Illustration: Anita Kunz

HAROLD CASSIDY IS trying to break my heart. We’re sitting in his law office, minutes from the antiques haven of Red Bank, New Jersey, and a stone’s throw from the Navesink River. The room, furnished with a gleaming wooden table, green-and-brass banker’s lamps, and legal volumes lining the walls, could be the set for any movie about a small-town lawyer who lives by his passion for justice. Cassidy himself is a master of the dramatic narrative—his work has made him a collector of heartrending tales that, despite what must be countless retellings, he shares again with fresh intensity.

This one is about a girl he calls Donna Santa Marie, who discovered she was pregnant just before her 16th birthday. She and her boyfriend, both children of immigrants, were excited and wanted to get married. His parents gave their blessing; hers demanded that she have an abortion. Donna refused.

“Donna,” he says, drawing out each word for emphasis, “was very strong—exceptionally strong for a woman her age.” For two weeks, her parents let her go to school but otherwise would not let her out of her room. “And every day they wore on her; she had to have the abortion, she had to have the abortion. She just continued to refuse. They then made her a promise: They said, ‘If you get the abortion you can get married; in fact, we’ll hold a big church wedding.’ She still refused.”

Finally, Donna’s parents told her they would prosecute her boyfriend for statutory rape if she didn’t comply. So she went with them to the abortion clinic. When a clinic questionnaire asked, “What do you consider an abortion?” she wrote, “Murdering my baby.” To the question “Is anyone forcing you to have an abortion?” she wrote: “Yes, my parents.” Based on her answers, the doctor refused to do the procedure.

The parents were extremely angry, Cassidy explains, speeding up slightly; the next day, Donna’s father punched her in the abdomen, and a few days later he took her to another clinic. “Now, can you imagine,” he says, quiet outrage rising in his voice, “a 16-year-old girl putting up with this…” I’m expecting him to say “abuse,” but he continues, “…this great right, supposedly, this great right to choose?” Now he’s dripping with disgust. “And she goes into the waiting room and she’s waiting for her forms to fill out and they didn’t give her any, and they bring her back to a room and she’s sitting there waiting to talk to the doctor, and someone came in and anesthetized her.” Cassidy pauses.

“And they pulled the baby out.”

FOR ALMOST two decades, Harold Cassidy has quietly advanced the pro-life cause by giving legal shape to the stories of women who terminated their pregnancies and came to regret it. He has sued abortion providers for, among other things, not warning these women that they would experience the profound grief he’s convinced afflicts many who have ended a pregnancy. And while these ideas have become part of the vanguard of pro-life thinking—protect the woman, not just the unborn—few have heard of the man who helped bring them to prominence.

A tall 65-year-old who wears his size awkwardly, Cassidy has lived most of his life in this quiet corner of eastern New Jersey—”just one little person out in the horse country”—and kept his distance from mainstream pro-life groups. His wife has a desk at the front of the office, where she handles the phones; one of his sons, a young attorney named Derek, works alongside him. Cassidy rarely speaks to reporters and agreed to talk to me only reluctantly, after lengthy negotiations. “I’m not a messenger,” he insisted. “You’re trying to turn me into a messenger. I’m nothing but a lawyer.”

Still, talk he did, for more than a dozen hours, spread over multiple interviews that took place on weekdays, weekends, and holidays—and for which Cassidy, who has graying hair and a large mustache, invariably wore a dark suit and tie.

Cassidy, once a pro-choice liberal, sees the mother-child relationship as “almost sacred.” He returns again and again to certain themes: “the absolutely amazing, powerful, inherent instincts of women to love their children” and “their inability, when they lose their children, to put it completely behind them”—even when those “children” are embryos they chose to terminate. He also has come to the conclusion that “most abortions are the result of some level of coercion,” not just by partners or parents, but by a “culture that says, ‘Don’t bother us with your problem; we don’t want to help you in your time of need. Just dispose of the child.'”

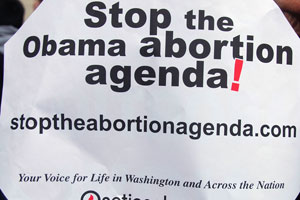

These beliefs have put him at the forefront of the pro-life movement’s biggest rebranding in recent memory, an effort that has gained tremendous traction among pro-life state legislators. (Ever since the November midterms, pro-life groups have been especially gleeful about their prospects at the state level; Operation Rescue leader Troy Newman told the New York Times, “I feel like a little boy on Christmas morning—which package do you open up first?”)

Of course, the notion that ending a pregnancy can be distressing is nothing new, and many pro-choicers have begun to acknowledge it—in a 2005 speech, Hillary Clinton famously called abortion “a sad, even tragic choice.” Some abortion clinics now refer patients to groups, like the California-based Exhale, that offer post-abortion counseling resources. But pro-lifers have taken the concerns much further. They have used the notion that women must be protected from abortion’s emotional impacts to justify a new round of laws (PDF) imposing mandatory ultrasounds and waiting periods, or forcing doctors to dole out discredited information about health risks. (See “Are You Sure You Want an Abortion?“) They’ve also championed state-mandated counseling scripts informing women that what they are doing amounts to taking a life—so that, the argument goes, a woman doesn’t later find herself overcome with grief over a decision she cannot undo.

In 2005, with Cassidy’s guidance, South Dakota passed one of the nation’s most restrictive counseling laws. Its language (PDF)—lifted directly from Cassidy’s legal writings—compels providers to tell women they are taking the life of a “whole, separate, unique, living human being.” The law, which Planned Parenthood is challenging (PDF) in federal court, has inspired imitators (PDF) in Missouri and North Dakota, with looser interpretations introduced in Indiana and Kansas.

These bills are not backed by mainstream scientific findings. In a 2008 review, the American Psychological Association found “no evidence sufficient to support the claim that an observed association between abortion history and mental health was caused by the abortion.” More recently, a team at Johns Hopkins University reviewed the relevant literature and concluded that the highest quality studies suggest “few, if any, differences between women who had abortions and their respective comparison groups,” while “studies with the most flawed methodology” found negative effects.

But the dry prose of studies can’t compete with vivid anecdotes of womanhood shattered and degraded. Cassidy is haunted by the modern-day pietá of the suffering post-abortive woman, and it’s that image he wants us all to see.

YOU DON’T understand Cassidy “until you understand him as a crusading 1960s liberal,” says Princeton University professor Robert P. George, a prominent conservative who has worked with Cassidy on anti-abortion efforts. Born in 1945, Cassidy grew up Catholic in rural Monmouth County, New Jersey. His parents were Democrats, his mother a cofounder of the local Democratic club. Theirs “was really the kind of view that Democrats stood up for the little guy, which was very appealing—still is appealing,” Cassidy told me. Growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, he learned to “believe in inclusiveness for everybody,” regardless of nationality, race, or gender. “When we go to high school and we learn that there was a time when women couldn’t vote, it’s a shocking thing,” he says. “And then you go to law school and you learn there was a time when women couldn’t own property and you say, ‘How could that possibly be?’ And as a male it’s embarrassing—because it was men who did this.”

Cassidy was drawn first to the law, then to engineering, and finally to the priesthood, spending a year in seminary before recognizing that it wasn’t meant to be. “It was me calling me,” he recalls, with characteristic humility. The law called him back, and he earned his degree in 1975 from

St. John’s University, studying under former New York governor Mario Cuomo. He and his wife Randee married in 1971 and had four children; the couple was politically involved, raising money for and supporting Democratic candidates throughout the 1980s.

From the start, Cassidy set out to defend the underdog. He was part of a team that worked to free Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a black boxer convicted of murder in 1967 and released nearly 20 years later. But his attention began shifting to issues of motherhood in 1981, when he received a call from a woman who was part of a network of birth mothers trying to reunite with children they’d given up for adoption years earlier. Other women followed. They invited him to their support groups and called him late at night. These were “really hard phone calls,” Cassidy says quietly. “People who know me as this abrasive guy are always surprised to learn how much these women really treasured talking to me in very dark moments.” He adds: “I guarantee you, no one in those days thought for one second about the birth mother. It was like she didn’t exist.”

It was around that time that he began to view biological motherhood as something in dire need of defense. “You can’t go through these experiences that I went through without having a very profound respect for the bond between mother and child,” Cassidy says. “And we’re talking about the bond during pregnancy and shortly after birth.”

In 1986, he agreed to represent Mary Beth Whitehead, a working-class surrogate fighting to keep the child she bore for an affluent couple, William and Betsy Stern, from her own egg and his sperm. The Baby M case made global headlines. Feminists were divided; some said women should be free to serve as surrogates and get paid for it if they so chose. Others, including psychologist and radical feminist Phyllis Chesler, sided with Whitehead. With protests and press conferences, they argued that paid surrogacy was a form of coercion, yet another way society encouraged poor women to sell their bodies. Chesler recalls being instantly taken with Cassidy. “He had a priestlike character,” she says. “He was self-sacrificing, he was devoted to the principles, he had sympathy—almost like the sympathy of the confessional—to both these mothers.”

The case went to the New Jersey Supreme Court, which gave custody to the father but also acted to outlaw paid surrogacy. When the ruling came down, Chesler arrived at a courthouse press conference with roses for Cassidy. But the opinion (PDF), which called paid surrogacy “potentially degrading to women,” was a victory for Cassidy in ways feminists did not anticipate: It put the moral value of motherhood in the spotlight and created an image of a grieving mother that Cassidy would evoke over the next two decades.

IN HINDSIGHT, it’s not hard to see how Cassidy’s adoration of motherhood would take him from adoption and surrogacy to abortion, but for years he didn’t view it that way. “This may sound very thoughtless,” Cassidy told me when I first met him four years ago, “but there was a point in time when I didn’t think at all about abortion or what abortion did to women.” He paused, and then confessed. “And so I was all for it.”

That began to change in 1990, when a couple came to him after their child was born with Down syndrome. The doctor had not done an amniocentesis, which might have diagnosed the condition, and they wanted to sue for “wrongful birth”—claiming they would have aborted had they known. Cassidy declined the case. “In this particular instance I was thinking, ‘What would it be like for me and for this little girl if I stood in the well of a courtroom and argued to a jury that they had to give lots of money to her mom and dad because they didn’t get a chance to kill her?'” he says. “That case forced me to ask the question, how did the law get this cruel?…It all led back to Roe v. Wade.”

He also started paying attention to the legal discrepancies between adoption and abortion. What impressed him, he told me, was that a woman thinking about giving away her baby can only terminate the mother-child relationship after the state helps ensure she’s making the right decision: In many states, she must wait until after birth to relinquish the child and must be offered counseling. “Those [maternal] rights are treated with the most profound respect,” Cassidy says, but “in the context of abortion, there is no respect…. My first question that I had for everybody—I’m talking about the courts, about people going into the courts claiming they represent the rights of women, about the pro-life community, the churches who like to talk about this issue—where is their discussion and defense of the mother, the real rights of the mother?”

He began reaching out, speaking with women about their abortion experiences and visiting crisis pregnancy centers, which were opening around the country to advise women to carry their pregnancies to term. “It was just me, wanting to be educated,” Cassidy says.

One of his first parries in the abortion wars came in an early-’90s case called Loce v. New Jersey, in which a man sued the state for failing to stop his girlfriend from having an abortion. Cassidy contributed a brief containing themes that would come to dominate his later work: “A mother’s relationship with her child during pregnancy is the most intimate, most unique, most important, and one most worthy of protection,” he wrote. “Preservation of the benefits, beauty, and joy of that relationship is one of the greatest interests a woman possesses in all of life.” Never mind that the would-be mother wanted no part of that relationship. “It was awkward,” Cassidy acknowledges. “It wasn’t the right case for it, but it was something I had passion for.”

The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled against the boyfriend. Around that time, however, a US Supreme Court decision in a case called Planned Parenthood v. Casey opened the door to widespread abortion regulations—invigorating the pro-life movement and its efforts to chip away at Roe.

By 1997, Donna Santa Marie—a not-so-subtle pseudonym for the 16-year-old who was allegedly coerced by her parents—came along. Cassidy and his allies launched a group called the National Foundation for Life to support the Santa Marie litigation, originally a class action involving three women who sought wrongful death payments, claiming that their abortions were not fully informed or voluntary. The case was the first step of the group’s Global Project—a strategy, according to promotional pamphlets Cassidy disseminated, “that will compel the Supreme Court to hear the case, and convince the Court that Roe can no longer be upheld in light of the new scientific facts and the legal conclusions which follow.” Cassidy assembled a team of scientists and doctors to establish these “new facts”: first, echoing a Loce companion case (PDF), that “the child is a completely separate, unique, and irreplaceable human being from the moment of conception,” and second, that abortion harms women by destroying their relationships with their unborn children. Cassidy also aimed to show that the kind of coercion Donna experienced was widespread, that an “entire generation” of women was “losing their children to doctors who literally have been given license to kill.”

The evidence, Cassidy’s circulars noted, would come from “hundreds of thousands of people who will enroll as ‘Friends of the Court.'” He teamed up with a fellow lawyer named Allan Parker—president of the conservative Texas-based Justice Foundation—to create Operation Outcry, a project that has solicited some 2,000 court-admissible declarations to date from women describing how abortion has destroyed their lives. The effort also received help from Norma McCorvey and Sandra Cano, lead plaintiffs in the two Supreme Court cases—Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton—that led to legalized abortion. The women filed briefs in Santa Marie arguing that legalizing abortion has harmed women, and urging that their own cases be overturned.

Despite Cassidy’s efforts, Santa Marie lost first in district court and again in 2002 before the Third US Circuit Court of Appeals. Because New Jersey law does not recognize a fetus as a person, the women could not collect wrongful-death damages. It seemed there were limits on how far Cassidy could advance his agenda in court.

IN 2003, HOWEVER, Cassidy received a call that would put his theories on the national map in a more significant way. It came from the Thomas More Law Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which was looking for someone to help South Dakota legislator Matt McCaulley draft a total abortion ban. This was controversial, even within the pro-life community; many abortion foes, recognizing that they didn’t have a Supreme Court majority, favored more incremental steps.

The following February, Cassidy arrived in Pierre for a committee hearing on the proposed ban. The room was stifling and standing-room only. He showed up early, according to one witness, armed with boxes of written materials to place on lawmakers’ chairs. Unlike most pro-lifers, who tended to focus on preserving unborn life, Cassidy was arguing for the preservation of women’s sanity. He had arranged for dramatic testimony from some of the women whose stories he’d been collecting. There was the rape victim who said she’d had an abortion at the urging of family and friends, and who now felt that the procedure was like a second rape, far worse than the first. Another woman spoke of attempting suicide because she felt guilty about her abortion. (Cassidy recalls her leaning over the table to show legislators the scars where she’d sliced her arms—one lawmaker had to leave the room to compose himself.) He also brought in fetal development experts and pro-life mental-health researchers to attest to abortion’s psychological hazards and the status of the fertilized egg as a complete human being. When Cassidy took the floor, he spoke of the women who had sought his assistance with adoption cases, and about returning the babies to their biological mothers. He spoke of the other women, too, explaining that “I can’t get the babies back for them because the people who violated their rights killed the babies.”

The message was no different from the one he’d been delivering for more than a decade, but unlike the judges who’d rejected his arguments, the legislators were moved. The next morning, they “hoghoused” the proposed ban—a South Dakota term for ditching a bill’s text in favor of a new version. The new text was focused more on the mother—and Cassidy’s fingerprints were evident throughout: “The state has a duty to protect the pregnant mother’s fundamental interest in her relationship with her unborn child,” it stated, adding that abortion creates a “significant risk” of severe depression, suicide, and post-traumatic stress disorders. It was the most prominent platform the “abortion hurts women” argument, and Cassidy, had ever had.

The bill, the first of a series of unsuccessful attempts by South Dakota legislators to ban abortion, was vetoed by the governor. (Two subsequent attempts were shot down at the ballot box.) But pro-life legislators were impressed by the gut-wrenching testimony Cassidy had arranged. In 2005, they created a task force to study abortion’s harmful effects. Cassidy was again called in to help, and the task force published a lengthy report citing the stories of his witnesses and recommending that abortion be banned. It was a huge moment for Cassidy and his allies: For the first time, sketchy findings about abortion’s emotional harm to women had a state’s official imprimatur.

The same year, the legislators passed South Dakota’s informed-consent law, which requires doctors to tell their patients “that the abortion will terminate the life of a whole, separate, unique, living human being”—language nearly identical to that which Cassidy used in Santa Marie. In 2011, the law faces a challenge in a case called Planned Parenthood v. Rounds. Arguing in its defense before the Eighth US Circuit Court of Appeals will be South Dakota’s attorney general—and Cassidy himself.

THE ULTIMATE goal of all anti-abortion efforts is a sympathetic hearing from the Supreme Court, and in 2007 that body gave Cassidy’s arguments an unexpected and unprecedented boost. In the majority opinon in Gonzales v. Carhart, which addressed Congress’ so-called partial-birth abortion ban, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that banning the late-term procedure could be justified by the state’s “profound respect for the life within the woman.” Kennedy acknowledged that there is “no reliable data” on whether abortion affects women’s mental health, but he nonetheless found it “unexceptionable” to conclude that some women who have abortions will suffer “severe depression” and other ills—and that they would suffer further if they underwent a “partial-birth” abortion and only later learned about the procedure’s gruesome details. In support of his position, Kennedy cited not a scientific study but rather a brief submitted by Cassidy’s allies on behalf of Sandra Cano and 180 other women. (Among other things, their brief argued that the partial-birth ban needn’t contain an exception for the woman’s health.)

In a blistering dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg chastised the court for invoking “an antiabortion shibboleth for which it concededly has no reliable evidence…This way of thinking reflects ancient notions about women’s place in the family and under the Constitution—ideas that have long since been discredited.”

The New York Times’ Linda Greenhouse called the ruling “a major departure from how the court has framed the abortion issue for the past 34 years.” The pro-life focus on abortion’s harm to women, she added, had “remained largely under the radar until it emerged full-blown in Justice Kennedy’s opinion,” and South Dakota’s law “would be unlikely to raise alarms at the Supreme Court, based on the majority opinion.”

“The chill Carhart sends down my spine,” says Roger Evans, a senior attorney for Planned Parenthood, “is that it really sets the stage for the upholding of any of these ridiculous ‘abortion hurts women’ measures.”

Cassidy, though, views Carhart as the vindication for a not-always-popular strategy. We were back at his wooden table for one last interview and I’d asked him to respond to criticism from some of his pro-life peers.

Throughout our meetings, he had always found a way to wrap up his stories with redemption: the birth mother reunited with her child; the outlawing of paid surrogacy; the unaborted child, happy and grown. During one session, he told me about running into one of the “wrongful birth” parents whose daughter has Down syndrome. Cassidy had ordered an ice cream on a New Jersey boardwalk one day, and the vendor refused his money. It was the girl’s father; Cassidy’s words, the man explained, had led him and his wife to abandon their case. “A day doesn’t go by,” Cassidy recalled him expressing, “that they don’t thank God for this little girl,” and “they thank me and thought about me all the time.”

But now Cassidy seemed tired, beleaguered, fed up with the naysayers. Chief among his concerns were critiques from prominent pro-lifers who thought that he had wasted resources by pushing the women-protection argument into legislation—and had pushed too hard for a ban in South Dakota. One of those critics was James Bopp, longtime general counsel to the National Right to Life Committee. “The court is not at all prepared to overturn Roe v. Wade,” Bopp told me. Cassidy’s effort, he added, “is not only futile, it’s also counterproductive.”

In his defense, Cassidy cited Kennedy’s opinion in Carhart. “I felt that the decision was far better than anybody could have possibly predicted. It changed the rules of engagement in abortion litigation,” he said. “If they think that it’s not effective, they’re just wrong.” He paused, and when he resumed speaking, his voice was particularly heavy. “But that’s okay. I mean, this is what happens. When Galileo said that the Earth revolves around the sun, he was castigated for it.”

—-

Harold Cassidy responds to this article (PDF).