Attorneys at a makeshift office for volunteer attorneys at Chicago's O'Hare International AirportErin Hooley/TNS via ZUMA Wire

On a gloomy afternoon at San Francisco International Airport, a dozen or so men and women assembled by the terminal’s Starbucks, waiting for their assignments. Behind them, two people huddled over laptops, flanked by a printer, a whiteboard, and stacks of paperwork. A small cardboard sign, cut from a FedEx box, said “Lawyer” in English, Arabic, and Farsi. For weeks, this desk was the headquarters for a temporary legal office that helped travelers affected by President Donald Trump’s sweeping executive orders on immigration.

Legal clinics like the one at SFO sprang up in major airports across the country, including in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York. Staffed entirely by volunteers, they were an early sign of the rapid grassroots organizing taking place among lawyers, civil rights activists, and everyday people in response to the executive orders.

Federal courts have suspended the orders, which banned immigrants from seven predominantly Muslim countries as well as all refugees from entering the United States. Volunteer lawyers are no longer physically stationed at airports—they are on call to assist passengers who need help. But as the Trump administration continues to expand the scope of immigration enforcement, the clinics offer an intriguing snapshot of what future rapid-response aid may look like as groups move quickly to help people who may be affected.

Boots on the ground

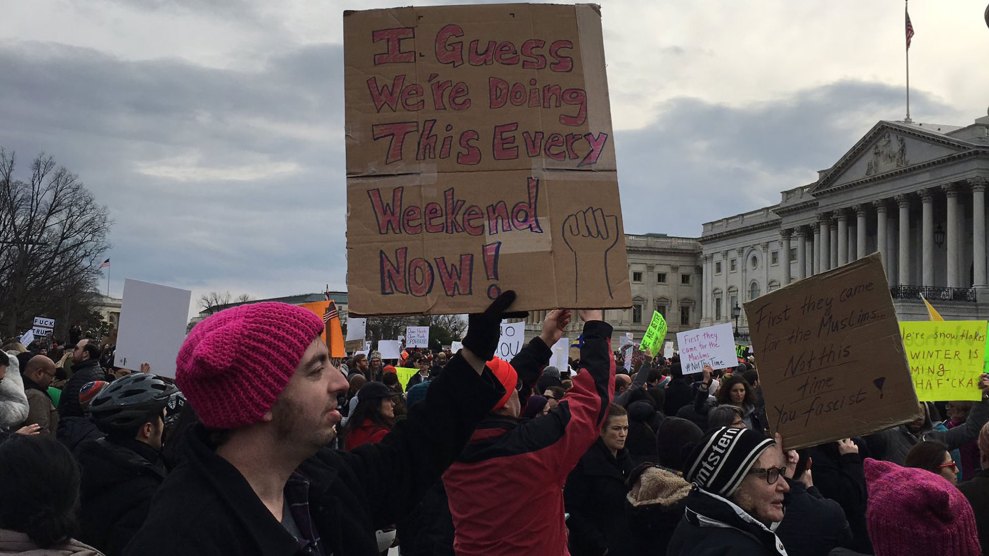

The airport legal clinics formed hours after Trump signed his January 27 executive order. The order’s hasty implementation led to chaos, as Customs and Border Protection officers began detaining travelers who came from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen the first weekend the immigration ban was enforced. It drew harsh criticism from civil rights groups, and thousands of protesters clogged airports.

While state attorneys general and national groups such as the Council on American-Islamic Relations and the American Civil Liberties Union mounted legal challenges against Trump’s executive order in federal courts, the volunteer attorneys in airports focused on providing support to individual travelers. During the first days of the travel ban, large organizations such as the International Refugee Assistance Project and the ACLU organized attorneys at airports. Later, this shifted to local groups.

“They’re the command centers, while we’re the boots on the ground,” said Julia Wilson, the chief executive officer of OneJustice, one of several nonprofits that coordinated volunteers for the clinics in the Bay Area.

In Los Angeles, clinic volunteers have assisted more than 300 passengers, while volunteers at SFO have conducted nearly 100 intake interviews since the executive order was signed, said Wilson. The San Francisco airport numbers are an undercount, she said, since the airport was flooded with protesters during the first days the immigration ban was in place, and volunteers could not track exact numbers.

At SFO’s international terminal, Renée Schomp, a petite woman with wavy brown hair, stepped forward and began handing out assignments. Arabic and Farsi speakers would serve as interpreters, standing near the arrival gates with signs offering free legal advice. Two volunteers would track important flights. Attorneys would handle intake forms.

It was 4 p.m. and only a handful of people were in the terminal. Schomp pointed to the gate at her left.

“It might seem like you’re wasting your time, or you might wonder why you decided to come here,” Schomp said. But as soon as flights landed, passengers would soon be streaming out the gates—and the volunteers must be ready.

Think of yourselves as firefighters, she said. “Firefighters aren’t fighting fires all the time. Sometimes they’re just sitting around playing cards,” she said. “But they’re ready to jump up and take action when the fire actually comes.”

The volunteers’ main goal was to gather and disseminate information, especially about how Customs and Border Protection officers were complying with court orders.

“We would ask folks, ‘Were you asked any religious questions? Were you asked about any political practices’?” says Junaid Sulahry, one of the volunteer lawyers. “We were trying to gain a sense of whether people were being pulled into secondary screening based off how they look, or if [CBP officers] were engaging in inappropriate questioning.”

Sulahry says he spoke to one Iranian national who had been placed in secondary screening for four hours. “We hesitated to approach her because she was in tears,” he says.

Attorneys aimed to monitor CBP officers’ actions and document anything unusual that happened to passengers. They interviewed passengers who wanted to share their own experience going through customs, as well as passengers who may have witnessed something and wanted to report it. Depending on the case, they provided legal advice or made referrals to civil rights organizations or congressional officials if an incident was particularly severe.

In the first few days of the ban, civil rights groups struggled to get information from CBP officers about who may or may not have been detained or deported.

“We had no access to our clients,” says Nicholas Espíritu, a staff attorney with the National Immigration Law Center. “It was like a black box.”

The Department of Homeland Security and the White House have been criticized for the chaotic rollout of the executive order, as well as a lack of transparency surrounding the number of people affected. (White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer, as well as Trump, initially said only 109 people were affected by the ban. CBP now says on its website that more than 1,000 people were recommended denial of boarding.)

On February 1, the DHS inspector general announced it would conduct a review of the department’s implementation of the executive order “in response to congressional request and whistleblower and hotline complaints.” The watchdog office would also review whether DHS officials complied with court orders and allegations of misconduct.

“I was so angry”

Local community groups such as the Asian Law Caucus say monitoring also helps provide resources for family members who may be targeted by the ban.

“There’s a lot of confusion, anxiety, and fear about what is happening and what will happen to family members abroad,” says Elica Vafaie, a staff attorney with the Asian Law Caucus. Without lawyers or other volunteers present, families would have little access to information or resources in case something does happen.

Many of the volunteers I met at the clinic had attended protests of the executive order at the airport or had heard of the clinic online and signed up. Negeen Etemad who is from San Diego and was volunteering as a Farsi interpreter, found out about the clinic through Facebook. For her, the work felt personal: Her uncle, a green card holder from Iran, had been detained for 13 hours after the executive order took effect.

“My family was frantic,” says Etemad, 26. “I was physically sick because I was so angry.”

Cori Van Allen, an accountant based in the Bay Area, told me she heard of the clinic through work and wanted to help in any way she could. “I’m concerned over how this ban was rolled out—it feels unconstitutional, like we’re singling out people in a way that just feeds into ISIS propaganda,” said Van Allen, 47. “I don’t feel like it makes me any safer.”

As I watched the volunteers work, I could see how organized the clinic was. Volunteers worked in four-hour shifts, staffing the airport from 8 a.m. until 11 p.m. At least one attorney would remain on call overnight. Name tags were color-coded—orange meant you were an immigration attorney; green was for coordinators. A stack of clear plastic boxes tucked underneath the chairs were crammed with supplies: Post-it notes, Sharpies, Kashi bars, and intake forms. Pizza arrived around mid-afternoon, carried in by a volunteer with a white name tag.

The airport followed a rhythm: quiet at one moment, then bustling with people the next. Toward evening, a woman and her daughter came by to ask for advice. The woman’s mother was an Iranian green card holder, and though the White House eventually said it would allow green card holders to enter the country, she wanted to talk to the lawyers just in case.

Another man sitting near the clinic leaned over and told the lawyers he was grateful for their work. He said he was expecting a relative to arrive and it had been an hour since the flight landed at 4:30 p.m. Should he be worried?

After 15 minutes, the Iranian woman happily returned with her mother and filled out a quick intake form. The man’s relative also emerged from the gate. They loaded up a luggage cart, waving as they passed by. The evening volunteers’ shifts had begun. One man knelt on the ground to draw a larger “lawyer” sign on a white poster, slowly tracing the letters in black ink.

For organizers and civil rights groups, the airport legal clinics have helped lay the groundwork for future rapid-response legal efforts, showing how quickly volunteers can show up and the willingness among groups to share information and resources. Now organizers are likely to shift toward helping undocumented immigrants by providing free legal services and setting up know-your-rights trainings that can be deployed quickly.

“The legal profession as a whole is standing up,” said Wilson.