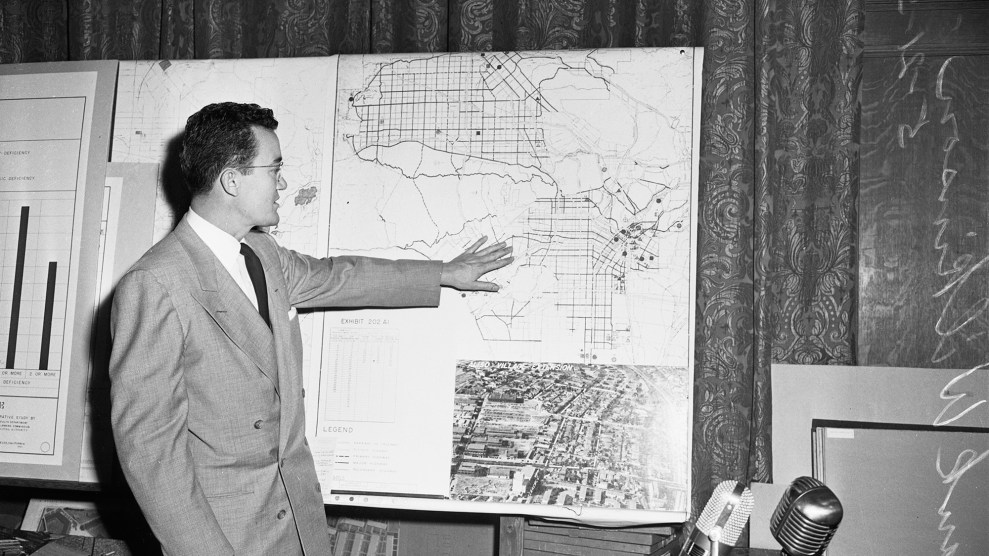

Frank Wilkinson at a 1952 housing hearing.USC/Corbis/Getty

This article is adapted from Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between (published this year by PublicAffairs).

The evening of March 4, 1964, Frank Wilkinson drove to a private home in Los Angeles to address a local meeting of the ACLU. This was the kind of thing Frank did all the time. He was a full-time, professional activist. Los Angeles was his home, but he gave speeches like this all around the country in big halls and on campuses and even in living rooms. Frank would talk to anybody who would listen. He would talk and talk and talk. His cause was free speech—specifically the abolition of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

It was a cause Frank believed in so deeply that he had even gone to federal prison a couple years earlier in an effort to prove that HUAC, by its very nature, violated the First Amendment. Frank had taken his case all the way to the Supreme Court—and he had lost. But losing made him a martyr and he was built for martyrdom. He walked out of prison and back into the life of activism he had left behind.

That particular night in 1964, the people Frank was to speak to were friends. The house belonged to an attorney named Allen Neiman—vice president of the ACLU’s Southern California chapter. Frank was not aware when he arrived at the Neiman residence that there were two men sitting in a parked car out in front of the house watching the ACLU members file in.

Nor was Frank aware of the fact that these men were federal agents.

And Frank was certainly not aware that that very day, the Los Angeles office of the FBI had reported to J. Edgar Hoover himself that the bureau had been “contacted by an undisclosed source to assist in an assassination attempt on Frank Wilkinson…March four… at 8 p.m. while Wilkinson addresses a meeting of the American Civil Liberties Union.”

Frank had a way of steeling himself up for speeches. He would dress as if arming himself for battle, his shirt and tie a part of the image he wanted to project: one of purpose and effectiveness. Normally Frank was a silly, social man, but before speeches he would become serious and introspective. That night he likely would have driven over to the Neiman household in silence, going over the speech in his head as he descended into the San Fernando Valley, parked on the quiet residential street, walked obliviously past the two agents, and knocked on the door.

By that point, Frank’s life had been destroyed already. It had happened a dozen years earlier. We know the date, in fact: August 29, 1952. Frank Wilkinson began that day a leading light in Los Angeles’ housing authority, a man on the verge of the greatest triumph of his career: the construction of 10,000 new units of public housing in Los Angeles, the crown jewel of which was to be called Elysian Park Heights, located in the hills that currently cradle Dodger Stadium. He would end the day a pariah, the target of an expensive, elaborate, and ruthless campaign of red-baiting that would also bring down his dream of public housing in Los Angeles.

At the time, Frank was 39 years old, a father of three, and it had already been a long journey. Frank’s father had been a prominent Methodist physician and anti-vice crusader in Beverly Hills. Frank grew up among church pews in a house where card-playing, dancing, and especially alcohol were forbidden.

But after college Frank shed his family’s conservative politics and religiosity to become a progressive activist and hard-charging advocate for urban renewal and public housing. Now he was finally his own man. His favorite word was “effective.” He liked to draw out the pronunciation: eeee-feck-tive. Everything in his life was geared toward effectiveness. Everything in his life was geared toward the cause.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Frank was the engine driving Elysian Park Heights, an ambitious housing project that would have towered over the downtown Los Angeles skyline; a project that he believed would change the face of the city forever. His was a utopian vision. Frank saw public housing as the key to racial harmony, to eradicating poverty. He was a true believer.

This was an era in which the future of development in Los Angeles was being hashed out in newspaper columns and city hall backrooms every single day. The region was in the midst of what seemed like a never-ending population boom that left its leaders constantly looking for— and fighting over—answers. The fight was not whether LA needed more housing, but whether the bulk of that new housing would should publicly constructed or privately developed.

That August morning, Frank took the stand wearing a tan suit and a broad tie. The wire from his hearing aid dangled down from his ear. He was ready to talk about eminent domain. But immediately after being sworn in, he was greeted with the question that would change his life forever: An attorney looked over a mysterious sheath of papers and abruptly asked Frank to please list all of the organizations, political or otherwise, that he had belonged to since his freshman year at UCLA.

The subtext of this question was clear to Frank and to everybody in the courthouse. In Los Angeles, opponents of public housing had spent years trying to tie the projects to Communism. The leading group opposing public housing was literally called CASH: Citizens Against Socialist Housing. Now Frank was being asked the question. The courtroom was silent.

Frank stalled. He listed his many innocent affiliations and associations. The attorney pressed him. Frank waited for an objection from his attorney. His personal politics were so far afield from the hearing or the subject of eminent domain—surely his attorney would step in. But that never happened.

Ultimately, Frank refused to answer the question. But it didn’t matter. By the end of the day, his life was ruined. He was fired. He was dragged across the front page of every newspaper in town. He was dragged before committees, including California’s local answer to HUAC. His wife, Jean, lost her job as a public schoolteacher. His sons were nearly booted out of their YMCA summer camp because nobody wanted Frank and Jean seen around the facility.

The blacklisting crushed Frank—and it also had an instant political impact. Frank and the housing authority had spent years working to clear out three communities that were nestled into the hills where Elysian Park Heights was to be built. Those communities—Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop—were largely Mexican and Mexican American. In order to justify using the site for public housing, Frank and his allies had argued relentlessly that they were in fact slums: unsafe and unsuitable for decent living. This argument did not sit well with the communities

Deputy sheriffs forcibly evict Aurora Vargas from her home in Chavez Ravine on May 8, 1959. Originally condemned as part of Frank Wilkinson’s public housing project, the house was torn down to make way for Dodger Stadium.

AP Photo/Don Brinn

themselves, which were prideful and somewhat isolated from the rest of Los Angeles, and had undertaken their own organized resistance to the public housing program.

Quite simply, the neighborhoods did not like having a bunch of outsiders from the government telling them how they were supposed to live. This was the very government that had restricted where they could buy property, that had failed to provide them adequate services, that had frequently whipped up anti-Mexican racism. Of course Frank Wilkinson was not equipped to see any of this: His progressivism was inherently paternalistic.

Even after he was blacklisted, Frank failed to see it. By then most of the homeowners in Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop had sold their properties to the housing authority. Only a few dozen families held out—buoyed by the hope that perhaps the demise of Frank Wilkinson might mean they would get to keep their homes. As the months passed and popular opinion continued to build against public housing, the odds of actually building Elysian Park Heights seemed to grow fainter and fainter.

But ultimately everybody knew that it would come down to the following year’s mayoral election. For now, the office still belonged to a staunch public housing supporter named Fletcher Bowron.

By the spring of 1953, Frank Wilkinson was barely going outside. He was wrecked, destroyed, broken down. He was a father of three, closing in on 40 years old, and he was living off the kindness of strangers. The world seemed to be working against him ever since that fateful day the previous August.

As a young boy in Beverly Hills, Frank had obsessed over the edges of his family’s lawn and the shine on his father’s car. It was a way to channel his angst; if everything looked right, then perhaps it was right. Now he was once again throwing himself into housework. He ironed his daughter Jo’s little dresses. He did the grocery shopping.

In the ensuing months, Frank retraced all his steps leading up to that hearing. He played out the events over and over. The mysterious sheath of paper. The long walk back to his office. The ensuing frantic search for an attorney. The day had ended with Frank in tears, parked in his brother’s driveway, so desolate that he had to be given a tranquilizer and carried into the house.

How could this have possibly happened? Frank had been in the party for a decade, but that membership was a closely guarded secret. He had even skipped out on the chance to run for Congress for fear of being exposed. He had literally burned his Communist Party membership card in the backyard.

Soon there would be a mayoral election in Los Angeles that would determine the fate of Elysian Park Heights and thousands more units of public housing. Frank’s career was finished. His life was a mess. But at least his vision of utopia wasn’t dead yet.

The issue came down to this: A few years earlier, the city had signed a deal with the Truman administration to build those 10,000 units of public housing. These units would be paid for with federal dollars. But in the ensuing years, support for housing on the city council had been ensnared by Red Scare conspiracies like the one that had ruined Frank Wilkinson and beaten back by private real estate developers.

It was an open question whether the city would honor its deal with the federal government. The answer would depend on who was elected mayor. The incumbent, Bowron, was a short, stout former judge who had already served for a dozen years. Bowron was a coalition builder. He had been swept into office after a recall. Bowron had plenty of flaws, but the one thing he wasn’t was corrupt. He was no zealot like Frank, but he supported the implementation of public housing—after all, a deal was a deal.

His opponent was a little-known congressman named Norris Poulson. Poulson was hand-selected by LA business interests, led by Norman Chandler, the powerful publisher of the Los Angeles Times. Poulson and his allies ran an aggressive, negative campaign, whipping up Red Scare fears and aggressively tying public housing to Communism. Frank was at the center of that campaign.

As part of this effort, an anti-housing councilmember invited a Michigan congressman named Clare Hoffman to Los Angeles. Hoffman was a proud fearmonger and conspiracy theorist—a fascist sympathizer who had tried to start a movement to get Franklin Roosevelt impeached for entering World War II after Pearl Harbor. He spoke at America First rallies and spread conspiracy theories alleging that fluoridated water, polio vaccines, and the mental health movement of the 1950s were elements of a grand Communist plot against America. He was also the chair of the House Special Subcommittee on Government Operations—technically meant to oversee governance, but in Hoffman’s hands a HUAC-style weapon.

Hoffman’s committee arrived in Los Angeles weeks before the election. Officially, they were there to investigate Communist infiltration of the housing authority. But everyone knew why they were really there: to make a big, messy spectacle of Bowron’s support for public housing. The move was so blatantly cheap that the Democrats on Hoffman’s own committee skipped out on the hearings. And even Poulson—the man most primed to benefit from the hearings—asked Hoffman to delay until after the election. But instead of rescheduling, Hoffman ginned up a televised frenzy. He delivered subpoenas right and left.

Amid all this, Frank Wilkinson’s phone rang. On the other end was Ignacio “Nacho” Lopez. Lopez—a Spanish-language newspaper publisher and civic activist—had worked closely with Frank in the housing authority. Now he had inside info: Hoffman had his sights on Frank. And Frank wanted no part of another red-baiting extravaganza.

“Soon after he called there was a knock on my door and I thought it was committee staffers coming to issue the subpoena,” Frank later said. “So I dashed out the back door, climbed over a fence to another street and met Nacho.”

López drove Frank to a Russian bath in the Boyle Heights neighborhood. There, of all places, they figured, nobody would come looking for him. But they didn’t think about the fact that the Russian bath was just down the street from the LAPD’s Hollenbeck Station and was a favorite hangout of officers there. Frank was known around Hollenbeck—he had managed the Ramona Gardens projects and lived in the nearby Estrada Courts projects. His picture had been all over the papers for almost a year.

As they walked through the bathhouse in only their towels, with subpoena bearers still scrambling around the city trying to find Frank, one of the cops turned and said, “Hey, there goes Wilkinson.” After that, he and López quickly dressed and fled. They drove out to Sherman Oaks, to the home of a couple Frank knew named Robert and Ann Richards. He was a screenwriter, and she had been an employee of the Writer’s Guild; both had been blacklisted from Hollywood after pleading the Fifth in front of HUAC.

While the hearings got under way, Frank stayed indoors and out of sight. “I drank homemade corn whiskey and watched the hearings on television,” he recalled. The hearings were a spectacle. Hoffman yelled and banged on tables. Frank watched with particular interest when LAPD Chief William Parker took the stand.

Frank and Parker had history. The year before, Parker had provided doctored crime stats to a real estate developer and anti-housing activist named Fritz Burns. Parker made it clear what side he was on.

As Frank watched, Parker produced a sheath of papers. This was, he quickly realized, the same document that the attorney at the eminent domain hearings had been referring to on that fateful day in court the previous August. This was the very document that had signaled Frank’s downfall.

On television, Frank watched as Parker testified that early in 1952 he had presented this very dossier to Bowron, as well as similar dossiers on nine other housing authority employees. Parker said he tried to convince Bowron that it would be politically expedient to remove Frank. But Bowron simply threw the dossier in the trash and said, “I trust that boy.”

Parker was then asked by the committee to read the dossier on Frank Wilkinson out loud, as long as he could do so in a way that did not compromise any ongoing police work. Parker said that he could read the entire file. After all, what do the politics of housing bureaucrats have to do with police investigations? “This information came to me through official channels,” Parker said.

Parker began to read. He had a way of sounding both casual and patronizing when he spoke about people he didn’t respect: “The report on Wilkinson, dated January 31, 1952, is entitled, ‘Wilkinson, Frank B.’ Wife: Jean Benson Wilkinson. 2019 Rodney Drive, Los Angeles, California.”

Coming out of Parker’s mouth, even the most basic aspects of Frank’s life came off as somehow ominous. He was born in Michigan. He was raised in Arizona. The family moved to Beverly Hills. At UCLA, he made a “peace action report” to a left-wing student organization. In Parker’s telling, everybody Frank interacted was a Communist. Every organization he dealt with was a Communist front—even his church. The organizations he addressed as a public speaker? Communists.

Frank wasn’t even a suspect—to Parker, he was a criminal. Parker referred to Frank not by his name, but as “subject.” Frank watched on the black and white TV from his hideout as Parker spelled out his entire life, down to the most inconsequential detail:

“On October 26, 1946, subject endorsed an organizational conference of the Congress of American Women (CP Front Organization) held at the Friday Morning Club.”

At this point, Parker was interrupted by the committee’s questioning attorney.

“Is ‘CP’ Communist Party?”

“Yes. It is abbreviated.”

And on Parker went—the veteran home buying group? Communists. The meeting at Pepperdine College? Not organized by Communists…merely infiltrated by Communists. Parker saved his best touch for last.

“Subject has been an active member of the Communist Party, Los Angeles County section, for many years,” he said.

Parker offered no evidence of any kind. Nor was he asked to offer any. He did not even accuse Frank of any crimes. But it didn’t matter. Frank had now been declared, on live television, by the chief of police, to be a Communist. In the days that followed, Chandler’s Times ran story after story tying Bowron to the Communist Frank Wilkinson and to the Communist housing project.

Later, Frank would learn that the official channel that Parker was referring to was the FBI, which had begun surveilling Frank a decade earlier. But as he watched Parker on television, he just knew that somebody had been watching him and that this somebody had passed on this “official report” to the anti-housing attorneys.

It dawned on Frank that he had been the victim of what was essentially a conspiracy. He had been spied on by law-enforcement officials who compiled a dossier on his private life. The dossier, which contained nothing illegal, was then passed to persons outside of the law enforcement community who used it as part of a campaign of character assassination that they hoped would advance their own business interests. They were able to do this because of a climate of fear that they and their allies stoked as owners of influential media outlets.

Now the dossier was once again being used as a prop by law enforcement and anti-housing politicians in what was essentially a phony hearing meant to strike fear into voters and advance a candidate who had been hand-selected by those same private interests. Frank felt he had won a small victory by avoiding the subpoena and the spectacle of the hearings. But he had not avoided it at all.

It was a mind-fuck. It was dizzying to think about. But it was real. On one hand, it was horrible. All of Frank’s work in housing had been taken from him, and he himself had become the means by which the very thing he loved would be destroyed. Norris Poulson won the election. Elysian Park Heights was scratched, and building new public housing in Los Angeles wouldn’t be politically viable for the rest of his life.

On the other hand, Frank Wilkinson was at the center of the biggest story in Los Angeles, a martyr to a cause he believed in. There was something to be said for this. He had been so eeee-feck-tive at his job that powerful men like Norman Chandler and William Parker felt the need to destroy him. His vision for a slum-free Los Angeles had crumbled, but at least this was a sign that he had been doing something right.

This was something to build on. One thing Frank did not know was that his friends in the Communist Party had a nickname for him: JC. Frank had a savior complex, and a martyr complex to match it. If he couldn’t build public housing, perhaps at least he could throw himself into the fight against the forces that destroyed it.

In their own way, the hearings helped lift Frank out of his funk. They helped give him purpose. In the years to come, Frank would go on to become a fierce advocate for First Amendment rights—in particular for the abolition of the House Un-American Activities Committee and the kind of politics that had destroyed him. This fight would take him around the country, and ultimately to federal prison when the Supreme Court rejected his challenge to the legality of HUAC. It would lead to a lifetime of fighting powerful, entrenched enemies, a lifetime of looking over his shoulder.

That night in March 1964, Frank drove over the hill and into the San Fernando Valley. He parked his car and walked into Neiman’s home, oblivious. The people inside were his friends and fellow travelers. It was a normal meeting. The kind Frank had attended a thousand times. At one point, somebody at the party noticed the two men out front. Neiman went outside and wrote down their license plate number. He called the police. By the time a patrol car arrived, the two men were gone. The meeting continued, there was no assassination, and everybody forgot about the strange car in front of the house. It was just one of those things.

Weird things kept happening to Frank Wilkinson, though.

In the spring of 1969, a team of armed burglars broke into the small Los Angeles office of Frank’s organization, the National Committee to Abolish HUAC (NCAH). The burglars smashed the doors with sledgehammers and tied up an administrative assistant, holding her at gunpoint while they tore through filing cabinets. Finally, they left with a single folder marked “CORRESPONDENCE.”

Nobody thought much of the robbery at the time. The NCAH suffered break-ins relatively frequently. After all, they had spent the better part of a decade organizing to end the House Un-American Activities Committee—this meant they had developed a lot of enemies both inside and outside government.

Then, a few years after the break-in at his office, Frank read a newspaper article that caused him to reconsider the burglary. The story was about the team of burglars who had broken into the office of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate Hotel, Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office in Los Angeles, and various other locations as part of what would become known as the Watergate scandal.

The burglars who had entered the NCAH office to steal that single folder had been speaking Spanish—just as the Cuban burglars implicated in the Watergate scandal had been. Wilkinson believed there might be a connection. He wrote to Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox.

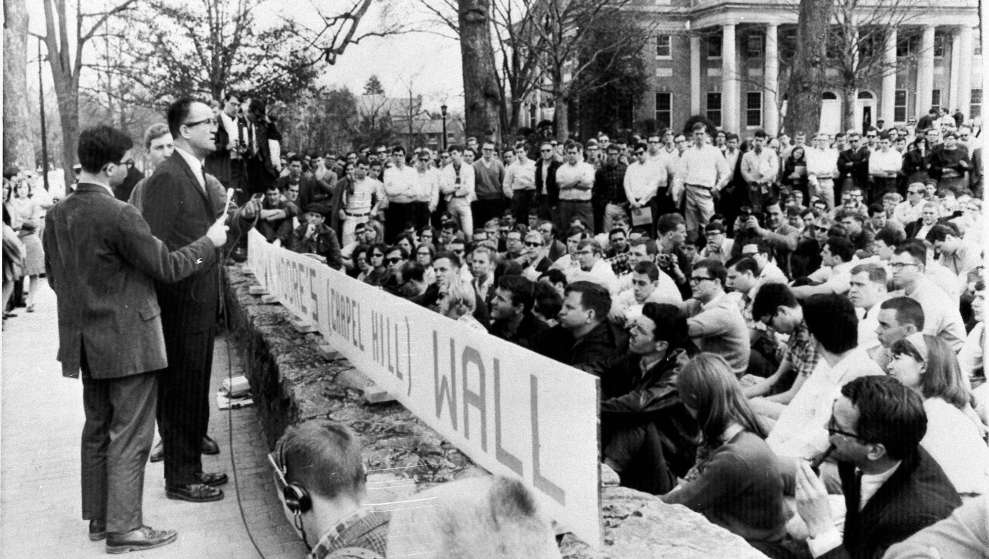

Frank Wilkinson speaks to North Carolina students in 1966.

AP Photo/Perry Aycock

Cox replied promptly and then spent a couple years investigating the Los Angeles break-in. But then, just before he was fired in the Saturday Night Massacre, Cox came to the conclusion that he could not prove any kind of connection between the Watergate scandal and the break-ins in Los Angeles. Instead, Cox suggested that Wilkinson speak with the FBI.

As Wilkinson later put it, a pair of FBI agents in matching suits soon appeared in his office. As a joke, a silly ice-breaker, Frank asked them if the FBI itself had by chance been responsible for the burglary. The agents stared back at him, dead serious, and asked, “What date?”

Frank was stunned. He gave the agents the date and then called a friend at the ACLU. The possibility that the FBI of all people had burglarized his office was outrageous. But then again was it? After all, this would not be the first time Frank had discovered that there were forces at play in his life that he could not see. In fact, his entire life had begun to feel like a mystery—a mystery about himself, about his work, and about his country.

With help from the ACLU, Frank decided to file a Freedom of Information Act request about the FBI surveillance of him. The simple request unspooled into a massive decade-long legal battle. By the 1980s, Frank learned that the FBI had been surveilling him since 1942—right at the start of his career in housing. They had continued to watch him for more than 30 years: before, during, and after his stint in prison. His FBI file ran to 132,000 pages. All of a sudden, everything made sense. Reading the files, it was like looking back on the inexplicable and mysterious events of his life with the benefit of a decoder ring.

They had spied on him constantly and worked to subvert him at every turn. All those resources. All that manpower, just for him. He learned that J. Edgar Hoover had taken a personal interest in his case; that every time he went somewhere to speak, the agency worked to infiltrate his life and undermine him, even going so far as to recruit members of the American Nazi Party as counterdemonstrators. It was all right there in the files. The dossier that William Parker read at that hearing suddenly had an explanation, too.

Also in the files was the assassination attempt. There was no mention of any intervention on the part of the FBI. There was no mention of anyone warning Frank away. Only a brief, shrugging note in the following day’s memo: “No attempt was made.”

Eric Nusbaum is the author of Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between. He also publishes the newsletter “Sports Stories.”