Carbon Tax Center

I’ve gotten a few emails asking why I’m not thrilled with the “tax-and-dividend” proposal that’s part of Andrew Yang’s climate change plan. Tax and dividend is a hot topic these days, so my skepticism probably deserves to be teased out a bit. Here it is.

Tax-and-dividend starts out with a carbon tax. In Yang’s case, it starts at $40/ton and gradually increases to $100/ton. To give you an idea of what this means in real life, it’s equivalent to a gasoline tax of about 36 cents per gallon, rising over time to 88 cents per gallon. There are three obvious things to say about a carbon tax at this level:

- It’s pretty small. An increase of 10 percent in the price of gasoline would have a tiny effect. Even 88 cents wouldn’t do much. Nor is this just a guess: we know a fair amount about the price-elasticity of gasoline, and we know that it’s quite modest.

- It’s a regressive tax. Obviously a flat gasoline tax hurts the poor more than the rich.

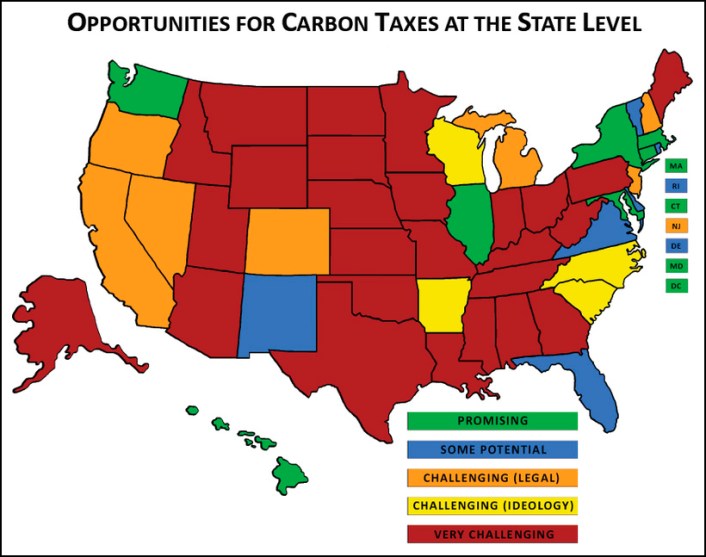

- It affects different regions differently since the effect on electricity prices depends on how carbon-heavy your electricity is currently. In California, for example, electricity prices would likely increase by only about 50 percent because California already relies heavily on renewable sources. In the South, by contrast, the price of electricity would triple because of the region’s heavy reliance on coal. The map at the top of this post, from the Carbon Tax Center, gives you an idea of which states would probably be hardest hit by a carbon tax.

This is where I start: a smallish carbon tax would generate a lot of opposition—from anti-taxers, from advocates for the poor, from states that are hardest hit—but wouldn’t produce a big effect. It’s not clear that it’s worth it.

So maybe we make it bigger? How about $400 per ton? That would add three or four dollars to the price of gasoline and would increase the price of electricity by 10x or more. That would have an effect. Needless to say, it would also generate massive opposition. This is probably not the hill we want to die on, because die we would.

But wait. How about a middle approach? Yang proposes that we impose a carbon tax but then give back some of the money. He’s vague on how this would be done, but presumably the money would be doled out mostly to low-income families. Maybe some would also be earmarked for regions that pay an especially high price.

But now you have a different problem. The whole point of a carbon tax is to make energy more expensive so that people will use less of it. But if you just give the money back, it means people can use their dividend to partially offset that higher cost. They can go on using the same amount of energy as always with minimal pain.

Of course, there would still be middle-class and high-income people who would have to pay higher prices and wouldn’t benefit from the dividend. That’s no big deal for those with high incomes, who can absorb the modest price increase without even feeling it. So that leaves the middle class: too rich to qualify for dividends but still poor enough to feel the pinch of the carbon tax.

Is that what we want? A carbon tax that, in practice, is shouldered almost exclusively by the middle class? It’s not what I want. Not that it matters anyway: put some meat on a plan like this and Republicans will instantly start producing ads showing precisely how much it will cost real American families struggling over their real American bills at a real American kitchen table. It’s not as if you can wave your hands and hope that nobody notices. Even a modest carbon tax would be a very big political lift.

I should be clear here: this is a change in my thinking. Ten years ago I wrote a piece for Mother Jones extolling the virtues of cap-and-trade, which is basically just a variant of a carbon tax. Everything I said then is true: carbon taxes are economically efficient; they’re fairly easy to implement; they produce funding for green initiatives; and they spur technology innovation. But those were more optimistic times, a brief period when it seemed like people were finally taking climate change more seriously and Barack Obama’s charm might be able to put a deal over the finish line. Needless to say, that’s not what happened.

What happened instead was that hard-hit states in the South and the Midwest rebelled. Obama himself had other, higher priorities. The bill got larded up with exceptions and subsidies for every interest group you can think of. And then it failed anyway.

What I failed to pay enough attention to was basic politics. Politically, the key to any climate change policy is simple: it’s all about pain vs. effectiveness. You definitely want to support policies that are low-pain but highly effective. You might want to support policies that are high-pain but also highly effective. But high-pain combined with only modest effectiveness? That’s a killer. The public just won’t support it, no matter how convinced the rest of us are about its righteousness. You should run away.

So that’s where I am with carbon taxes. From a white-paper point of view, they’re great, but from a real-world point of view they just don’t cut it. Progressives won’t support a regressive tax so they fiddle with it. But in fiddling with it they make it less effective. Then states that would be heavily hit get in on the action and demand some concessions of their own. The Senate being what it is, there’s no choice but to cave in. Special interests chime in and get some concessions. Negotiations bring the original tax rate down a few notches. By the time you’re done there’s not much left. You’ve got a smallish incentive and a large group of middle-class voters who are pissed off. It’s quite possible that when it’s all said and done, you could end up with a carbon tax that accomplishes little and produces less net support for climate change action than you had going in.

Now, my analysis could be wrong. I’m wide open to opposing arguments. But I fundamentally think that if progressives truly want to fight climate change, we need to focus on initiatives that produce low pain but have the potential to be highly effective. That’s not easy. But nobody ever promised that it would be easy.