A turf soccer field at the Karnes family detention center in Texas, where Alejandra and Graciela were separated in April.Eric Gay/AP

On April 20, Alejandra and her two-year-old daughter were taken into a small room at the Karnes family detention center in South Texas. Officials working at the center said they had good news and bad news. Alejandra, a 20-year-old from Honduras who had been detained after crossing the border with her daughter, asked for the good news first.

One of the officials told her that her she had passed her interview establishing that she had reason to fear for her safety in Honduras, meaning that her asylum claim could move forward. “But the bad news is that we have to separate you from you from your daughter,” the official said, according to Alejandra. She was told that two people would arrive at 7:30 the next morning to take her daughter, Graciela. The officials didn’t say where Graciela would be going. Why were they taking her? Alejandra asked. Because you have to see a judge, they said.

“I don’t want to see a judge,” she replied. “I want to be with my daughter.”

That night, Alejandra says she cried and prayed that it would all prove to be a nightmare. But the next morning, two people arrived as promised. As they took Graciela away, she cried and reached out for her mother. “And I couldn’t do anything,” Alejandra recalls, speaking in Spanish. (Mother Jones agreed to identify Alejandra and Graciela by pseudonyms to protect their anonymity.)

As her daughter screamed outside the room, Alejandra began to cry. She asked a guard why her daughter was being taken and got the same response: You need to see a judge. She had lost her daughter and had no idea why.

The story of Alejandra and Graciela’s separation is not the story of the more than 2,000 families who were split under the “zero tolerance” initiative carried out this spring. Instead, it represents another, less common mechanism for the administration to separate migrant families with little oversight when it believes parents pose a safety risk.

Zero tolerance, which President Donald Trump abandoned in June, separated families by prosecuting parents for illegally entering the United States. Those parents were transferred to US Immigration Customs and Enforcement, which had no plan for reuniting them with their children.

When Alejandra and Graciela were detained for crossing the border without authorization in April, zero tolerance had not yet begun, and Alejandra was not prosecuted. Instead, after being caught near El Paso, Texas, she and her daughter were transferred to Karnes. There, she went though the “credible fear” interview that US Citizenship and Immigration Services, the division of the Department of Homeland Security that handles legal immigration, uses to determine whether migrants risk persecution if they are deported. Alejandra said in the interview that she was fleeing an abusive partner who belonged to a gang in Honduras. She passed the interview, but a USCIS asylum officer concluded that she was a potential “security risk” and might be ineligible for asylum, even though she says was never involved with her partner’s gang.

USCIS’s security risk determinations reflect people’s potential eligibility for asylum, not their ability to care for a child. Yet Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the DHS agency that manages family detention centers, appears to have used that determination as the basis for separating Alejandra and Graciela while Alejandra awaited a hearing before an immigration judge on her asylum claim.

Adelina Pruneda, an ICE spokeswoman, said in a statement, “Due to ongoing litigation, ICE is unable to provide any details on this matter.” When asked which litigation she was referring to, Pruneda wrote, “The information ICE provided is the only information we are releasing.”

Kathrine Russell, an attorney at the Texas legal aid group RAICES, says she has worked with five mothers since May who were separated at family detention centers. She says all of them passed their credible fear interviews and believes most were separated based on information they disclosed in the interviews. As with Alejandra, ICE did not initially say why it was separating them from their children.

The cases highlight the opaque process ICE uses to separate parents that it believes pose a safety risk to their children or others at family detention centers. Manoj Govindaiah, the director of family detention services for RAICES, says the separations at detention centers appear to be “very arbitrary and without any transparency.” Govindaiah says some parents USCIS considers security risks have remained with their kids, raising further questions about how ICE is making its separation decisions.

Once a family has been separated, it is extremely difficult for detained parents to contest the decision—even when they are lucky enough to find an attorney willing to take their case. “In any other judicial system, the government cannot just take away your kid,” Govindaiah says. “You have to be able to go in front of a judge and get an explanation as to why your child has been taken away and be able to fight to get your child back. And yet here, there’s basically no ability to do that.”

The Obama administration also separated parents it believed posed a risk to their children, and it is not clear if the separations have become more common since Trump took office. But Robert Carey, who led the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement from March 2015 to January 2017, said in a September court declaration that “very young children were rarely separated from their accompanying parents on the basis of the parents’ criminal histories.” He added, “I can only remember one instance where a child under five years of age was separated from his or her parent because of the parent’s alleged criminal conduct, and that was an instance where the parent allegedly was involved in sex trafficking their own child.”

Advocates say that separation may be necessary in rare cases, but they are particularly concerned about how that power could be used by a president who embraced family separation as a way to deter migrants. Compared to the thousands of families who were separated under zero tolerance, the numbers here are much smaller, although immigrant advocates are concerned that immigration lawyers may not be aware of every case. Erica Schommer, an immigration law professor at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio who represented Alejandra in Texas, says, “I just wonder how many parents are detained somewhere in an adult detention center who have no idea why they’re not with their child.”

Without her daughter, Alejandra was transferred from Karnes to the nearby Pearsall detention center, an ICE facility for adults outside San Antonio. Schommer met with her in a windowless visitation room about three days later. Alejandra was sobbing and still had no idea where her case was headed. Schommer was surprised to learn that Alejandra was separated after passing her credible fear interview, something she’d never witnessed in more than a decade practicing immigration law in Texas. “Who made the [separation] decision, why it was made, we had no idea,” she says.

They had only secondhand information to go on. Unaccompanied minors are assigned case workers by the Department of Health and Human Services, and Graciela’s case worker had told Alejandra’s brother-in-law that the government had concerns about gang involvement. “She was very upset about that because, of course, she has no gang involvement,” Schommer says.

Alejandra laughed when I asked her if there was anything to the allegations of gang ties. “My family is all Christian,” she said. “No one has ever had problems with the police, much less me.” She had learned that Graciela’s father, whom she had lived with but did not marry, was involved with a gang after her daughter was born, and that was one of the reasons she fled to the United States. He had physically abused her in the past—sometimes in front of Graciela—and she believed he would find her if she moved in with her mom in Honduras.

In March, she told her partner that she was leaving. “OK, go,” she recalls him saying. “But the only thing I’ll say is that the day I find you, I swear, I will kill you.” Strangers provided food and clothing along the journey north, but there were still cold, sleepless nights and periods of hunger. She was not the first member of her family to leave Honduras. Her sister was already living in Florida, and her previous partner and their four-year-old daughter were also in the state.

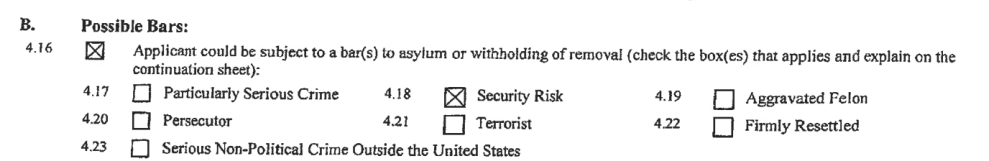

Weeks after the separation, Schommer received the paperwork from Alejandra’s credible fear interview. The asylum officer had checked two key boxes. The first showed that Alejandra had established credible fear; the second indicated she might not be eligible for asylum because she posed a security risk. “The fact that that box was checked was really disturbing to me,” Schommer says.

There wasn’t anything in the asylum officer’s summary of the credible fear interview that should have caused that box to be checked, Schommer says, and there was no mention of separating Alejandra from her child. The security risk box indicates that a person could “pose a danger to the security of the United States” and does not mean someone is a threat to her child or other detained migrants. “It’s still, to me, kind of inexplicable,” she says. “And then it just made me frankly more angry that someone checking a box, when legally the box should not be checked, resulted in this mom being separated from a two-year-old.”

An asylum officer marked “security risk” on Alejandra’s form.

If information disclosed in credible fear interviews is being used to force family separations, Govindaiah says that raises a number of concerns. Credible fear interviews are not recorded or officially transcribed. Instead, asylum officers take notes and summarize the interview in a written report, which can make it harder for migrants to challenge asylum officers’ characterizations and decisions. An additional complication is that asylum officers work for USCIS, while separation decisions at family detention centers are handled by ICE. Following the asylum interviews, Govindaiah says, “ICE somehow makes a determination—based on what, who knows?—that this mother can no longer care or provide custody for her child.” He adds, “I imagine that the asylum office is not aware that checking that box might mean separation.”

Govindaiah is particularly concerned about separations based on a “vague notion” of gang ties. “In any other body of law, in order to justify the separation,” he says, “I think the government would have to prove that their are actually gang ties and [that] the gang ties prevent this parent from caring or providing custody for their child.”

Once Alejandra was separated from her daughter, Schommer concluded there was nothing that could be done to quickly overturn the decision. She believed asking ICE to reverse itself was so unlikely to succeed and not worth the time. About a month passed with Alejandra stuck in detention in Pearsall and her daughter in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services in Michigan. They were supposed to talk on the phone once a week, but Alejandra’s phone calls often went unanswered. When they did talk, Graciela would sometimes show off the English she was learning by counting to five or saying “I love you.”

In June, Graciela left government custody and moved in with Alejandra’s sister and brother-in-law, who had offered to sponsor the girl, in Florida. Alejandra hoped to see them soon: Since she’d passed her credible fear interview, she was eligible to be released from detention. If she got out on bond, she could join her daughter in Florida and effectively sidestep the separation decision.

Trump’s family separation policy ended the day Alejandra went in for her bond hearing in June. Schommer was ready to contest the government’s claim that she posed a security risk, but DHS’s legal team never even brought it up. Instead, DHS focused on an announcement Attorney General Jeff Sessions had made the week before, dramatically limiting gang violence and domestic violence as grounds for asylum. The government argued that the announcement made Alejandra less likely to gain asylum, and as a result she would be a flight risk. The judge acknowledged the potential impact of Sessions’ decision and set an unusually high bond of $9,000. But Alejandra was able to cover the cost with help from her family and a bond fund run by RAICES.

On July 3, nearly three months after being detained at the border, Alejandra was released from detention. She arrived in Florida on Independence Day, and her sister and Graciela were waiting to meeting her at the airport. After 10 weeks apart, Graciela now appeared afraid of her mother. “Come here, my love,” Alejandra said. But Graciela didn’t want to, and Alejandra began to cry. “You have to understand,” her sister explained. “She’s been with other people. For her, three months is an eternity to go without seeing you.”

By the time Alejandra and I first spoke two weeks later, Graciela had swung to the opposite extreme. “Now she doesn’t want to be apart from me, not for a little bit, not for an instant,” Alejandra says. “She always comes with me.” In Alejandra’s eyes, her daughter was not the same; she was “another human.” She cried when people talked loudly. And her new English vocabulary was alarming. “I don’t know who taught them to her where she was, but she almost only told me bad words,” Alejandra says—words like “fuck” and “shit.”

Govindaiah says other mothers separated at family detention centers have followed the same indirect route to reunification that Alejandra took. In some cases, ICE’s legal team has accepted relatively low bonds for separated mothers and stated that there is nothing negative in the mother’s file. “That completely undercuts the decision by ICE to separate,” he says.

Alejandra’s case has much in common with that of one of the mothers RAICES’s Russell has assisted, who is identified as M.G.U. in a lawsuit challenging the family separation policy. In May, while at the Dilley family detention center in Texas after fleeing Guatemala, she was told the same story as Alejandra: The good news was that she passed her credible fear interview; the bad news was that she was being separated from her three children.

Gerardo Aguilar, a supervisory deportation and detention officer for ICE, said in a court declaration that he decided to separate M.G.U. from her children because she had been convicted of “Making False and Misleading Representations.” The conviction was for a nearly two-decade-old, nonviolent offense, but that didn’t matter. Nearly two months later, ICE reunited M.G.U. with her children, in accordance with the court order that required the Trump administration to reunite separated families. The court order allows DHS to keep families separated if it believes parents pose a threat to their children. ICE’s decision to reunite M.G.U’s family despite that carveout further undermines the rationale for separating them in the first place and shows how arbitrary the decisions can be.

There is no guarantee that separated parents receive the legal aid that helped Alejandra and M.G.U. Migrants have no right to counsel in immigration court proceedings. It’s also hard to find separated parents, Govindaiah says. “Many times, it’s the mother who calls us,” he says. “Like a week, or a day, or several weeks later, saying ‘Hey, I’m actually at this other detention center. Can you still help me? And what is happening with my kid? Because I know nothing.’” Katy Murdza, the advocacy coordinator at the Dilley Pro Bono Project, says in an email that her organization is “very worried” that families have been separated at Dilley without the organization’s knowledge. “We see such a high volume of clients that we often hear about these separations by chance,” she explains.

Alejandra did not respond when I texted in her early August to see how she was doing. Three weeks later, she got in touch. She had no news about a court date, but she wanted to find Graciela a psychologist. She was traumatized, Alejandra said, and was acting as she never had before.

When we spoke a few days later, Graciela wasn’t eating much, and a doctor had recently told Alejandra she was underweight. Graciela was happy when they went to the pool or the park. Still, she cried when people approached her, and she woke up crying three or four times a night. She hardly ever wanted to eat. She barely spoke.

Alejandra was in contact with other separated mothers she met in detention, none of whom had yet gained asylum. Alejandra knew her case would be tough, too. But she was not afraid. “In this country, everything will change because I have faith,” she said. She wanted to go home and see her parents, but knew she couldn’t. “I want to fight my case here,” she said. “For my sake and for my daughter’s sake.”

Last month, a social worker came to Alejandra and her sister’s home to make sure everything was in order before returning custody of Graciela to her mother. After they signed the papers, the social worker asked Alejandra how it felt to have custody again. Alejandra began to cry. “I told her that I felt very happy because it’s tough to have your daughter, but not to have her papers,” she says. “To know that someone else has to be responsible for her.”

Graciela was doing better when I spoke to Alejandra last month. Instead of waking up three or four times a night, she was waking up once to drink milk. She was crying only when she was apart from her mother.

But for Alejandra, there was still no avoiding how hard the separation had been. “These are things I wish on no one,” she says, “because they are things that no one can explain.”