Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Disinformation is becoming increasingly widespread—and troubling. From Russian attempts to influence the 2016 elections to Facebook’s most recent revelation of a coordinated disinformation campaign ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, we’re seeing more and more instances of disinformation cropping up in our social media feeds.

Earlier this year, we asked you to help shape our reporting on disinformation: What did you want to know about disinformation and how it works? Hundreds of you wrote back with questions about the issue: what it is, how to spot it, and effective ways to fight back.

Mother Jones talked to five different experts to help answer your questions. Here’s what you wanted to know:

What is disinformation?

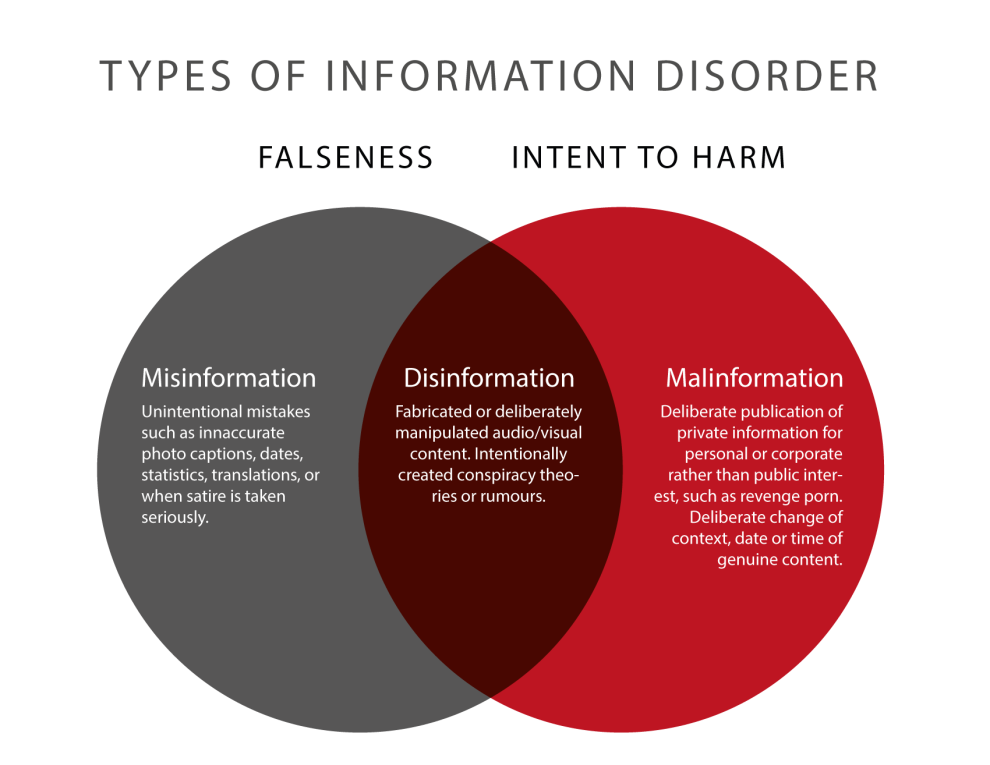

Disinformation is false information that is deliberately created with the intent to mislead someone or cause harm. It falls under the larger umbrella of misinformation, which is defined as any kind of false information.

Claire Wardle, the executive director of First Draft, a project of the Harvard Kennedy’s Shorenstein Center, created a taxonomy for understanding the different types of mis- and disinformation, and breaks it out in this helpful chart here.

It’s important to note, however, that it’s often really hard—and, at times, impossible—to figure out the intent behind a piece of information; the reasons can be complex, and the intent can even shift over time. So generally, it’s helpful to classify something as misinformation first.

How do I spot it?

Disinformation can take any shape or form, whether it’s a false article masquerading as real news, a viral meme, a video, tweet or Facebook post, or even an audio message. That can make it tricky to spot, but most of these posts share a common characteristic: They’re designed to make you react.

“Misinformation typically tries to pull upon whatever emotional heart strings and vulnerabilities you have to try to make you share it,” says Daniel Funke, a reporter at the Poynter Institute who covers fact-checking and misinformation. That’s why it’s not surprising, for instance, that many of the 2016 Russian disinformation campaign posts and ads focused on divisive political issues in the US, such as immigration and gun control.

If you encounter something that elicits a strong reaction, Funke recommends doing a gut check before going to any kind of verification tool. If something feels just too good to be true, it probably is. Wardle at First Draft similarly suggests cultivating more emotional skepticism towards the information we consume. “We tend to think that we have rational relationships to information, but we don’t. We have emotional relationships to information, which is why the most effective disinformation draws on our underlying fears and world views,” she says. “If a piece of information makes you feel scared, angry, disproportionately upset, or even smug, then it’s worth doing additional checks or slowing down before re-sharing it. We’re less likely to be critical of information that reinforces our worldview or taps into our deep-seated emotional responses.”

What should I do once I spot a piece of misinformation?

First of all, don’t share it. That’s one of the biggest, most helpful things you can do to stop the spread of misinformation. Because so much misinformation is intended to get you to share, don’t fall for the trap.

Then, verify the piece. Do a quick Google search on the story: Has Snopes or PolitiFact debunked it? Are any trusted news outlets reporting the same information? What’s the original source of this information and its context? If the original source seems unfamiliar or fishy, investigate the source: Look it up elsewhere—what do other outlets say about it? Does it have a Wikipedia page? This can help you suss out whether the organization has a history of bias or spreading misinformation.

If it’s an image or meme, do a reverse Google image search—oftentimes images are taken out of context or manipulated to create memes, and an image search can help you find the original source. You’ll often be able to find out if something is true or false fairly quickly. Protest signs, church billboards, as well as nature and disaster photos are some of the most commonly manipulated images.

You can also check the comments—has anyone else said this is wrong or offered clarification? Sometimes the creator of a meme—such as this one about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—and subsequent commenters will note that it’s intended as satire or parody. However, the meme itself often ends up being shared without context—and interpreted as real. (If you’re looking for more verification techniques, check out our list of resources at the end of this article!)

Finally, correct the record. If you see someone sharing something that’s incorrect, tell them—and do it publicly. Don’t let the information spread even further or get shared by more people. If the information violates a platform’s community standards, also consider reporting it.

Don’t wait, either. “Time is really of the essence,” says Poynter’s Funke. Information can go viral so quickly that if you decide to wait a day or two, it might already be too late.

What’s the best way to communicate to someone that they’re sharing misinformation?

The number one rule is to be civil. If you see someone sharing something false, try and acknowledge where they’re coming from. Post a link that shows evidence for why the information isn’t true. Experts recommend linking to a fact-checking site or a more neutral, non-partisan source, rather than your favorite blog or website. Fact-checking sites such as Snopes show you the origin of a hoax—linking to a site like this can help someone understand on their own how the information was manipulated. (And while you might not want to get into a tiff with your friends or family, research has shown that, at least on Twitter, users are actually more likely to accept corrections from people they know than from strangers.)

If you can, try and foster a dialogue with the person. You can acknowledge that it’s easy to fall for misinformation, recommends Peter Adams, head of the education team at the News Literacy Project, a nonprofit that helps students develop digital media literacy. “We’re all hardwired to trust our senses and respond to our emotions, and it can be challenging to fight those impulses,” says Adams. “Sharing something false doesn’t make someone foolish or stupid, it just means they got tricked.”

Oftentimes people share something because they identify with it or because they want it to be true, says Wardle, so just telling someone they’re wrong can cause them to even further double down on their beliefs. Ask them why they believe a certain piece of information, or how they came to their conclusions. A meta-analysis of debunking studies found that the more you can help someone create their own counterarguments, the more likely they are to accept a correction or change their minds.

Finally, it’s also important not to just correct false information, but to replace false narratives with correct ones. “One of the reasons conspiracy theories are so powerful is because [they] are powerful narratives—and our brains love strong and emotional narratives.” says Wardle. These narratives can be so strongly imprinted in our minds that just hearing something is wrong or reading a list of facts doesn’t do enough to stop us from believing it. “When you tell your brain something isn’t true, it’s kind of left with a hole—and it doesn’t know how to fill it,” says Wardle. Instead, you need to provide a counter-message or a new narrative. Rather than say, “Obama isn’t Muslim,” for instance, it’s better to say, “Obama is Christian.”

Something looks fishy to me but I’m having a hard time verifying whether it’s true or false. What should I do?

One important thing to keep in mind is that disinformation campaigns don’t always involve easily verifiable facts. Rather, as we’ve seen recently on Facebook, disinformation can take the form of a false group posting actual news articles, creating events, or trying to push particular ideas or viewpoints.

Many disinformation campaigns aren’t just aimed at spreading misinformation; they’re also trying to propagate certain messages—often in order to sow division, says Becca Lewis, a researcher at Data & Society, a think tank that studies the impact of technology on social and cultural issues. “Sometimes those messages are completely debunk-able, but a lot of times, they’re just racist or sexist, or they’re just attempting to exploit differences or fears,” says Lewis. Far-right groups, for instance, often try to flood social media platforms or other spheres with memes, hashtags, and false conspiracy theories that support their views. When their campaigns garner enough attention or outrage that it’s picked up by the media—even if it’s just to be debunked— those ideas spread even further.

Though technology platforms and news sources have a bigger role to play in stemming these kinds of messages, individuals can take action as well. Lewis recommends just being aware of these tactics: Watch out for posts that emphasize a certain ideology or political belief, in addition to being inaccurate. And recognize that this kind of disinformation can appear in a variety of places—on your social media feeds, on personal Facebook groups, and in the media.

Adams, of the News Literacy Project recommends developing an “internal system of red flags” for suspicious content or accounts. Consider looking at when an account was created or its posting history. Does the account post at strange times, despite where it says it’s located? If the account uses an image, can you do a reverse Google image search to see if it’s real? “I think a general disposition of skepticism towards authenticity and identity online goes a long way,” says Adams. (And if you want to know how to spot a Russian bot on Twitter, we’ve also got you covered.)

What can I do to combat misinformation and disinformation?

Experts generally agree that in order to tackle disinformation, both technology companies and media outlets need to play a role in stemming the flow of information. Companies such as Facebook and Twitter in particular could make it harder for many of these bad actors to gain a platform, says Lewis of Data & Society.

But there’s still a lot that you can do individually. Wardle advocates that everyone take far more responsibility for the content they put online. “If we don’t take responsibility and just throw our hands up and say, well, there’s nothing we can do, my fear is that we then just all say: ‘we can’t trust any information anymore,’ and I don’t think that’s good for democracy,” she says. We can all do our part to create a better information environment. Check before you share.

And when you decide to share something, consider what you’re sharing—and if that’s the best source of information. “You don’t have to stick with the source that social media feeds you,” says Mike Caulfield, head of the digital polarization initiative for the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. “Instead of thinking about posting or not posting, tweeting or not tweeting, ask yourself: Can I find a better story? Can I tweet it with some more important context?”

I want to learn more about how to verify information and this topic in general. Where can I go?

We’re so glad you asked! Here’s a handy list of resources on verification, misinformation, and news literacy, suggested by our experts:

- First Draft News, – resources on understanding misinformation, including a free one-hour course on verification tools.

- The Week in Fact-Checking – Poynter’s roundup of news on fact-checking and misinformation.

- Factcheckingday.com – resources on fact-checking.

- The News Literacy Project – resources on teaching news literacy geared for educators.

- Online Verification Skills – a video series on some basic fact-checking techniques.

- A list of tools and resources from Poynter’s Daniel Funke—good for doing deeper dives.

OK, I’m seeing some strange things in my feeds. How can I tell you about it?

We definitely want to hear about anything suspicious—share what you’re seeing in the form below or you can email us screenshots at talk@motherjones.com.