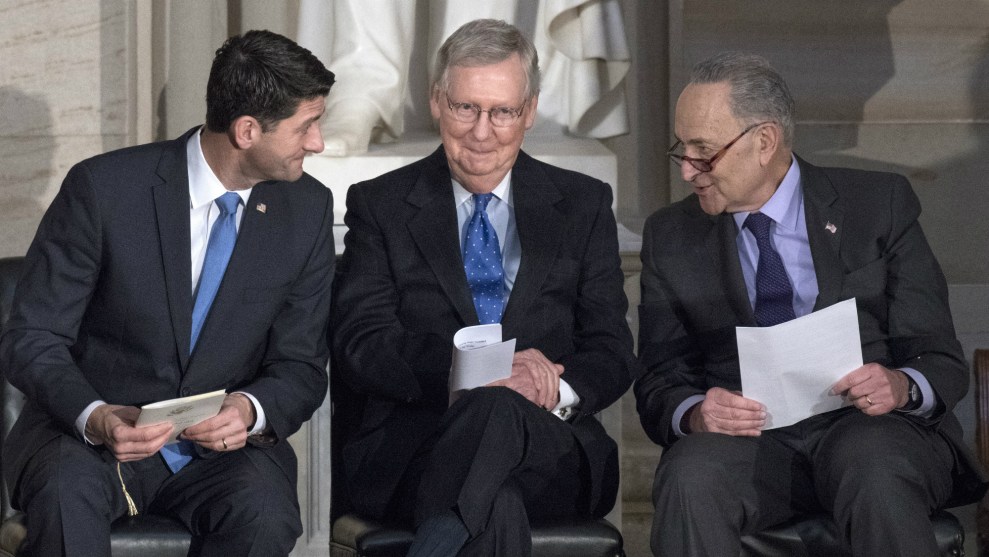

Ron Sachs/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

Once again, the hours are counting down to a government shutdown.

For close to a decade, the federal government has functioned more or less continuously under such a threat. In 2011, a far-right contingent of Republicans in Congress, swept into office by the tea party wave, first started wielding the possibility of a shutdown to advance its agenda of slashing federal spending and shrinking the size of the government. Today, both parties use the threat of a shutdown as leverage to enact their preferred policies.

The possibility of a shutdown looms because our divided Congress can’t pass an annual budget on time or even at all. Instead, it funds the federal government in short, incremental bursts, passing what are known as continuing resolutions to keep the government operating for weeks or months at a time. In recent years, as the latest continuing resolution neared its expiration date, another round of brinksmanship began, with the clock ticking until funding ran out.

Congressional Republicans last followed through on such a threat in October 2013, forcing a partial shutdown that lasted 16 days. Some 800,000 federal employees were furloughed. A million more employees suffered delays in receiving their paychecks. Credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s said the shutdown sucked $24 billion out of the economy.

That’s the situation right now: Democrats and Republicans are locked in negotiations over funding for President Donald Trump’s border wall and securing a deal on the legal status of the so-called Dreamers—undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children—before the government runs out of money at midnight on Friday. The House passed a bill on Thursday that would fund the government through February 16, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell doesn’t appear to have the votes needed to send the measure to the president’s desk.

Here’s the rub: There is a real cost to the federal government—and American taxpayers—as a result of the jockeying on Capitol Hill even when a shutdown doesn’t happen. Interviews with current and former senior-level federal employees involved in planning for shutdowns, as well as outside experts on the federal budget and government management, highlight the vast amount of wasted resources and manpower devoted to preparing for shutdowns.

“It’s like if you were a homeowner but literally every month you had to decide if you were going to move on the first of the month or not,” says Dan Kanninen, a former deputy chief of staff and White House liaison at the Environmental Protection Agency during the Obama administration. “All you’re doing is deciding whether to box stuff up, do you have a moving company, all of that.”

Kanninen worked at the EPA from 2010 to 2012. During that time, he says, the agency operated constantly under the threat of a shutdown. It came within hours of one during the April 2011 standoff in Congress over budget cuts and federal funding for Planned Parenthood.

Federal guidelines require government agencies to prepare for a potential shutdown. Kanninen recalls a mobilization process that began weeks, and sometimes more than a month, in advance. In a recent interview, he described an endless stream of meetings to determine which employees were deemed essential (and thus allowed to keep working during a shutdown) and which employees were deemed non-essential and could be furloughed. There were meetings to decide what to do with laboratories and other EPA research facilities across the country and still more meetings to make sure the agency didn’t miss deadlines on the many lawsuits to which it was a party.

“The fact that Congress would use this brinksmanship strategy all the time, whether on the debt limit or continuing resolution on the budget, meant we were constantly under threat of this happening month by month,” he says.

Looking back, Kanninen estimates that 20 percent of his time and the time of agency leaders was siphoned off into contingency planning in the eight-week period leading up to a possible shutdown. And that didn’t factor in the time lost on the back end of a shutdown threat, having to rev back up a federal agency of 17,000 employees.

“Even without the shutdown,” he says, “there was a cost to taxpayers and to the country.”

Experts who have studied this subject can’t point to a single dollar figure capturing the total cost of shutdown brinksmanship. But case studies and government analyses have attempted to quantify the impact at the agency level. A 2009 Government Accountability Office report examined the effects of governing by continuing resolution—with the possibility of a shutdown ever-present—on six federal agencies. In one instance, the Bureau of Prisons told GAO investigators that uncertainty and delays in funding forced it to pay an additional $5.4 million for a contract to build the McDowell Prison Facility in West Virginia. The Veterans Health Administration estimated that a one-month continuing resolution results in more than $1 million in lost productivity at VA medical facilities and more than $140,000 in additional costs for the VA’s contracting office.

In 2011, Stars and Stripes reported that the Air Force said continuing resolutions and planning for a shutdown would reduce flying training hours by 10 percent. Active-duty military personnel interviewed that same year by Company Command, a publication affiliated with the Army, said the near-shutdown in 2011 caused training exercises to be canceled. “These events are difficult to reschedule because of ranges, space and ammo coordination,” one member of the Texas Army National Guard told Company Command. “Also, we had Soldiers on advanced party whom we had to send home. All in all, the near-shutdown had a pretty substantial impact at all levels.”

Another soldier told Company Command that soldiers he knew “lost a little faith in their elected leaders (i.e., Congress) for not possessing the leadership and loyalty necessary to ensure that something as basic as paying the people who were fighting a war (that they voted to start) was accomplished.”

Philip Joyce, a public policy professor at the University of Maryland and former Congressional Budget Office employee, published a 2012 paper for the IBM Center for the Business of Government that looked at the impact of late appropriations and shutdown threats. Joyce interviewed about 25 current and former federal budget officials and contractors. His conclusion, as he put it in an interview: “It creates a lot of uncertainty, and uncertainty raises the cost of government and compromises the effectiveness of government.” He says, “It’s as simple as all these people spending time right now for the possibility that there might be a government shutdown. That’s completely wasted time you’re never going to get back.”

While Joyce’s research turned up many examples of waste and inefficiency, he also found that careening from one near-shutdown to the next had become normalized inside government agencies, the new modus operandi. “What I found when I was talking to people out there in agencies is they have in effect built into their planning that they’re not going to get an appropriation until at least three months into the fiscal year,” he says. “You can barely even get them to talk about what the damaging effects of that were because it’s so normal.”

Joyce says the government’s ability to hire and keep talented workers suffers from the turbulence of the past decade. “The ultimate result is that people leave,” he says. “And the people who leave are the people who have options, and those are the people you don’t want to leave.”

Officials with the American Federal Government Employees, the union that represents 700,000 federal workers, say morale is another victim of the ever-present prospect of a shutdown. The decision of which employees are essential and non-essential can cause unrest in the workforce, as does the possibility of being furloughed and going for days or weeks without pay. Even if a shutdown doesn’t happen, furlough notices may still be sent out to employees, taking a toll on their emotional wellbeing and morale on the job.

“Just the words ‘furlough,’ ‘shutdown,’ you’re thinking, ‘Oh, I have to put my life on hold,’” says Amad Ali, the executive vice president of an AFGE local that represents Social Security Administration employees in 25 offices throughout Indiana.

AFGE President J. David Cox, who worked at the Department of Veterans Affairs during the 22-day shutdown in December 1995 and January 1996, remembers talking with his wife about the possibility of not getting paid as the holiday season approached. “My wife and I, we had to ask ourselves: ‘Do we buy Christmas presents for our children?'” Cox says.

Cox says the recent instability of federal funding and the possibility of a shutdown have made a mess of the hiring process at a time when agencies like the VA are hurting for talented doctors and other medical staff. “The VA alone has 49,000 vacancies this moment,” he says. “If you’ve got this top doctor now saying they’re coming to work for you and then the VA says we have to wait another 2, 3, 4 weeks because we don’t have enough money, that doctor is going to go somewhere else.”

The potential of a government shutdown may be a giant waste of taxpayer money, but Congress appears to show little interest in changing that. On December 22, after yet another round of full-scale preparations by agencies bracing for a shutdown, lawmakers passed yet another continuing resolution to keep the government open for several weeks. That measure contained enough money to fund the government through this Friday. If the Senate does pass its own continuing resolution, the countdown clock to bureaucratic armageddon begins again.

Philip Joyce, the University of Maryland professor, says it is possible that small-government conservatives see shutdown threats and the resulting dysfunction as a way to achieve their ultimate aim of whittling down the size and scope of government. But he argues that the debate over the role of government should be separate from the simple act of smoothly funding it. “It’s one thing to say that you want to cut the EPA’s budget by 30 percent,” Joyce says. “It’s another thing to make the EPA ineffective by having it limp along from one continuing resolution to another and leaving positions unfilled and not hiring people. When you do that, there’s an insidious impact on the effectiveness of government.”