Danny Fields discovered and signed the Stooges and MC5. He worked with the Doors and rubbed elbows with the Velvet Underground. That famous John Lennon quote about the Beatles being bigger than Jesus? That was largely Danny’s doing, running Lennon’s quote in the teen magazine he edited, Datebook. He’s been in the thick of some of the headiest moments of rock ‘n’ roll, including working at the Ramones first manager from 1975 to 1977. During his time with them, he almost always had a camera. His new book, My Ramones, brings you backstage during the gestational period of one of the first and finest punk bands.

Dee Dee, Johnny and Tommy Ramone enjoying thumbing through bins of vinyl at the now vanished Free Being Records on Second Avenue.

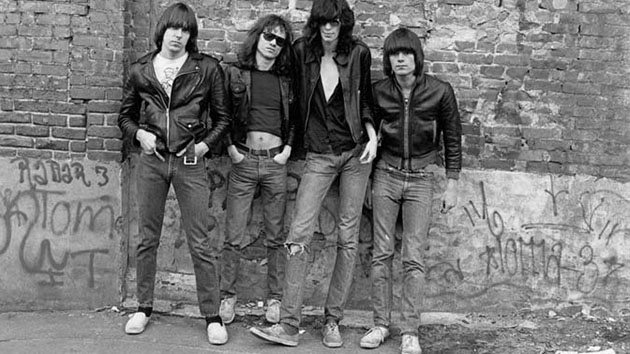

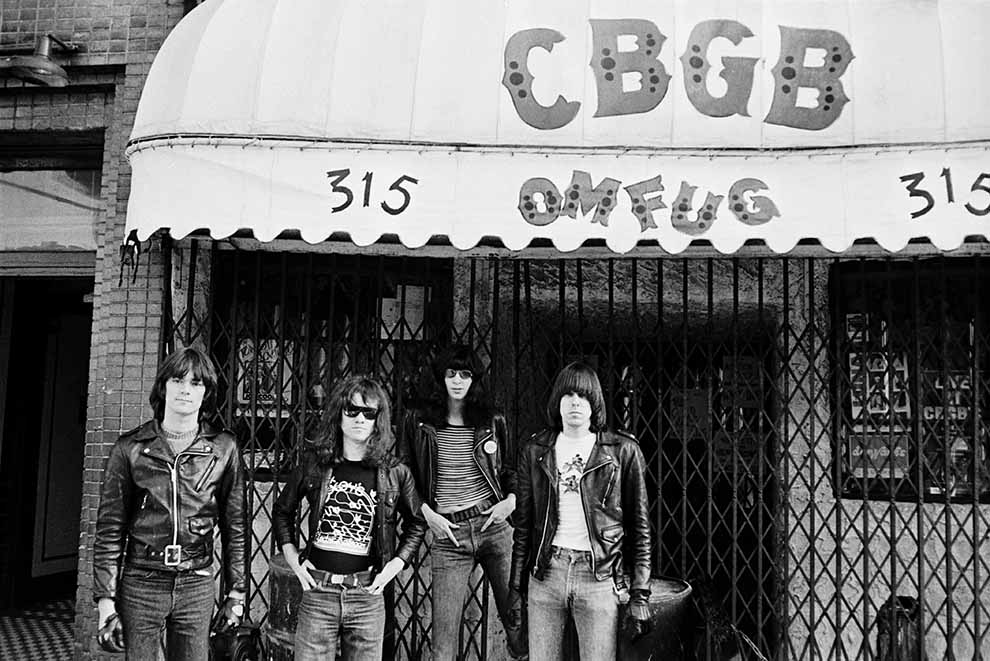

The Ramones taking pictures for Rock Scene magazine in front of CBGB OMFUG (Country, Bluegrass, Blues and Other Music For Uplifting Gormandizers).

Even though he never considered himself as a professional photographer, Fields shot regularly for 16 Magazine, which he edited, and funneled images of New York bands to Rock Scene, a photo-heavy music magazine run by his friend Lisa Robinson. In all, he shot about 100 rolls of the Ramones. “I wish I had more,” he says. About 270 of those photos make up this book. First published in England in a limited edition, My Ramones is finally getting a proper stateside release thanks to Reel Art Press.

“It was never available in the United States or Latin America,” Fields says about the reprinting of the book, first published by London-based First Third Books. “It was available online, but you couldn’t walk into a bookstore, flip through it and say, ‘I want this!'”

I had the pleasure to talk to Danny about his years managing and photographing the Ramones.

All photos by Danny Fields, courtesy of Reel Art Press.

Mother Jones: Why did you start photographing the Ramones?

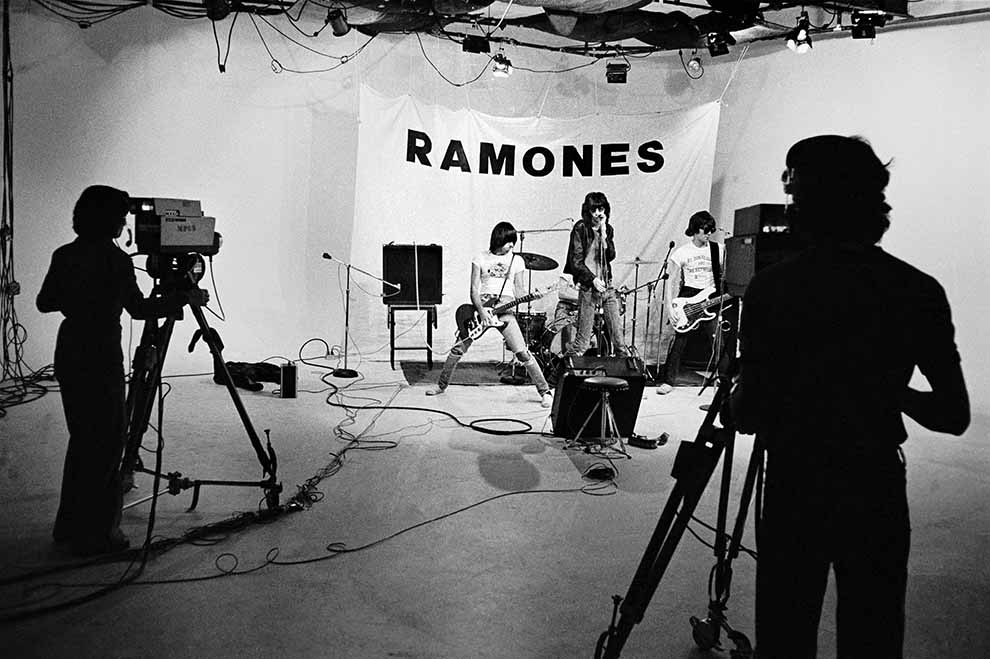

Danny Fields: Well, they sure looked good, as a brand, which they had in mind from the beginning. I was happy to participate in the exposure, because they were perfect—as a band and a brand. I was at the recording studio but I had nothing to do here. I had never been somewhere where I had so little to do. So I took out my camera. I thought it was a moment anyone would want for a scrapbook or autobiographical memoir, from their point of view. Of course they would want this memorialized. You can’t say it, but you think, “Something historical is happening. It should be recorded. I am part of it. They’re my guys, they’re making their first album. My god! It’s legitimate.” You would do that at a family reunion. This why people take pictures of things. Except I had a Nikon with a 85 and a 35mm lens, real film. I worked for 16 Magazine then. I would take a lot of pictures for them.

It was something I thought should be done. No professional photographer would have been allowed into the recording session of a very perfectionist young band. Only me, I was the only one who could do it. Everyone else had something legitimate to do: twirling dials, putting lights up and taping wires to the floor. And when they got the wonderful burst of fame, people were wanting to take pictures of them, so I would say, “If someone wants to do it, line yourselves up, get the right face on, get it to the camera. Let’s try a few of these.” And they did. They were so natural.

MJ: It was like they were practicing with you.

DF: Yeah, it was like practice, but you know, they just couldn’t do a bad picture. They had a sense of always facing an audience, whether that audience was the photographer or the potential audience on the other side of the lens. They just knew how to do it. They lined up perfectly. They compensated for the enormous height in height between Tommy, the drummer, and Joey, the lead singer. Somehow Tommy would always find a brick in the wall he could hook his heel on. Joey would stoop. They just lined up so their heads are virtually on the same level. They were intuitive about that.

Ramones first video shoot. The video contained eight songs in 17-and-a-half minutes and has never been officially released.

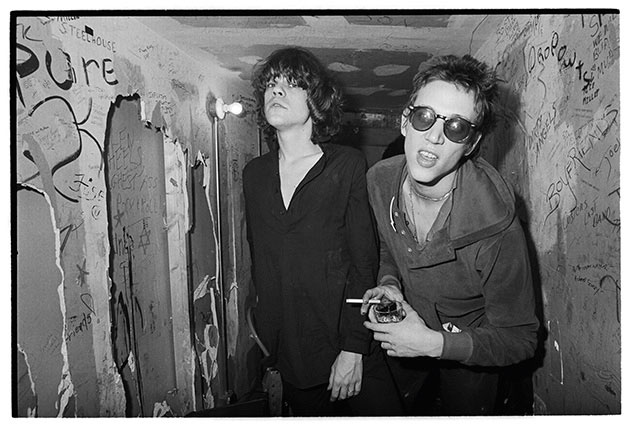

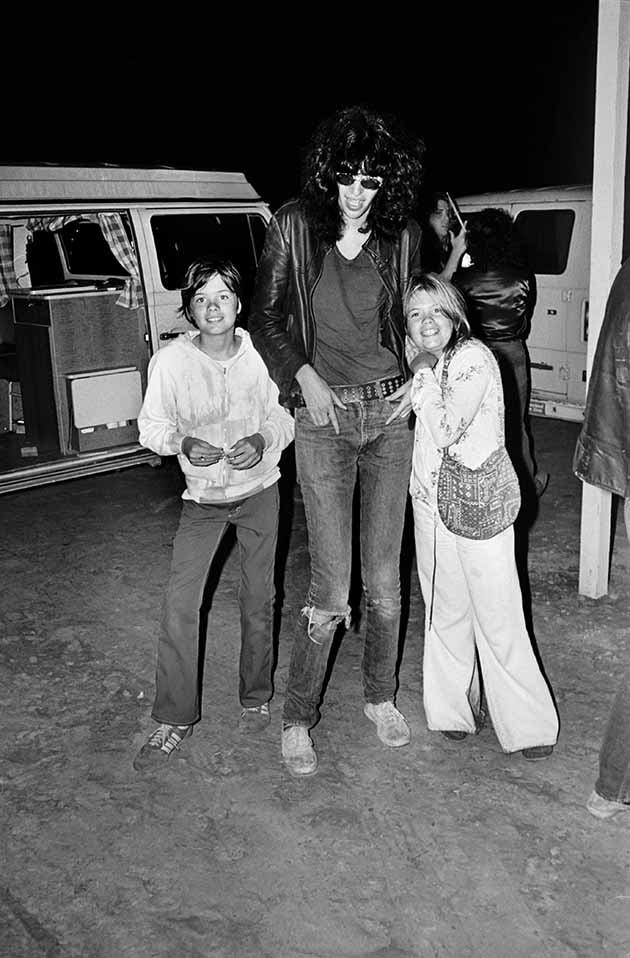

Joey and fans after the first Ramones appearance in San Francisco.

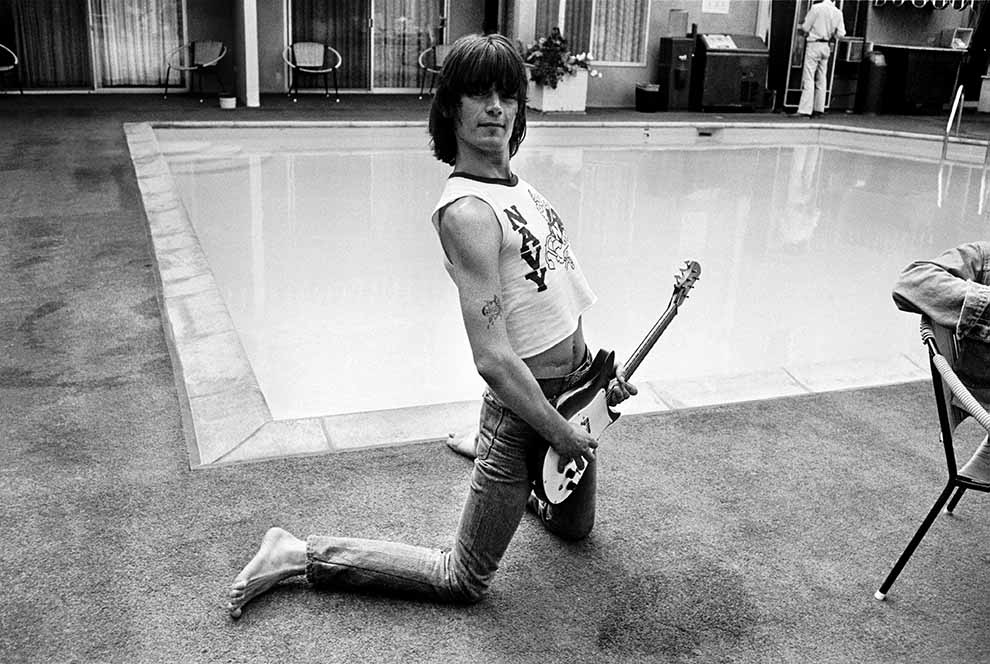

Dee Dee poolside with his spare Rickenbacker guitar.

MJ: Did they ever get tired of you taking pictures of them?

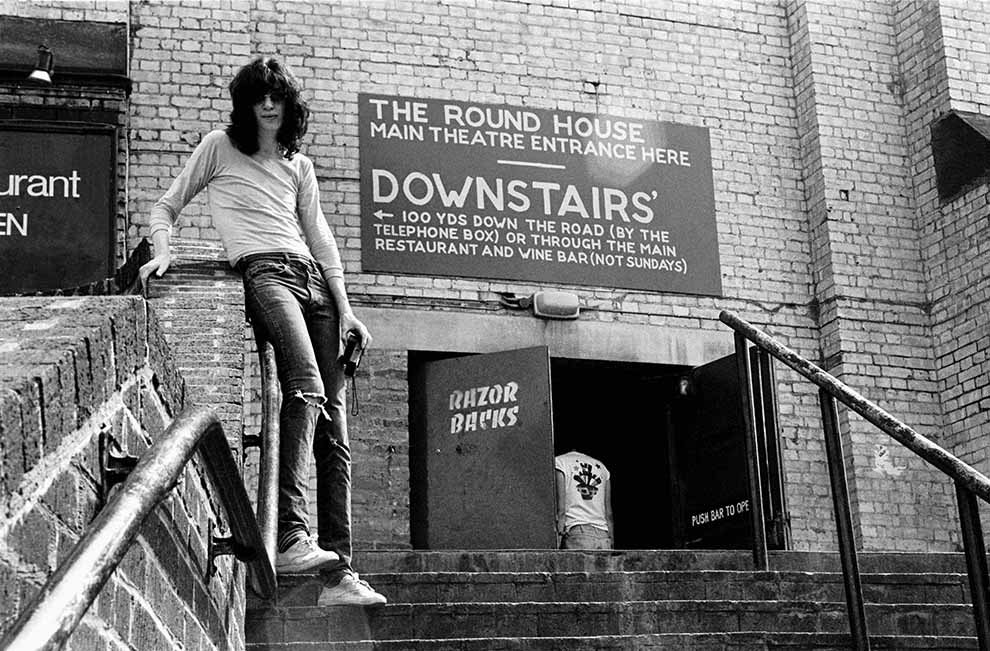

DF: It would be on film if they did. It was the opposite. Joey knew I was there and he gave me a picture. You can see it in any picture where he’s looking into the camera. I didn’t say, “Hey Joey, let’s take a picture of you on top of that staircase outside the Roundhouse.” I was just walking by and would have the camera out. I saw him and he dove into that. That beautiful silhouette of a pose, so skeletal, architectural. He sees me with a camera and gives me a shot. It’ll be in Rock Scene, so it makes it better. He’s just as good as he is, which is Joey Ramone.

Another thing is, they knew if it had been a bad picture, like if someone had a piece of spaghetti hanging out of their mouth or something, I’m not gonna let it go public. I’m the manager! So there was that trust. They trust me. I can read them. The pictures in the dressing room where nobody is supposed to be with a camera, I can do that, I’m just Danny. I can get my pictures and leave you guys to fight or go over the set list or something like that. Just let me get my pictures. I could be alone with them in the locker room and they look candid because I become part of the atmosphere, the layout, part of the catering. There are the glasses of water, the towels and whatever and there’s Danny with a camera. No one ever said, “Not now.”

Ramones perform at the Club in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

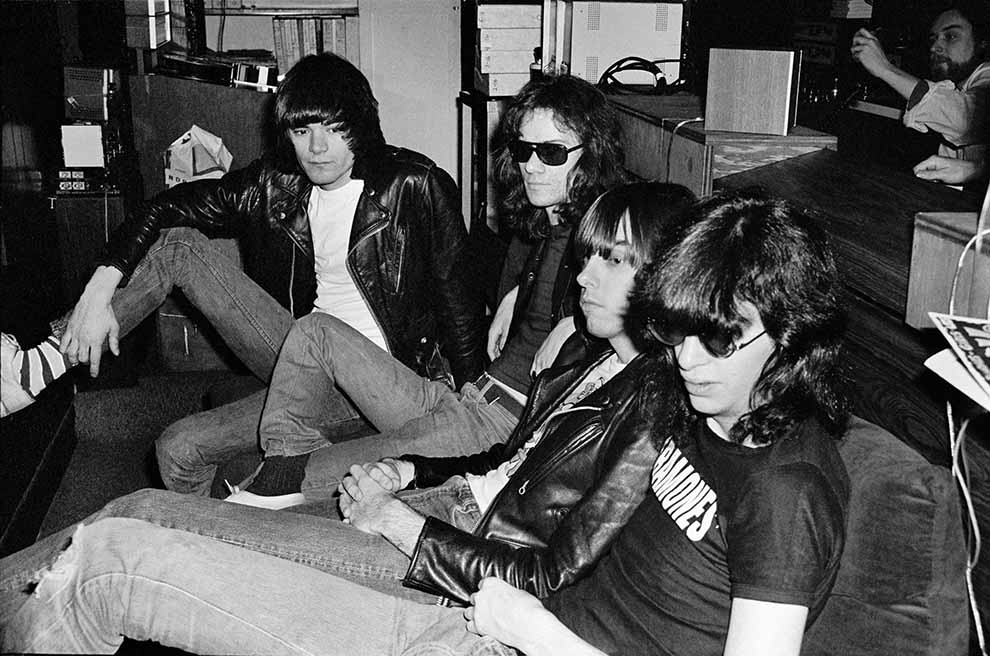

Recording Ramones, the first album.

Joey doing vocals for the first album.

MJ: Going back to what you said about the exposure of the band and the brand, did you work with Arturo Vega on visuals for the band in the early days?

DF: Well, no. We complimented each other and of course he did far more work for the visuals. He designed things. He did the lighting. I don’t go out of my way to make it understood he’s the 5th Ramone, but he is a member of what they’re doing, a creator and inventor of visual aspect of the whole project, much more than I. If these pictures hadn’t been taken, there wouldn’t have been a big difference in their career. I didn’t want to say that much about Arturo. My feeling is, if you care that about this band, it should be evident. If not, then it’s okay. Here are fun pictures of the four of them. And Arturo had a great deal to do with that.

Joey at the Roundhouse, on tour in England.

Ramones live at Phase V, a club in New Jersey.

Ramones during a walking tour of early morning London.

MJ: Did you photograph any other bands you worked with, before or after the Ramones, like the Stooges?

DF: I wish I had. I didn’t have confidence—or access. Photographing Iggy [Pop], I should’ve photographed the whole band. I just have a few Polaroids. I did get one night at Max’s [Kansas City] with Iggy, a couple of years after I had worked with him. They were great photos. All taken one night, one show upstairs at Max’s Kansas City. It’s five rolls. I’m proud of that.

MJ: What about after managing the Ramones? Did you keep shooting?

DF: I stayed away from working with bands. My next job after that was editor of a country music magazine. I would not dare take pictures of Waylon Jennings. Loretta [Lynn]? No, no. I didn’t do any pictures in those days. Except I did take a lot at the Country Music Awards Dinner, like five rolls of film. It was so amazing. The people there! In 1981 I think. It was a different culture, different civilization. Everything was different—the hair—it was just so different. A different world.

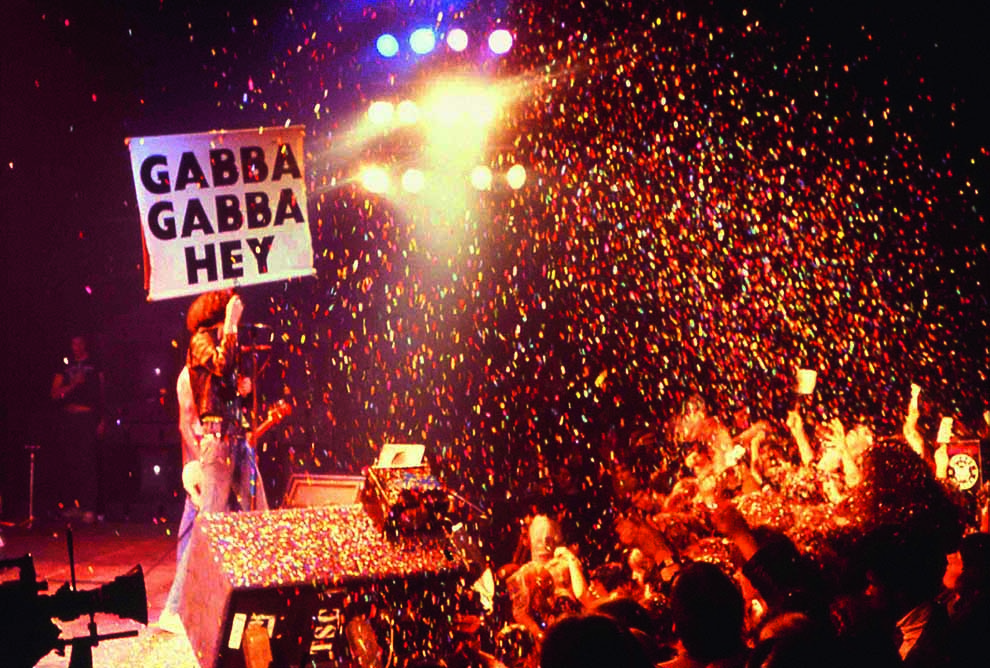

Ramones in 1977, playing a festive New Year’s concert at London’s Rainbow Theatre.