Democrats and Republicans alike have been eagerly grilling the CEOs of social media companies lately about their complicity in spreading disinformation. This is being done under the implied threat that if they don’t do something, Congress will do it for them.

I have a problem with this. Two problems, actually. First, everyone would be outraged if Congress hauled in the folks responsible for Rush Limbaugh and Fox News and Sinclair Radio and treated them the same way. So why is social media any different?

But let’s say that First Amendment concerns don’t sway you. Then this should: social media is most likely not a very important cog in the great right-wing disinformation machine anyway. A couple of years ago, Harvard scholars Yochai Benkler, Rob Faris and Hal Robert wrote a book about their research into disinformation, and here’s their conclusion:

Surveys make it clear that Fox News is by far the most influential outlet on the American right — more than five times as many Trump supporters reported using Fox News as their primary news outlet than those who named Facebook. And Trump support was highest among demographics whose social media use was lowest.

Our data repeatedly show Fox as the transmission vector of widespread conspiracy theories. The original Seth Rich conspiracy did not take off when initially propagated in July 2016 by fringe and pro-Russia sites, but only a year later, as Fox News revived it when James Comey was fired. The Clinton pedophilia libel that resulted in Pizzagate was started by a Fox online report, repeated across the Fox TV schedule, and provided the prime source of validation across the right-wing media ecosystem.

In 2017 Fox repeatedly attacked the national security establishment and law enforcement whenever the Trump-Russia investigation heated up. Each attack involved significant online activity, but the spikes in attention and transition moments are associated with Hannity, “Fox & Friends” and others like Tucker Carlson or Lou Dobbs.

More recently they took a look at the right-wing campaign to discredit mail-in voting:

Contrary to the focus of most contemporary work on disinformation, our findings suggest that this highly effective disinformation campaign, with potentially profound effects for both participation in and the legitimacy of the 2020 election, was an elite-driven, mass-media led process. Social media played only a secondary and supportive role.

Kevin Roose’s widely distributed list of top Facebook posts suggests what’s really going on:

Seven of these ten posts are from Fox News or Donald Trump. Facebook may help them get a little more reach than they otherwise would—though probably among true believers who hardly needed any convincing anyway—but it’s old-school media that generated all the attention in the first place. Facebook posters take their lead mainly from Fox and Trump and just follow along.

It also turns out that the “Facebook problem” hinges a lot on boring—but important!—classification issues. Richard Rogers of the University of Amsterdam notes that “fake news” encompasses vastly different things depending on how you define it:

Roomier definitions make the problem larger and result in findings such as the most well-known ‘fake news’ story of 2016. ‘Pope Francis Shocks World, Endorses Donald Trump for President’ began as satire and was later circulated on a hyperpartisan, fly-by-night site (Ending the Fed). It garnered higher engagement rates on Facebook than more serious articles in the mainstream news. When such stories are counted as ‘fake’, ‘junk’ or ‘problematic’, and the scale increases, industrial-style custodial action may be preferred such as mass contention moderation as well as crowd-sourced and automated flagging, followed by platform escalation procedures and outcomes such as suspending or deplatforming stories, videos and sources.

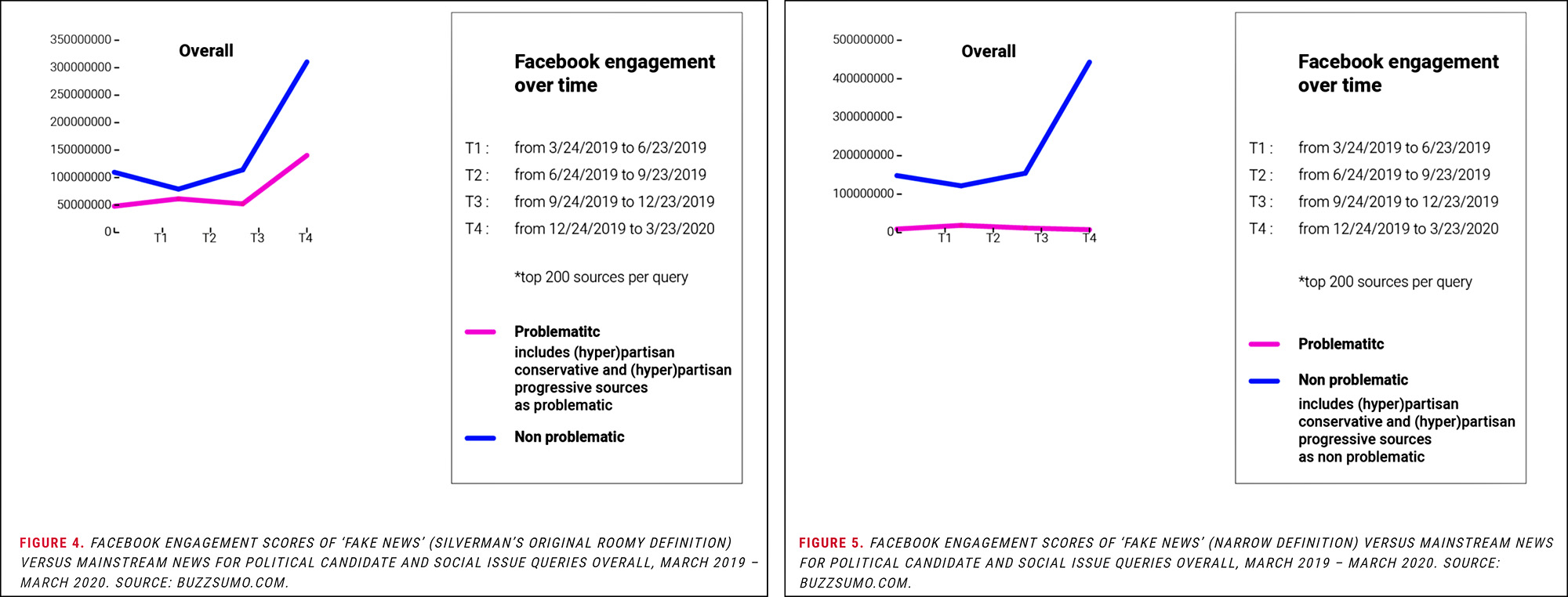

The chart below on the left shows engagement with fake news (pink line) using this “roomy” definition. But what if you restrict the definition of fake news to eliminate sites that are merely hyperpartisan or satirical, instead including only genuine imposter and conspiracy sites? Then you get the chart on the right:

Using this definition it turns out that engagement with fake news is tiny compared to engagement with real news. Of course, that real news includes hyperpartisan sites, and obviously those exist on a continuum that includes a lot of gray areas, but in general it turns out that the real crazytown stuff doesn’t get all that much attention.

None of this is proof positive of anything. But even if you assume the “real” definition of crackpot stuff is somewhere between the two above, it still suggests that we’re overestimating how much of it is getting a serious share of online eyeballs. There’s not much question that Facebook helps to amplify Fox News, and that’s obviously a problem for progressives. But does it justify regulating Facebook? Why not regulate the source instead?

Roughly speaking, I think the evidence points in one direction: When it comes to disinformation the real vectors are elite actors like Donald Trump, Fox News, talk radio, and so forth. They define the agenda, and Facebook just follows along. Relatedly, when elite players don’t play along, disinformation on Facebook gets very little traction.

To the extent that Facebook is yet another amplifier of the right-wing noise machine, it’s a problem. But it’s nowhere near the main problem. That remains just where it’s always been.