.

It was the same principle evident across the conservative movement, the one Mitt Romney had hewed to when he disparaged 47 percent of Americans as people who “pay no income tax” and “believe that they are victims,” or when Romney’s running mate, Paul Ryan, spoke of “makers and takers.” The rich deserve honor as makers and givers and should be rewarded with the proud fruits of their earnings, on which taxes should be drastically cut. Such cuts would require an end to many government benefits that were supporting the likes of Sharon’s trailer park renters. For her, the deep story ended there, with welfare cuts.

But for the blue-collar workers in the plants she visited, the guys who loved Donald Trump, it did not. When Sharon and I last had dinner in March, shortly after Trump’s 757 jet swooped into New Orleans for his boisterous rally ahead of his big win in the Louisiana primary, Sharon told me about conversations with her Aflac clients that had shocked her. “They were talking about getting benefits from the government as if it were a good thing—even the white guys.”

Sharon was leery of Trump and tried to puzzle out his appeal for them. “For the first few weeks I was very intrigued. I was like, ‘What is this guy talking about? He’s a jerk, but I like some of what he says.’ But when you really start listening, no!” What troubled her most was that Trump was not a real conservative, that he was for big government. “Is he going to be a dictator? My gut tells me yes, he’s an egomaniac. I don’t care if you’re Ronald Reagan, I don’t want a dictator. That’s not America.” So, I asked, what did her clients see in Trump? “They see him as very strong. A blue-collar billionaire. Honest and refreshing, not having to be politically correct. They want someone that’s macho, that can chew tobacco and shoot the guns—that type of manly man.”

But something else seemed at play. Many blue-collar white men now face the same grim economic fate long endured by blacks. With jobs lost to automation or offshored to China, they have less security, lower wages, reduced benefits, more erratic work, and fewer jobs with full-time hours than before. Having been recruited to cheer on the contraction of government benefits and services—a trend that is particularly pronounced in Louisiana—many are unable to make ends meet without them. In Coming Apart: The State of White America, conservative political scientist Charles Murray traces the fate of working-age whites between 1960 and 2010. He compares the top 20 percent of them—those who have at least a bachelor’s degree and are employed as managers or professionals—with the bottom 30 percent, those who never graduated from college and are employed in blue-collar or low-level white-collar jobs. In 1960, the personal lives of the two groups were quite similar. Most were married and stayed married, went to church, worked full time (if they were men), joined community groups, and lived with their children.

A half-century later, the 2010 top looked much like their counterparts in 1960. But for the bottom 30 percent, family life had drastically changed. While more than 90 percent of children of blue-collar families lived with both parents in 1960, by 2010, 22 percent did not. Lower-class whites were also less likely to attend church, trust their neighbors, or say they were happy. White men worked shorter hours, and those who were unemployed tended to pass up the low-wage jobs available to them. Another study found that in 2005, men with low levels of education did two things substantially more than both their counterparts in 1985 and their better-educated contemporaries: They slept longer and watched more television.

How can we understand this growing gap between male lives at the top and bottom? For Murray, the answer is a loss of moral values. But is sleeping longer and watching television a loss of morals, or a loss of morale? A recent study shows a steep rise in deaths of middle-aged working-class whites—much of it due to drug and alcohol abuse and suicide. These are not signs of abandoned values, but of lost hope. Many are in mourning and see rescue in the phrase “Great Again.”

Trump’s pronouncements have been vague and shifting, but it is striking that he has not called for cuts to Medicaid, or food stamps, or school lunch programs, and that his daughter Ivanka nods to the plight of working moms. He plans to replace Obamacare, he says, with a hazy new program that will be “terrific” and that some pundits playfully dub “Trumpcare.” For the blue-collar white male Republicans Sharon spoke to, and some whom I met, this change was welcome.

Still, it was a difficult thing to reconcile. How wary should a little-bit-higher-up-the-ladder white person now feel about applying for the same benefits that the little-bit-lower-down-the-ladder people had? Shaming the “takers” below had been a precious mark of higher status. What if, as a vulnerable blue-collar white worker, one were now to become a “taker” oneself?

Trump, the King of Shame, has covertly come to the rescue. He has shamed virtually every line-cutting group in the Deep Story—women, people of color, the disabled, immigrants, refugees. But he’s hardly uttered a single bad word about unemployment insurance, food stamps, or Medicaid, or what the tea party calls “big government handouts,” for anyone—including blue-collar white men.

In this feint, Trump solves a white male problem of pride. Benefits? If you need them, okay. He masculinizes it. You can be “high energy” macho—and yet may need to apply for a government benefit. As one auto mechanic told me, “Why not? Trump’s for that. If you use food stamps because you’re working a low-wage job, you don’t want someone looking down their nose at you.” A lady at an after-church lunch said, “If you have a young dad who’s working full time but can’t make it, if you’re an American-born worker, can’t make it, and not having a slew of kids, okay. For any conservative, that is fine.”

But in another stroke, Trump adds a key proviso: restrict government help to real Americans. White men are counted in, but undocumented Mexicans and Muslims and Syrian refugees are out. Thus, Trump offers the blue-collar white men relief from a taker’s shame: If you make America great again, how can you not be proud? Trump has put on his blue-collar cap, pumped his fist in the air, and left mainstream Republicans helpless. Not only does he speak to the white working class’ grievances; as they see it, he has finally stopped their story from being politically suppressed. We may never know if Trump has done this intentionally or instinctively, but in any case he’s created a movement much like the anti-immigrant but pro-welfare-state right-wing populism on the rise in Europe. For these are all based on variations of the same Deep Story of personal protectionism.

During my last dinner with Sharon, over gumbo at the Pujo Street Café in Lake Charles, our talk turned to motherhood. Sharon wanted to give Bailey and Alyson the childhood she never had. She wanted to expose them to the wider world, and to other ways of thinking. “When I was a kid, the only place I’d ever been, outside of Louisiana, was Dallas,” she mused. “I want my kids to see the whole world.” She’d taken them on an American-history tour through Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Washington, DC, where nine years ago she’d lunched with Laura Bush. She’d taken them to Iceland, which “they loved,” and she’d just scored three round-trip tickets for a surprise tour of Finland, Sweden, and Russia.

But Sharon’s gift to her children of a wider world carried risks. Her thoughtful 17-year-old, Bailey, had been watching Bernie Sanders decry the growing gap between rich and poor, push for responsive government, and propose free college tuition for all. “Bailey likes Sanders!” Sharon whispered across the table, eyebrows raised. Sanders had different ideas about good government and about shame, pride, and goodness. Bailey was rethinking these values himself. “He can’t stand Trump,” Sharon mused, “but we’ve found common ground. We both agree we should stop criminalizing marijuana and stop being the world’s policeman, though we completely disagree on men using women’s bathrooms.” The great political divide in America had come to Sharon’s kitchen table. She and Bailey were earnestly, bravely, searchingly hashing it out, with young Alyson eagerly listening in. Meanwhile, this tea party mom of a Sanders-loving son was reluctantly gearing up to vote for Donald Trump.