Former gubernatorial candidate and former state Rep. Stacey Abrams waves to the crowd as she crosses the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Sunday, March 1, 2020, in Selma, Ala. Butch Dill/AP

Progress toward a more just and equal society is not something that will just come and smack you in the face, at least not in the South. It takes time. It’s slow. It’s incremental. Yet, whenever the rest of the country catches onto a campaign down South, there’s inevitably just so much damn handwringing when the results don’t go progressives’ way. Soaring headlines that predict the year of “the new South,” or that the “new Southern strategy” will gain momentum, or that “the (new) South’s gonna rise,” or…insert misguided cliché here, quickly turn sour, (over)selling the disappointment by the same magnitude, Oh, look at that, the South is still pretty damn red. But what so many of these pieces lack is crucial context, specifically the myriad ways in which progressive policy has been stymied for more than a century in the South, especially where it concerns Black voters.

So this time, before you start shouting about those dumb rednecks (hello, I guess), educate yourselves.

Raquel Willis, a Black transgender activist from Georgia, said it best on Twitter: “Y’all better speak precisely when talking about southern states. The most powerful and innovative organizers have been trying to transform the region for generations. Don’t turn your backs on their hard work for a cute, quippy, self-righteous put down.”

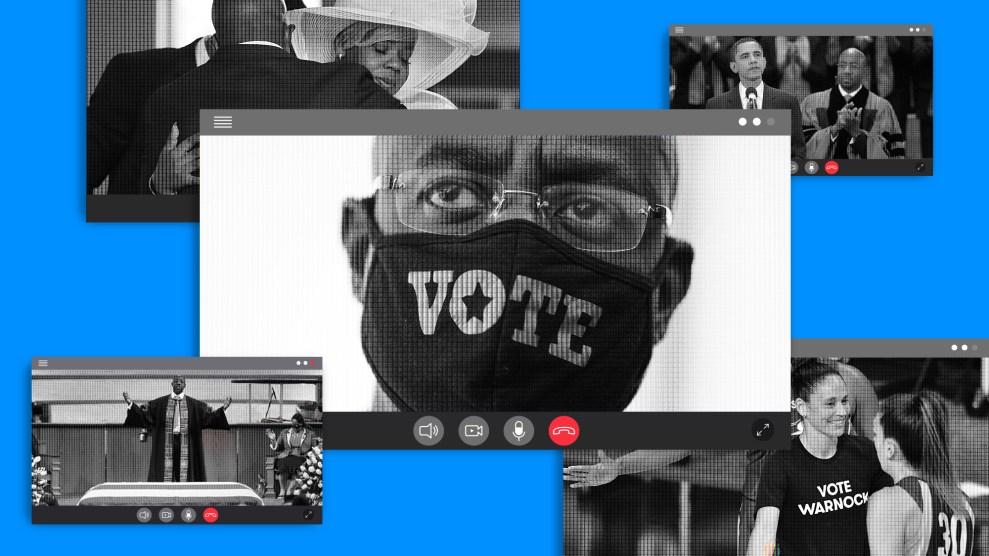

To be fair, on Friday when Joe Biden overtook Donald Trump’s vote share in Georgia, Democrats celebrated—and rightly so. The state is the closest it’s been to going for a Democratic presidential candidate in decades, and both Georgia’s races for US Senate seats will go to a January runoff. One Democrat candidate is Rev. Raphael Warnock, who would be the state’s first Black US Senator if elected.

But there was also a heap of impressive progress in the state and across the region that’s gotten way less attention. Georgia also elected its first queer state senator, Kim Jackson; Tennessee elected two of the first openly gay candidates to its state legislature; and Florida elected its first Black queer woman to the state House, Michele Rayner-Goolsby, and its first gay state senator, Shevrin Jones. Florida also raised the minimum wage in the state to $15 per hour. Mississippi not only voted to remove a Jim Crow-era provision from the state constitution that was meant to preserve white political power, but it also voted for a new state flag, officially moving on from the former Confederate design that was retired this summer. Alabama too voted to remove racist language from its state constitution, including old Jim Crow provisions banning interracial marriage and racially integrated schools. Virginia voters approved an amendment to form an independent, bipartisan redistricting committee in an effort to make its congressional districts less gerrymandered. And, as Adam Harris pointed out in the Atlantic, 2020 saw the largest number of Black candidates for political office in the South—the Deep South, in particular—since Reconstruction.

These changes came from grassroots activism that was made possible by a powerful spirit of organizing that has existed in the South since the Civil Rights Movement. And the Civil Rights Movement, of course, was born out of centuries of oppression and the dehumanization and enslavement of Black people. But the South’s history of white supremacy is old and so deeply entrenched in the identity of the place that carefully weeding it all out to allow more room for progress and equality takes time; I’ve written before about how that history lingers in the present day in ways that sometimes make it hard to recognize fully, even as it continues to cause harm. That is why we need to celebrate these small(er) victories when they happen—they are indicative of something much bigger.

It’s also important to note that the people who are fighting the hardest for equality in this country, but especially in the South, are also those who are the most disempowered by the infrastructure in place—think gerrymandering, felony disenfranchisement laws, voter ID laws, and voter roll purging, not to mention the vast economic inequalities that people of color face that reverberates through education, health care, and emotional wellbeing. That makes the organizing work being done in the South that is led by so many Black folks all the more incredible—not only should they not need to do this work in 2020 in the first place, but they’re doing it in the face of extreme adversity. I’m talking, of course, about women like Stacey Abrams, who has changed the voting demographics in Georgia through her voter registration efforts, and Nikema Williams, the state senator who was elected to the late Rep. John Lewis’ seat this week and is chair of Georgia’s Democratic Party. I’m thinking about the powerful history of the Black church, and the way Black churches and faith communities continue to lead the march toward justice in the South. There are the organizing efforts of Black Greek organizations; sororities like Delta Sigma Theta, Alpha Kappa Alpha (which counts Kamala Harris as a sister), Zeta Phi Beta, and Sigma Gamma Rho have played a significant role in voter registration, as have fraternities like Alpha Phi Alpha, which Warnock belongs to—his brothers have been at most of his campaign events. There are the Black mayors of the South—Steven Reed in Montgomery, Ala.; Keisha Lance Bottoms in Atlanta; Frank Scott Jr. in Little Rock, Arkansas; Randall Woodfin in Birmingham, Alabama; Vi Lyles in Charlotte, North Carolina; Chokwe Antar Lumumba in Jackson, Mississippi, to name a few.

Change comes slow, especially when so many of those fighting for it have been shoved to the bottom of America’s caste system. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening; it’s happening, and each change will continue to build on the one before it as history marches forward.