An Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainee listens to a fellow detainee, a Pentacostal preacher, in a chapel at a for-profit jail in Louisiana in September.Gerald Herbert/AP

On Wednesday, as experts warned that hospitals could soon be overwhelmed, a Cuban doctor was stuck inside a for-profit detention center. Like many people in immigration jails, she was afraid of what would happen if the new coronavirus entered the facility. For the past three weeks, she and nearly 50 women have been quarantined because of recurring bouts of the flu at GEO Group’s Basile, Louisiana, detention center.

On Wednesday night, Immigration and Customs Enforcement said it would scale back arrests in response to the pandemic. But the agency said nothing about releasing people who are already in ICE custody, one of experts’ top recommendations for preventing the virus from spreading within immigration jails and other detention facilities. In response to questions about whether ICE plans to let anyone out—particularly those who are vulnerable to the effects of the virus—an agency official said, “There has been no announcement related to releasing individuals that are currently detained.”

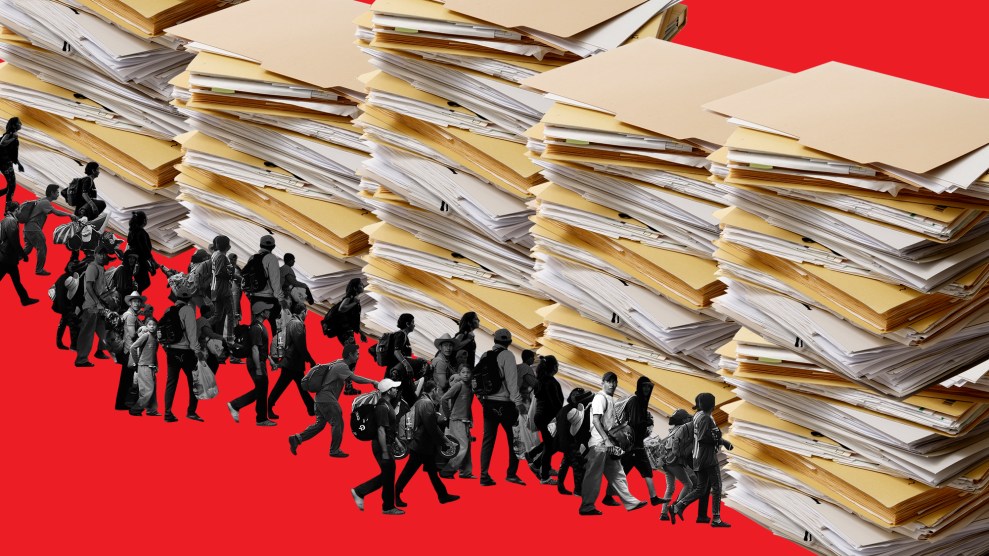

Data released by ICE on Wednesday night shows that the agency is keeping detention numbers high. As of Saturday, ICE had 37,311 people in custody, down only slightly from 37,888 the week before. More than 60 percent of those detainees—22,936 people—do not have criminal convictions. Among the 38 percent of detainees who do have criminal convictions, many have only committed minor offenses like crossing the border without authorization.

Nearly 6,000 of the people in ICE’s custody have established a significant possibility of being persecuted or tortured in their home countries. Instead of letting them live with relatives or others who are willing to house them, ICE is holding them in places that are often notorious for unsanitary conditions and inadequate medical attention.

As Eunice Cho, a senior staff attorney and detention expert at the American Civil Liberties Union, told me last week, ICE has broad authority to release people in its custody. “The question,” she said, “is whether the government will actually exercise this and mitigate what continues to be a very foreseeable disaster.” So far, attorneys in Louisiana say ICE appears set on keeping people in detention.

In a letter published on Thursday, Carlos Franco-Paredes, a professor in the University of Colorado School of Medicine’s infectious diseases division, painted a grim picture of how the coronavirus could affect people in detention:

For an immigration detention center that holds 1500 detainees, we can estimate that 500-650 may acquire the infection. Of these, 100 to 150 individuals may develop severe disease potentially requiring admission to an intensive care unit. Of these, 10-15 individuals may die from respiratory failure.

The new detention data, which ICE updates on its website each week, also shows that the agency did not significantly reduce arrests between the first and second weeks of March. It’s unclear how much will change after Wednesday’s announcement that ICE “will focus enforcement on public safety risks and individuals subject to mandatory detention based on criminal grounds.” Ken Cuccinelli, the Department of Homeland Security’s acting deputy director, posted tweets on Thursday that downplayed the significance of the shift.

The data also shows that ICE detainees continue to spend far longer in detention than they once did. People without criminal records who are stopped at the border now end up detained for an average of two months. That’s up from as few as 17 days last spring, when a dramatic increase in border crossings limited the agency’s ability to subject people to indefinite mandatory detention.

The Cuban doctor, who requested anonymity because she fears retaliation, has been detained for eight months. Despite that, she’s still awaiting an initial decision in her asylum case. ICE has denied her request to be released on parole multiple times. ICE considers her a flight risk because she lacks immediate family in the United States, she said.

Before coming to the US, she spent nine years in Cuba studying to become a doctor of general medicine and hopes to keep doing that work in the United States. “I love my career,” she said. “I want to keep being a doctor for my whole life.”

For now, she and other women who’ve called me from Basile say that even basic hygiene can be a luxury, explaining that they don’t have access to hand sanitizer and disinfectant wipes. The doctor said they’re provided 12 ounces of liquid soap one week, then four the next. She said it isn’t enough. They have to use the soap while shaving, showering, and, most important these days, washing their hands. If they run out, bars of soap at the commissary cost about $2. Most of the women can’t afford that, the doctor said. Thanks to the money her family sends, she could. (Christopher Ferreira, a GEO Group corporate relations manager, said soap and other hygiene products are free and readily available at the company’s ICE detention centers; he didn’t reply when asked if the company sells those products in its commissaries.)

From inside detention, the women have been watching the news on Telemundo and Univision. They see President Trump declare the pandemic a national emergency, and listen to calls for social distancing while stuck in a large room with about 45 other people. Relatives and volunteers cannot console them in person: ICE has banned social visits for the time being.

The husband of one of the women quarantined at Basile—Elio Almaguer-Guerra—called me with concerns about his wife, Katherine Ramírez-Escalona. He is an agricultural engineer, and she was studying medicine before the two of them left Cuba together last year. They arrived at the US-Mexico border in May, where they had to wait about six months to be allowed to request asylum in the United States. From there, he was sent to New Mexico, while she went to Louisiana. In January, Almaguer-Guerra was released on parole to live with his wife’s cousin in Miami.

But ICE’s New Orleans office, known for being one of the harshest in the nation, has refused to let Ramírez-Escalona join her husband and live with her cousin. Almaguer-Guerra feels hopeless and doesn’t know how much more either of them can bare. He contemplates dramatic measures—a protest in front of the White House or a hunger strike mounted on her behalf.

When the doctor and I spoke again on Thursday, she passed the phone to Leidy Vazquez-Moreno, a Cuban accountant who’s been practicing English while working in the detention center’s library. “We are very scared about this situation,” she said in English. “I know the situation of the country, and I know we are only immigrants, but we are humans asking [for] help.”

The US government, Vazquez-Moreno continued, didn’t have to be paying to keep them in detention when they had family members who’ve offered to take care of them. The money being used to detain them, she noted, would be better spent responding to the pandemic.