Evan Vucci/AP

Joe Biden wouldn’t back the Green New Deal. Throughout the Democratic primary, he acknowledged the urgency of the climate crisis, but maintained any solution should be “rational and affordable.” Instead of committing to the vision Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) had put forth, Biden proposed his own plan to create 10 million green new jobs.

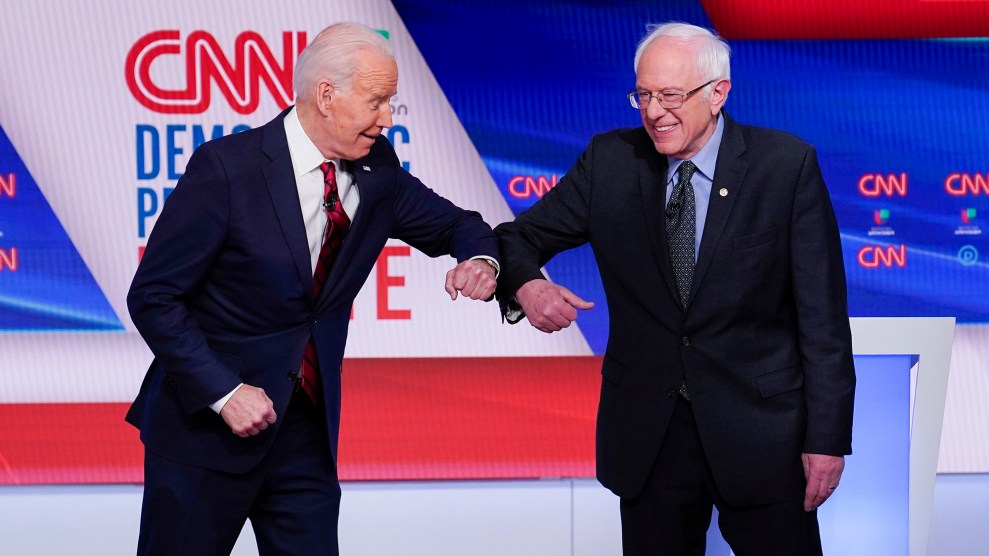

Ocasio-Cortez wasn’t ready to give up. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) had appointed the New York congresswoman to serve as a co-chair of the climate “Biden-Sanders task force,” one of six panels of allies from the Democrats’ more moderate presidential nominee and the primary’s leftist runner up tasked with collaborating policy recommendations amenable to both camps. Ocasio-Cortez privately consulted her co-chair, former Secretary of State John Kerry, about the possibility of a “climate corps,” an apprenticeship program for young people to enter the conservation and clean energy workforces that both she and Varshini Prakash, a founder of the youth-led Sunrise Movement and fellow Sanders appointee, had strongly advocated for. Kerry agreed with its merits, and Ocasio-Cortez says he told her he got the former vice president to agree to the idea too.

The idea is one of many progressive darlings memorialized in the recommendations from the Biden-Sanders task force, which the Biden campaign published on Wednesday afternoon. The input from the six groups—dedicated to criminal justice reform, the economy, education, health care, and immigration—are intended to inform both the platforms of Biden and the Democratic National Committee. The intention behind the groups was to give Sanders’ allies a say in policy and personnel decisions while mollifying the Sanders supporters who had bitterly and vocally rejected Biden throughout the party. In addition to the “climate corps,” the task forces’ recommendations include a 2050 deadline to achieve net-zero carbon emissions—more aggressive than what Biden has previously proposed—and post office banking for the millions of Americans without bank accounts.

To those in the Sanders camp, the recommendations are promising, albeit imperfect. The asks left on the cutting room floor were among their most precious: Medicare-for-All and a federal jobs guarantee, in which the government promises to hire unemployed workers in the event they can’t get other jobs.

Still, Faiz Shakir, who managed Sanders’ 2020 campaign and oversaw the task forces, told me he thought “Biden is moving in a progressive direction,” and walked away encouraged about the process. “There was understanding with both campaigns’ part, we need to have trust-building among the various loyalties within our party; this kind of a setting is a part of that.”

Biden didn’t do much with policy during the Democratic primary, defining his quest for the White House on a return to decency. The policy-obsessed Sanders, meanwhile, premised his candidacy on bold plans to cancel student debt, establish a single-payer health care system, and provide free public college to everyone. Since the pandemic took hold in March, progressives have argued that its ensuing health and economic crises made a case for Sanders’ government-heavy approach, and this particularly bore out in the health care task force, where Sanders representatives, who supported Medicare-for-All, were at odds with the Biden flank, who supported a public option.

The health care recommendations include guaranteed access to free- or low-cost health care plans throughout the pandemic and automatic enrollment in public health insurance for low-income Americans already receiving other safety-net benefits. “We’d had a very clear debate during the primary about where we stood,” says Abdul El-Sayed, a public health expert and former Michigan gubernatorial candidate who represented Sanders on the health care task force. “But there was a recognition that walking into the post-COVID world with a pre-COVID plan wasn’t going to cut it.”

Other topics, however, showed the limitations of the Bernie wing’s sway. This was particularly true on the economics task force, where the Sanders allies, skeptical of the need to offset major government programs with allocated funding, butted heads with the Biden camp, which argued for the need to limit the federal deficit. “The biggest constraint was, ‘How are we going to pay for it?’” says Darrick Hamilton, an economist who advised Sanders’ campaign and served on the task force. “When you ask that and say you aren’t interested in a wealth tax, it becomes a nonstarter for big, bold initiatives.”

These differences came to a head over the battle for a federal jobs guarantee. While the Biden camp conceded that such a measure could be enacted during a pandemic, they wouldn’t commit to something like that permanently, with Biden’s team raising concerns about the deficit. In the end, the recommendations point to the need for “jobs programs like those effectively used during the New Deal,” but not to such a program for the long-term. For several participants in the economic task force, that had been emblematic of the outcome: The tone and rhetoric of the recommendations were bolder than the actual policies.

But Hamilton says he views the at-times tense disagreements as a sign that the Biden campaign engaged in good faith and will actually adopt some of the policies the teams suggested. “We pushed Ben [Harris], and he took us seriously,” Hamilton says of his interactions with Biden’s economics adviser. “They didn’t want this to be a failed endeavor.'” Harris, who had never previously met Hamilton or the other Sanders economics appointees, economist Stephanie Kelton and labor leader Sarah Nelson, said he really enjoyed getting to know them. “Honestly, if you’re going to have these big ideological disagreements, it really helps to enjoy and respect the people you’re disagreeing with,” Harris said.

Progressives had raised eyebrows about the value of the task forces when they had been announced alongside the suspension of Sanders’ campaign in April. It had been the ask Sanders made of the Biden campaign as he conceded, and to many, it didn’t make sense. Sanders, after all, had a say in the party platform after his loss to Hillary Clinton in 2016—without an intermediary group of negotiators whose recommendations aren’t even guaranteed to make their way to Biden’s campaign promises.

Shakir says that the Biden side engaged seriously enough with the policy questions that he’s hopeful the proposals will their way into the campaign. “We asked, ‘How do you write this policy in a way that you would adopt it?’” he says. “These are the things they feel comfortable with, and they’re written in a language that shows they’re serious.”

But that commitment may not wholly be there. When I asked Harris if Biden himself had signed off on the economic policy recommendations Harris dodged and wouldn’t confirm anything, noting only that he and Jared Bernstein, another economist advising Biden, offered ideas they had discussed with Biden.

So the question remains: How important is this going to be? The 100 pages bear close similarity to a party platform document, something that’s composed thoughtfully, then summarily dismissed once a candidate enters the White House. “Obviously it’s a values document,” says Hamilton, “but it’s one he may just ignore.”

This story has been updated.