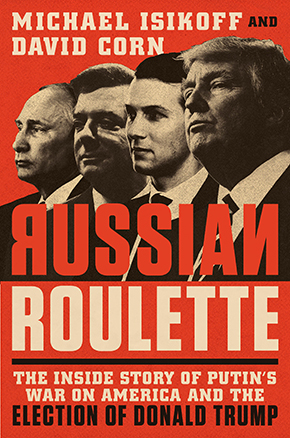

This is the second of two excerpts adapted from Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump (Twelve Books), by Michael Isikoff, chief investigative correspondent for Yahoo News, and David Corn, Washington bureau chief of Mother Jones. The book will be released on March 13.

CIA Director John Brennan was angry. On August 4, 2016, he was on the phone with Alexander Bortnikov, the head of Russia’s FSB, the security service that succeeded the KGB. It was one of the regularly scheduled calls between the two men, with the main subject once more the horrific civil war in Syria. By this point, Brennan had had it with the Russian spy chief. For the past few years, Brennan’s pleas for help in defusing the Syrian crisis had gone nowhere. And after they finished discussing Syria—again with no progress—Brennan addressed two other issues, not on the official agenda.

First, Brennan raised Russia’s harassment of US diplomats—an especially sensitive matter at Langley after an undercover CIA officer had been beaten outside the US embassy in Moscow two months earlier. The continuing mistreatment of US diplomats, Brennan told Bortnikov, was “irresponsible, reckless, intolerable and needed to stop.” And, he pointedly noted, it was Bortnikov’s own FSB “that has been most responsible for this outrageous behavior.”

Then Brennan turned to an even more sensitive issue: Russia’s interference in the American election. Brennan now was aware that at least a year earlier Russian hackers had begun their cyberattack on the Democratic National Committee. We know you’re doing this, Brennan said to the Russian. He pointed out that Americans would be enraged to find out Moscow was seeking to subvert the election and that such an operation could backfire. Brennan warned Bortnikov that if Russia continued this information warfare, there would be a price to pay. He did not specify the consequences.

Bortnikov, as Brennan expected, denied Russia was doing anything to influence the election. This was, he groused, Washington yet again scapegoating Moscow. Brennan repeated his warning. Once more Bortnikov claimed there was no Russian meddling. But, he added, he would inform Russian President Vladimir Putin of Brennan’s comments.

This was the first of several warnings that the Obama administration would send to Moscow. But the question of how forcefully to respond would soon divide the White House staff, pitting the National Security Council’s top analysts for Russia and cyber issues against senior policymakers within the administration. It was a debate that would culminate that summer with a dramatic directive from President Barack Obama’s national security adviser to the NSC staffers developing aggressive proposals to strike back against the Russians: “Stand down.”

At the end of July—not long after WikiLeaks had dumped more than 20,000 stolen DNC emails before the Democrats’ convention—it had become obvious to Brennan that the Russians were mounting an aggressive and wide-ranging effort to interfere in the election. He was also seeing intelligence about contacts and interactions between Russian officials and Americans involved in the Trump campaign. By now, several European intelligence services had reported to the CIA that Russian operatives were reaching out to people within Trump’s circle. And the Australian government had reported to US officials that its top diplomat in the United Kingdom had months earlier been privately told by Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos that Russia had “dirt” on Hillary Clinton. By July 31, the FBI had formally opened a counterintelligence investigation into the Trump’s campaigns ties to Russians, with subinquiries targeting four individuals: Paul Manafort, the campaign chairman, Michael Flynn, the former Defense Intelligence Agency chief who had led the crowd at the Republican convention in chants of “Lock her up!”, Carter Page, a foreign policy adviser who had just given a speech in Moscow, and Papadopoulos.

Brennan spoke with FBI Director James Comey and Admiral Mike Rogers, the head of the NSA, and asked them to dispatch to the CIA their experts to form a working group at Langley that would review the intelligence and figure out the full scope and nature of the Russian operation. Brennan was thinking about the lessons of the 9/11 attack. Al Qaeda had been able to pull off that operation partly because US intelligence agencies—several of which had collected bits of intelligence regarding the plotters before the attack—had not shared the material within the intelligence community. Brennan wanted a process in which NSA, FBI, and CIA experts could freely share with each other the information each agency had on the Russian operation—even the most sensitive information that tended not to be disseminated throughout the full intelligence community.

Brennan realized this was what he would later call “an exceptionally, exceptionally sensitive issue.” Here was an active counterintelligence case—already begun by the FBI—aiming at uncovering and stopping Russian covert activity in the middle of a US presidential campaign. And it included digging into whether it involved Americans in contact with Russia.

While Brennan wrangled the intelligence agencies into a turfcrossing operation that could feed the White House information on the Russian operation, Obama convened a series of meetings to devise a plan for responding to and countering whatever the Russians were up to. The meetings followed the procedure known in the federal government as the interagency process. The general routine was for the deputy chiefs of the relevant government agencies to meet and hammer out options for the principals—that is, the heads of the agencies—and then for the principals to hold a separate (and sometimes parallel) chain of meetings to discuss and perhaps debate before presenting choices to the president.

But for this topic, the protocols were not routine. Usually, when the White House invited the deputies and principals to such meetings, they informed them of the subject at hand and provided “read ahead” memos outlining what was on the agenda. This time, the agency officials just received instructions to show up at the White House at a certain time. No reason given. No memos supplied. “We were only told that a meeting was scheduled and our principal or deputy was expected to attend,” recalled a senior administration official who participated in the sessions. (At the State Department, only a small number of officials were cleared to receive the most sensitive information on the Russian hack; the group included Secretary of State John Kerry; Tony Blinken, the deputy secretary of state; Dan Smith, head of the department’s intelligence bureau; and Jon Finer, Kerry’s chief of staff.)

For the usual interagency sessions, principals and deputies could bring staffers. Not this time. “There were no plus-ones,” an attendee recalled. When the subject of a principals or deputies meeting was a national security matter, the gathering was often held in the Situation Room of the White House. The in-house video feed of the Sit Room—without audio—would be available to national security officials at the White House and elsewhere, and these officials could at least see that a meeting was in progress and who was attending. For the meetings related to the Russian hack, Susan Rice, Obama’s national security adviser, ordered the video feed turned off. She did not want others in the national security establishment to know what was underway, fearing leaks from within the bureaucracy.

Rice would chair the principals’ meetings—which brought together Brennan, Comey, Kerry, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, Defense Secretary Ash Carter, Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, Attorney General Loretta Lynch, and General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—with only a few other White House officials present, including White House chief of staff Denis McDonough, homeland security adviser Lisa Monaco, and Colin Kahl, Vice President Joe Biden’s national security adviser. (Kahl had to insist to Rice that he be allowed to attend so Biden could be kept up to speed.)

Rice’s No. 2, deputy national security adviser Avril Haines, oversaw the deputies’ sessions. White House officials not in the meetings were not told what was being discussed. This even included other NSC staffers—some of whom bristled at being cut out. Often the intelligence material covered in these meetings was not placed in the President’s Daily Brief, the top-secret document presented to the president every morning. Too many people had access to the PDB. “The opsec on this”—the operational security—“was as tight as it could be,” one White House official later said.

As the interagency process began, there was no question on the big picture being drawn up by the analysts and experts assembled by Brennan: Russian state-sponsored hackers were behind the cyberattacks and the release of swiped Democratic material by WikiLeaks, Guccifer 2.0 (an internet persona suspected of being a Russian front), and a website called DCLeaks.com. “They knew who the cutouts were,” one participant later said. “There was not a lot of doubt.” It was not immediately clear, however, how far and wide within the Russian government the effort ran. Was it coming from one or two Russian outfits operating on their own? Or was it being directed from the top and part of a larger project?

The intelligence, at this stage, was also unclear on a central point: Moscow’s primary aim. Was it to sow discord and chaos to delegitimize the US election? Prompting a political crisis in the United States was certainly in keeping with Putin’s overall goal of weakening Western governments. There was another obvious reason for the Russian assault: Putin despised Hillary Clinton, blaming her for the domestic protests that followed the 2011 Russian legislative elections marred by fraud. (At the time, as secretary of state, Clinton had questioned the legitimacy of the elections.) US officials saw the Russian operation as designed at least to weaken Clinton during the election—not necessarily to prevent her from winning. After all, the Russians were as susceptible as any political observers to the conventional wisdom that she was likely to beat Trump. If Clinton, after a chaotic election, staggered across the finish line, bruised and battered, she might well be a damaged president and less able to challenge Putin.

And there was a third possible reason: to help Trump. Did the Russians believe they could influence a national election in the United States and affect the results? At this stage, the intelligence community analysts and officials working on this issue considered this point not yet fully substantiated by the intelligence they possessed. Given Trump’s business dealings with Russians over the years and his long line of puzzling positive remarks about Putin, there seemed ample cause for Putin to desire Trump in the White House. The intelligence experts did believe this could be part of the mix for Moscow: Why not shoot for the moon and see if we can get Trump elected?

“All these potential motives were not mutually exclusive,” a top Obama aide later said.

Obama would be vacationing in Martha’s Vineyard until August 21, and the deputies took his return as an informal deadline for preparing a list of options—sanctions, diplomatic responses, and cyber counterattacks—that could be put in front of the principals and the president.

As these deliberations were underway, more troubling intelligence got reported to the White House: Russian-linked hackers were probing the computers of state election systems, particularly voter registration databases. The first reports to the FBI came from Illinois. In late June, its voter database was targeted in a persistent cyberattack that lasted for weeks. The attackers were using foreign IP addresses, many of which were traced to a Dutch company owned by a heavily tattooed 26-year-old Russian who lived in Siberia. The hackers were relentlessly pinging the Illinois database five times per second, 24 hours a day, and they succeeded in accessing data on up to 200,000 voters. Then there was a similar report from Arizona, where the username and password of a county election official was stolen. The state was forced to shut down its voter registration system for a week. Then in Florida, another attack.

One NSC staffer regularly walked into the office of Michael Daniel, the White House director of cybersecurity, with disturbing updates. “Michael,” he would say, “five more states got popped.” Or four. Or three. At one point, Daniel took a deep breath and told him, “It’s starting to look like every single state has been targeted.”

“I don’t think anybody knew what to make of it,” Jeh Johnson later said. The states selected seemed to be random; his Department of Homeland Security could see no logic to it. If the goal was simply to instigate confusion on Election Day, Johnson figured, whoever was doing this could simply call in a bomb threat. Other administration officials had a darker view and believed that the Russians were deliberately plotting digital manipulations, perhaps with the goal of altering results.

Michael Daniel was worried. He believed the Russians’ ability to fiddle with the national vote count—and swing a national US election to a desired candidate—seemed limited, if not impossible. “We have 3,000 jurisdictions,” Daniel subsequently explained. “You have to pick the county where the race was going to be tight and manipulate the results. That seemed beyond their reach. The Russians were not trying to flip votes. To have that level of precision was not feasible.”

RELATED: A Veteran Spy Has Given the FBI Information Alleging a Russian Operation to Cultivate Donald Trump

But Daniel was focused on another parade of horribles: If hackers could penetrate a state election voter database, they might be able to delete every 10th name. Or flip two digits in a voter’s ID number—so when a voter showed up at the polls, his or her name would not match. The changes could be subtle, not easily discerned. But the potential for disorder on Election Day was immense. The Russians would only have to cause problems in a small number of locations—problems with registration files, vote counting, or other mechanisms—and faith in the overall tally could be questioned. Who knew what would happen then?

Daniel even fretted that the Russians might post online a video of a hacked voting machine. The video would not have to be real to stoke the paranoids of the world and cause a segment of the electorate to suspect—or conclude—that the results could not be trusted. He envisioned Moscow planning to create multiple disruptions on Election Day to call the final counts into question.

The Russian scans, probes, and penetrations of state voting systems changed the top-secret conversations underway. Administration officials now feared the Russians were scheming to infiltrate voting systems to disrupt the election or affect tallies on Election Day. And the consensus among Obama’s top advisers was that potential Russian election tampering was far more dangerous. The Russian hack-and-dump campaign, they generally believed, was unlikely to make the difference in the outcome of the presidential election. (After all, could Trump really beat Clinton?) Yet messing with voting systems could raise questions about the integrity of the election and the results. That was, they thought, the more serious threat.

Weeks earlier, Trump had started claiming that the only way he could lose the election would be if it were “rigged.” With one candidate and his supporters spreading this notion, it would not take many irregularities to spark a full-scale crisis on Election Day.

Obama instructed Johnson to move immediately to shore up the defenses of state election systems. On August 15, Johnson, while in the basement of his parents’ home in upstate New York, held a conference call with secretaries of state and other chief election officials of every state. Without mentioning the Russian cyber intrusions into state systems, he told them there was a need to boost the security of the election infrastructure and offered DHS’s assistance. He raised the possibility of designating election systems as “critical infrastructure”—just like dams and the electrical grid—meaning that a cyberattack could trigger a federal response.

Much to Johnson’s surprise, this move ran into resistance. Many of the state officials—especially from the red states—wanted little, if anything, to do with the DHS. Leading the charge was Brian Kemp, Georgia’s secretary of state, an ambitious, staunchly conservative Republican who feared the hidden hand of the Obama White House. “We don’t need the federal government to take over our voting,” he told Johnson.

Johnson tried to explain that DHS’s cybersecurity experts could help state systems search for vulnerabilities and protect against penetrations. He encouraged them to take basic cybersecurity steps, such as ensuring voting machines were not connected to the internet when voting was underway. And he kept explaining that any federal help would be voluntary for the states. “He must have used the word voluntary 15 times,” recalled a Homeland Security official who was on the call. “But there was a lot of skepticism that revolved around saying, ‘We don’t want Big Brother coming in and running our election process.’ ”

After the call, Johnson and his aides realized encouraging local officials to accept their help was going to be tough. They gave up on the idea of declaring these systems critical infrastructure and instead concluded they would have to keep urging state and local officials to accept their cybersecurity assistance.

Johnson’s interaction with local and state officials was a warning for the White House. If administration officials were going to enlist these election officials to thwart Russian interference in the voting, they would need GOP leaders in Congress to be part of the endeavor and, in a way, vouch for the federal government. Yet they had no idea how difficult that would be.

At the first principals meeting, Brennan had serious news for his colleagues: The most recent intelligence indicated that Putin had ordered or was overseeing the Russian cyber operations targeting the US election. And the intelligence community—sometimes called the IC by denizens of that world—was certain that the Russian operation entailed more than spy services gathering information. It now viewed the Russian action as a full-scale active measure.

This intelligence was so sensitive it had not been put in the President’s Daily Brief. Brennan had informed Obama personally about this, but he did not want this information circulating throughout the national security system.

The other principals were surprised to hear that Putin had a direct hand in the operation and that he would be so bold. It was one thing for Russian intelligence to see what it could get away with; it was quite another for these attacks to be part of a concerted effort from the top of the Kremlin hierarchy.

But a secret source in the Kremlin, who two years earlier had regularly provided information to an American official in the US embassy, had warned then that a massive operation targeting Western democracies was being planned by the Russian government. The development of the Gerasimov doctrine—a strategy for nonmilitary combat named after a top Russian general who had described it in an obscure military journal in 2013—was another indication that full-scale information warfare against the United States was a possibility. And there had been an intelligence report in May noting that a Russian military intelligence officer had bragged of a payback operation that would be Putin’s revenge on Clinton. But these few clues had not led to a consensus at senior government levels that a major Putin-led attack was on the way.

At this point, Obama’s top national security officials were uncertain how to respond. As they would later explain it, any steps they might take-calling out the Russians, imposing sanctions, raising alarms about the penetrations of state systems—could draw greater attention to the issue and maybe even help cause the disorder the Kremlin sought. A high‑profile U.S. government reaction, they worried, could amplify the psychological effects of the Russian attack and help Moscow achieve its end. “There was a concern if we did too much to spin this up into an Obama-Putin face-off, it would help the Russians achieve their objectives,” a participant in the principals meeting later noted. “It would create chaos, help Trump, and hurt Clinton. We had to figure out how to do this in a way so we wouldn’t create an own-goal. We had a strong sense of the Hippocratic Oath: Do no harm.”

RELATED: How a Russian-Linked Shell Company Hired An Ex-Trump Aide to Boost Albania’s Right-Wing Party in DC

A parallel concern for them was how the Obama administration could respond to the Russian attack without appearing too partisan. Obama was actively campaigning for Clinton. Would a tough and vocal reaction be seen as a White House attempt to assist Clinton and stick it to Trump? They worried that if a White House effort to counter Russian meddling came across as a political maneuver, that could compromise the ability of the Department of Homeland Security to work with state and local election officials to make sure the voting system was sound. (Was Obama too worried about being perceived as prejudicial or conniving? “Perhaps there was some overcompensation,” a top Obama aide said later.)

As Obama and his top policymakers saw it, they were stuck with several dilemmas. Inform the public about the Russian attack without triggering widespread unease about the election system. Be pro-active without coming across as partisan and bolstering Trump’s claim the election was a sham. Prevent Putin from further cyber aggression without prompting him to do more. “This was one of the most complex and challenging issues I dealt with in government,” Avril Haines, the NSC’s number two official, who oversaw the deputies meetings, later remarked.

The principals asked the Treasury Department to craft a list of far-reaching economic sanctions. Officials at the State Department began working up diplomatic penalties. And the White House pushed the IC to develop more intelligence on the Russian operation so Obama and his aides could consider whether to publicly call out Moscow.

At this point, a group of NSC officials, committed to a forceful response to Moscow’s intervention, started concocting creative options for cyberattacks that would expand the information war Putin had begun.

Michael Daniel and Celeste Wallander, the National Security Council’s top Russia analyst, were convinced the United States needed to strike back hard against the Russians and make it clear that Moscow had crossed a red line. Words alone wouldn’t do the trick; there had to be consequences. “I wanted to send a signal that we would not tolerate disruptions to our electoral process,” Daniel recalled. His basic argument: “The Russians are going to push as hard as they can until we start pushing back.”

Daniel and Wallander began drafting options for more aggressive responses beyond anything the Obama administration or the US government had ever before contemplated in response to a cyberattack. One proposal was to unleash the NSA to mount a series of far-reaching cyberattacks: to dismantle the Guccifer 2.0 and DCLeaks websites that had been leaking the emails and memos stolen from Democratic targets, to bombard Russian news sites with a wave of automated traffic in a denial-of-service attack that would shut the news sites down, and to launch an attack on the Russian intelligence agencies themselves, seeking to disrupt their command and control modes.

Knowing that Putin was notoriously protective of any information about his family, Wallander suggested targeting Putin himself. She proposed leaking snippets of classified intelligence to reveal the secret bank accounts in Latvia held for Putin’s daughters—a direct poke at the Russian president that would be sure to infuriate him. Wallander also brainstormed ideas with Victoria Nuland, the assistant secretary of state for European affairs and a fellow hard-liner. They drafted other proposals: to dump dirt on Russian websites about Putin’s money, about the girlfriends of top Russian officials, about corruption in Putin’s United Russia party—essentially to give Putin a taste of his own medicine. “We wanted to raise the cost in a manner Putin recognized,” Nuland recalled.

One idea Daniel proposed was unusual: The United States and NATO should publicly announce a giant “cyber exercise” against a mythical Eurasian country, demonstrating that Western nations had it within their power to shut down Russia’s entire civil infrastructure and cripple its economy.

But Wallander and Daniel’s bosses at the White House were not on board. One day in late August, national security adviser Susan Rice called Daniel into her office and demanded he cease and desist from working on the cyber options he was developing. “Don’t get ahead of us,” she warned him. The White House was not prepared to endorse any of these ideas. Daniel and his team in the White House cyber response group were given strict orders: “Stand down.” She told Daniel to “knock it off,” he recalled.

Daniel walked back to his office. “That was one pissed-off national security adviser,” he told one of his aides.

At his morning staff meeting, Daniel matter-of-factly said to his team that it had to stop work on options to counter the Russian attack: “We’ve been told to stand down.” Daniel Prieto, one of Daniel’s top deputies, recalled, “I was incredulous and in disbelief. It took me a moment to process. In my head I was like, ‘Did I hear that correctly?'” Then Prieto spoke up, asking, “Why the hell are we standing down? Michael, can you help us understand?” Daniel informed them that the orders came from both Rice and Monaco. They were concerned that if the options were to leak, it would force Obama to act. “They didn’t want to box the president in,” Prieto subsequently said.

It was a critical moment that, as Prieto saw it, scuttled the chance for a forceful immediate response to the Russian hack—and keenly disappointed the NSC aides who had been developing the options. They were convinced that the president and his top aides didn’t get the stakes. “There was a disconnect between the urgency felt at the staff level” and the views of the president and his senior aides, Prieto later said. When senior officials argued that the issue could be revisited after Election Day, Daniel and his staff intensely disagreed. “No—the longer you wait, it diminishes your effectiveness. If you’re in a street fight, you have to hit back,” Prieto remarked.

Obama and his top aides did view the challenge at hand differently than the NSC staffers. “The first-order objective directed by President Obama,” McDonough recalled, “was to protect the integrity of election.” Confronting Putin was necessary, Obama believed, but not if it risked blowing up the election. He wanted to make sure whatever action was taken would not lead to a political crisis at home—and with Trump the possibility for that was great. The nation had had more than 200 years of elections and peaceful transitions of power. Obama didn’t want that to end on his watch.

By now, the principals were into the nitty-gritty, discussing in the Sit Room the specifics of how to respond. They were not overly concerned about Moscow’s influence campaign to shape voter attitudes. The key question was precisely how to thwart further Russian meddling that could undermine the mechanics of the election. Strong sanctions? Other punishments?

The principals did discuss cyber responses. The prospect of hitting back with cyber caused trepidation within the deputies and principals meetings. The United States was telling Russia this sort of meddling was unacceptable. If Washington engaged in the same type of covert combat, some of the principals believed, Washington’s demand would mean nothing, and there could be an escalation in cyber warfare. There were concerns that the United States would have more to lose in all-out cyberwar.

“If we got into a tit-for-tat on cyber with the Russians, it would not be to our advantage,” a participant later remarked. “They could do more to damage us in a cyber war or have a greater impact.” In one of the meetings, Clapper said he was worried that Russia might respond with cyberattacks against America’s critical infrastructure—and possibly shut down the electrical grid.

The State Department had worked up its own traditional punishments: booting Russian diplomats—and spies—out of the United States and shutting down Russian facilities on American soil. And Treasury had drafted a series of economic sanctions that included massive assaults on Putin’s economy, such as targeting Russia’s military industries and cutting off Russia from the global financial system. One proposal called for imposing the same sorts of sanctions as had been placed on Iran: any entity that did business with Russian banks would not be allowed to do business with US financial institutions. But the intelligence community warned that if the United States responded with a massive response of any kind, Putin would see it as an attempt at regime change. “This could lead to a nuclear escalation,” a top Obama aide later said, speaking metaphorically.

After two weeks or so of deliberations, the White House put these options on hold. Instead, Obama and his aides came up with a different plan. First, DHS would keep trying to work with the state voting systems. For that to succeed, the administration needed buy-in from congressional Republicans. So Obama would reach out to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and House Speaker Paul Ryan to try to deliver a bipartisan and public message that the Russian threat to the election was serious and that local officials should collaborate with the feds to protect the electoral infrastructure.

Obama and the principals also decided that the US government would have to issue a public statement calling out Russia for having already secretly messed with the 2016 campaign. But even this seemed a difficult task fraught with potential problems. Obama and his top aides believed that if the president himself issued such a message, Trump and the Republicans would accuse him of exploiting intelligence—or making up intelligence—to help Clinton. The declaration would have to come from the intelligence community. The intelligence community was instructed to start crafting a statement. In the meantime, Obama would continue to say nothing publicly about the most serious information warfare attack ever launched against the United States.

Most of all, Obama and his aides had to figure out how to ensure the Russians ceased their meddling immediately. They came up with an answer that would frustrate the NSC hawks, who believed Obama and his senior advisers were tying themselves in knots and looking for reasons not to act. The president would privately warn Putin and vow overwhelming retaliation for any further intervention in the election. This, they thought, could more likely dissuade Putin than hitting back at this moment. That is, they believed the threat of action would be more effective than actually taking action.

A meeting of the G-20 was scheduled for the first week in September in China. Obama and Putin would both be attending. Obama, according to this plan, would confront Putin and issue a powerful threat that supposedly would convince Russia to back off. Obama would do so without spelling out for Putin the precise damage he would inflict on Russia. “An unspecified threat would be far more potent than Putin knowing what we would do,” one of the principals later said. “Let his imagination run wild. That would be far more effective, we thought, than freezing this or that person’s assets.” But the essence of the message would be that if Putin did not stop, the United States would impose sanctions to crater Russia’s economy.

Obama and his aides were confident the intelligence community could track any new Russian efforts to penetrate the election infrastructure. If the IC detected new attempts, Obama then could quickly slam Russia with sanctions or other retribution. But, the principals agreed, for this plan—no action now, but possible consequences later—to work, the president had to be ready to pull the trigger.

Obama threatened—but never did pull the trigger. In early September, during the G-20 summit in Hangzhou, China, the president privately confronted Putin in what a senior White House official described as a “candid” and “blunt” talk. The president informed his aides he had delivered the message he and his advisers had crafted: We know what you’re doing, if you don’t cut it out. We will impose onerous and unprecedented penalties. One senior US government official briefed on the meeting was told that the president said to Putin in effect, “You fuck with us over the election and we’ll crash your economy.”

But Putin simply denied everything to Obama—and, as he had done before, blamed the United States for interfering in Russian politics. And if Obama was tough in private, publicly he played the statesman. Asked at a post-summit news conference about Russia’s hacking of the election, the president spoke in generalities—and insisted the United States did not want a blowup over the issue. “We’ve had problems with cyber intrusions from Russia in the past, from other counties in the past,” he said. “Our goal is not to suddenly in the cyber arena duplicate a cycle escalation that we saw when it comes to other arms races in the past, but rather to start instituting some norms so that everybody’s acting responsibly.”

White House officials believed for a while that Obama’s warning had some impact: They saw no further evidence of Russia cyber intrusions into state election systems. But as they would later acknowledge, they largely missed Russia’s information warfare campaign aimed at influencing the election—the inflammatory Facebook ads and Twitter bots created by an army of Russian trolls working for the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg.

On October 7, the Obama administration finally went public, releasing a statement from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Department of Homeland Security that called out the Russians for their efforts to “interfere with the U.S. election process,” saying that “only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.” But for some in the Clinton campaign and within the White House itself, it was too little, too late. Wallander, the NSC Russia specialist who had pushed for a more aggressive response, thought the October 7 statement was largely irrelevant. “The Russians don’t care what we say,” she later noted. “They care what we do.” (The same day the statement came out, WikiLeaks began its monthlong posting of tens of thousands of emails Russian hackers had stolen from John Podesta, the CEO of the Clinton campaign.)

In the end, some Obama officials thought they had played a bad hand the best they could and had succeeded in preventing a Russian disruption of Election Day. Others would ruefully conclude that they may have blown it and not done enough. Nearly two months after the election, Obama did impose sanctions on Moscow for its meddling in the election—shutting down two Russian facilities in the United States suspected of being used for intelligence operations and booting out 35 Russian diplomats and spies. The impact of these moves was questionable. Rice would come to believe it was reasonable to think that the administration should have gone further. As one senior official lamented, “Maybe we should have whacked them more.”

Image credits: Klimentyev Mikhail/TASS/ZUMA; Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP; John Locher/AP