Ta-Nehisi Coates speaks on a panel at Howard University in February 2016.Cheriss May/NurPhoto/ZUMA

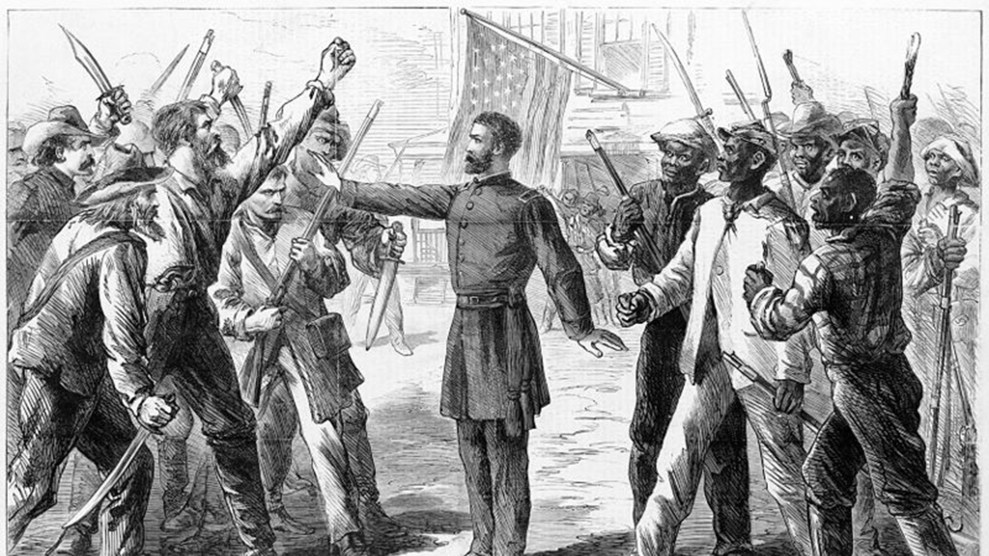

We Were Eight Years In Power, the new book by Atlantic magazine writer and MacArthur “Genius Grant” winner Ta-Nehisi Coates, makes a masterful new work out of old ideas. Coates’ latest draws its name from an 1895 quote by former black South Carolina congressman Thomas Miller, mourning the end of Reconstruction. It consists of eight essays Coates published in The Atlantic during each of former President Barack Obama’s eight years in office.

Punctuating the essays—which include widely read pieces such as Coates’ 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations” and 2016’s “My President Was Black”—are notes Coates composed for the book reflecting on where he was at in life at that time, why he was writing, and the turning points in his growth as a public thinker. Reading through the notes—and Coates’ evolving analyses of race in America—there emerges a picture of his own intellectual path, and how he came to the harsh realization that white supremacy remains a governing force in America society.

The book concludes with an epilogue—his latest essay, “Donald Trump Is the First White President”—that tries to make sense of the present by examining the role of white supremacy in Trump’s rise to power.

Mother Jones: Let’s talk about your decision to expound on “Good Negro Government”—that is, black respectability politics.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: The basic underlying theory of everything is that if we conduct ourselves appropriately, we’ll be rewarded. But for black people the question becomes, “What’s the relationship between that and political reform? Is representing well a kind of political advocacy?” Maybe it is. Maybe it means something when you wear a suit to a rally. But it’s often used as a way of getting around very hard realities and limitations. What is the mass behavioral change that you’ll make in the lives of 40 million [black] people that will change a 1-to-20 wealth gap? For every nickel a black family has, a white family has a dollar. What’s going to bring down the incarceration rate? That ethic [of Good Negro Government] is insufficient. So why do we keep returning to it? That’s what I was thinking about.

MJ: Some of your most astute observations are found in your notes rather than the essays themselves. Why did you decide to include those notes?

TC: As I looked back over the essays and some of the blogging I did around them, it became clear to me that there was something else there. I thought there was a story to tell. People see you and assume you were always that way. So I wanted to talk to young writers about what the road is that they should expect to face so they can be clear about the business they’re getting into.

MJ: What did it mean for you to see Barack Obama run for president on a platform of hope and change, only to then watch Donald Trump run a campaign based on fear and regression?

TC: There was no other way you were going to get a black president. But I didn’t think a black president would happen in my lifetime. To bear witness to it, to see him open himself up in a way that allowed him to talk to all kinds of folks, and to see some of those folks open themselves up and actually listen in a way that I didn’t expect them to was a huge surprise. But Trump proved that [white] folks don’t necessarily need any of that—or intelligence or prudence—to be elected. People resorted to tribalism, and it’s really sad. There’s great damage being done right now. The biggest thing is the destruction of norms, the idea that you don’t brag about sexual assault and then become president. That’s gone now.

MJ: Now that we’ve had a black president, how does that change things for the next black politician who throws his hat in the ring?

TC: They’re not a stranger anymore. These things build on each other. When Jesse Jackson ran in 1988, one of the big changes he made was proportional delegation, so states would not be winner-take-all. In 2008, Obama was able to use proportional delegation to win. So in states where he lost, he could still keep it close and win some delegates, and then blow folks out in other states during the primaries. So Jackson helped, in a literal sense, make Obama possible. In that same way, Obama revealed a coalition that folks can activate and take advantage of. That’s true of the next Hispanic presidential candidate as well.

MJ: In your essay “Fear of a Black President,” you write that Obama had to shy away from talking about race in order to win white voters in 2008. Does Trump make it easier or harder for a black presidential candidate to talk about race now?

TC: It’s never easy. I don’t think he makes it any easier. Does he make it harder? That might depend on the candidate and their political agility.

MJ: What do you mean by that?

TC: How they speak. Obama was agile. He could talk to five different constituencies at the same time. To not make one group feel as though they’re being forgotten even as you address another group is hard to do.

MJ: When do you think we will see another black president?

TC: It could be next cycle, because of the differences in demographics in the two parties. In the Democratic Party, in a state like South Carolina, you have to get 50 or 60 percent of black primary voters, so [a black candidate] actually has an advantage. What that means at the national level, I don’t know. But the possibility is definitely there.

MJ: Do you think we’re ready to elect a black woman as president?

TC: I do. I don’t think it’s a question of being ready. I think it’s the way the demographics are set up within the primary system. It’s easy for me to see somebody getting that nomination. Once they get that nomination all bets are off. It doesn’t mean that the path is not hard, but I certainly think it’s possible. It wouldn’t surprise me if Kamala Harris is the Democratic nominee [in 2020].

MJ: A decade ago you thought a black president was impossible. Now you see the second one as a given—and so soon.

TC: I might be wrong about that, but it’s what I think.

MJ: What’s the most lasting consequence of Obama’s presidency for black people—discounting the election of Donald Trump?

TC: Health care. And, depending on what happens in this next [2018] election, probably federal police reform. But I think really it’s the symbolism.

MJ: How does the symbolism help black people?

TC: You always need stories and inspiration. What policy did Fredrick Douglass actually pass? He was a forceful advocate for emancipation, but it’s clear to me that the historical force that did it was the Civil War. But when I read Douglass’ story—how he learned to read, how he rose from nothing—I take great inspiration from that. It makes me walk through the world differently.

MJ: You get that from Obama, too?

TC: I do. No matter what happens, what his election signaled to people was a moment of possibility and acceptance. I have picked that apart in all sorts of ways, and there are qualifiers on it. But what I’m talking about is not the logic of it, it’s the feeling that inspires people.

MJ: You’ve sometimes been critiqued as a writer who deals in racial theory while remaining apolitical and not offering actual answers for how to grapple with the realities of racism. What do you make of that analysis?

TC: That’s fucking ridiculous! That’s what “The Case for Reparations” is! There are facts and numbers all through that piece. But people don’t like the answer I give. I don’t know when reparations became apolitical or just a symbolic fight. I don’t know when decarceration became an apolitical stance. I think what they want is a kind of how-to to activism. But that’s what activists do! That’s not what journalists do. We have plenty of people doing that work, so I don’t know why people are looking to me for that.

MJ: It seems like you’ve become a favorite of liberal white people who are looking to prove that they “get it” when it comes to racism. Do you agree with that?

TC: People say that, but when I wrote “Donald Trump Is the First White President,” I was catching it from all corners. I had white liberals write into The Atlantic to critique the piece. The same with “The Case for Reparations.” I found myself in arguments. If George Packer isn’t a white liberal, I don’t know who is. If Johnathan Chait isn’t a white liberal, I don’t know who is. So when people say that, I think, “Who are you talking about?”

MJ: What kinds of critiques have you gotten for “The First White President?”

TC: The basic idea is that I was underplaying class. And that’s the argument that I make in the piece—that there’s a thread that you can string through neoliberals to mainline liberals to leftists. From Hillary Clinton all the way to Bernie Sanders—and Obama, too. And that is that you can deal with the problems of racism by addressing them through class. I obviously have my problems with that.

MJ: Who’s your target audience?

TC: I imagine being at Howard University 20 years ago and reading something like “The Bell Curve” in the New Republic. I remember how that made me feel—and that when I read magazines like The Atlantic, like The New Yorker, there wasn’t anybody writing from the place that I came from. There was nobody analyzing politics from the perspective of someone who had come up in West Baltimore during the crack era, these cities where black people grew up. I want young kids who came up like me to read my work and feel like they’re being seen and heard. There’s so much analysis out there, including on the sympathetic left, that tries to forget black folks because we’re so inconvenient for this [America] project. So I write for that young person who feels like they want to read intelligent things, but want people to acknowledge their life, and their history, and their culture, and the importance of it.

MJ: The black kid in Baltimore.

TC: That’s it!

MJ: How did you feel when Toni Morrison compared you to James Baldwin?

TC: I didn’t take it as an award, I took it as a charge. By which I mean, I had to write with a certain force and uphold the legacy. Ancestry is important to me. I understand what Baldwin did for me. So in my mind I have to pay that back, and I have a responsibility to other folks. When somebody like Toni Morrison, a Howard University graduate who walked the same campus that I walked and took classes from Elaine Locke—literally a link directly back to the Harlem Renaissance—tells you, “You got the spirit,” I take that seriously. I think about it when I’m writing, and when I’m bullshitting and should be writing.

MJ: How has reporting on race changed since the election, and how should it change?

TC: People who doubted the impact of race can see it a lot more now. For reporters, there’s a lot more clarity about the impact that race actually has. Donald Trump makes denial a little harder. I pick up the New York Times and the Washington Post and The New Yorker and see great reporting. I can’t tell you what Fox News or CNN is doing. But the places I go for news, I feel like they’re doing a pretty good job. I think reporters can always be more historical. But I think we’re getting better at that.

MJ: How do you see as your role as a writer in the Trump era?

TC: The same thing I was trying to do before, and that is pursue a line of questioning that is deeply central to American identity: the force and the weight of the legacy and the present practices of white supremacy in this country. My job is to be as aggressive as I possibly can about that line of questioning.