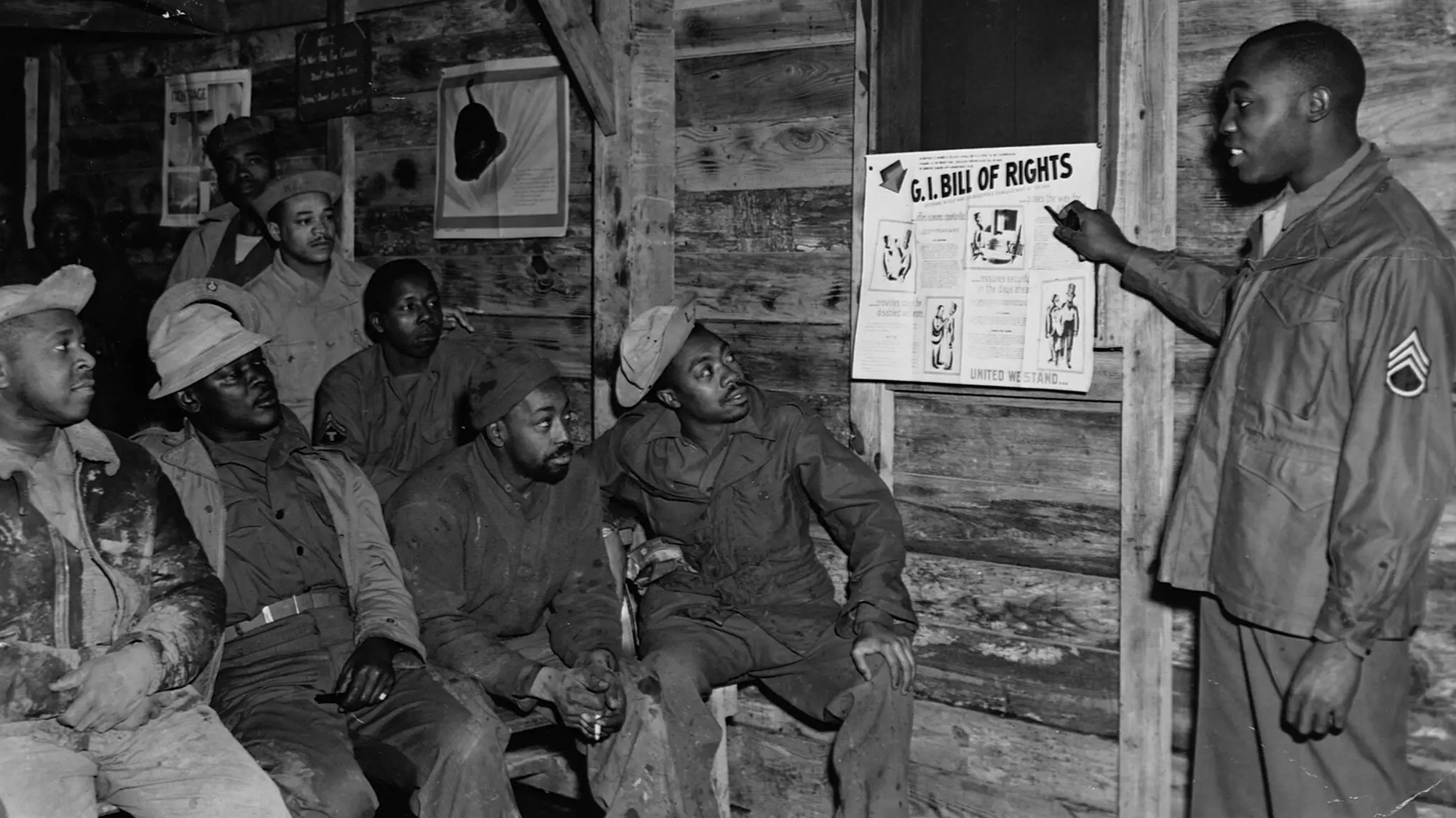

In August 1944, just two months after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (a.k.a. the GI Bill of Rights), Harry McAlpin, Washington correspondent for the National Negro Publishers Association, warned that the new law, though race-neutral on its face, would exclude Black veterans. The GI Bill included funding for housing, college, and job training, along with business loans and unemployment insurance, which fueled social mobility for millions of veterans and their descendants. It also included “innumerable loopholes for states to ‘rob’ returning Negro veterans of the rights and privileges they have earned by risking their lives and limbs for the preservation (?) of democracy,” McAlpin wrote.

This piece is adapted from Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad (Out October 18 from Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC, all rights reserved).

Author photo by Eli Burakian

This discrimination was by design. Southern Democrats including House Veterans Committee Chairman John Rankin—who a quarter century earlier had penned an editorial ridiculing the notion that military service might somehow elevate a Black man to become the “peer of the white man”—took pains to ensure that the bill’s benefits would be administered at the state level, where white officials served as gatekeepers.

Sure enough, at their local United States Employment Service job centers, Black veterans encountered white counselors who routinely shunted them into unskilled jobs, even if they had military training as carpenters, electricians, mechanics, or welders. In Mississippi, white veterans received 86 percent of the skilled and semiskilled positions, while Black vets filled 92 percent of unskilled and service-oriented jobs. In Birmingham, Alabama, a USES counselor told Willie May, who had maintained communication lines in the Army Signal Corps, that there were no suitable positions available, even though the counselors had placed several white Signal Corps vets with the Birmingham Power Company. May settled for work as a Pullman porter, which paid far less.

This gun crew was given the Navy Cross for maintaining their posts after their ship was damaged by enemy fire.

Department of Defense/National Archives

This was an extension of the second-class treatment Black Americans endured as servicemembers, confirming the dreadful suspicion that the freedoms they labored to protect overseas would not be forthcoming at home. As I document in my new book, Half American: The Epic Story of AfricanAmericans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad, from which this essay is adapted, Black volunteers and draftees formed the backbone of a supply effort critical to the Allied victory, and fought courageously in combat when given the opportunity—but were often assigned positions of grunt labor and servitude, building roads and infrastructure or cooking and cleaning for white officers and enlisted men. Black troops nevertheless risked their lives for a segregated military that regarded them with such contempt that, after the Nazis surrendered, US officers let released German POWs socialize and dine alongside white soldiers in areas still off-limits to Blacks.

T-5 William E. Thomas and Pfc. Joseph Jackson, photographed on an Easter morning during the war.

Department of Defense/National Archives

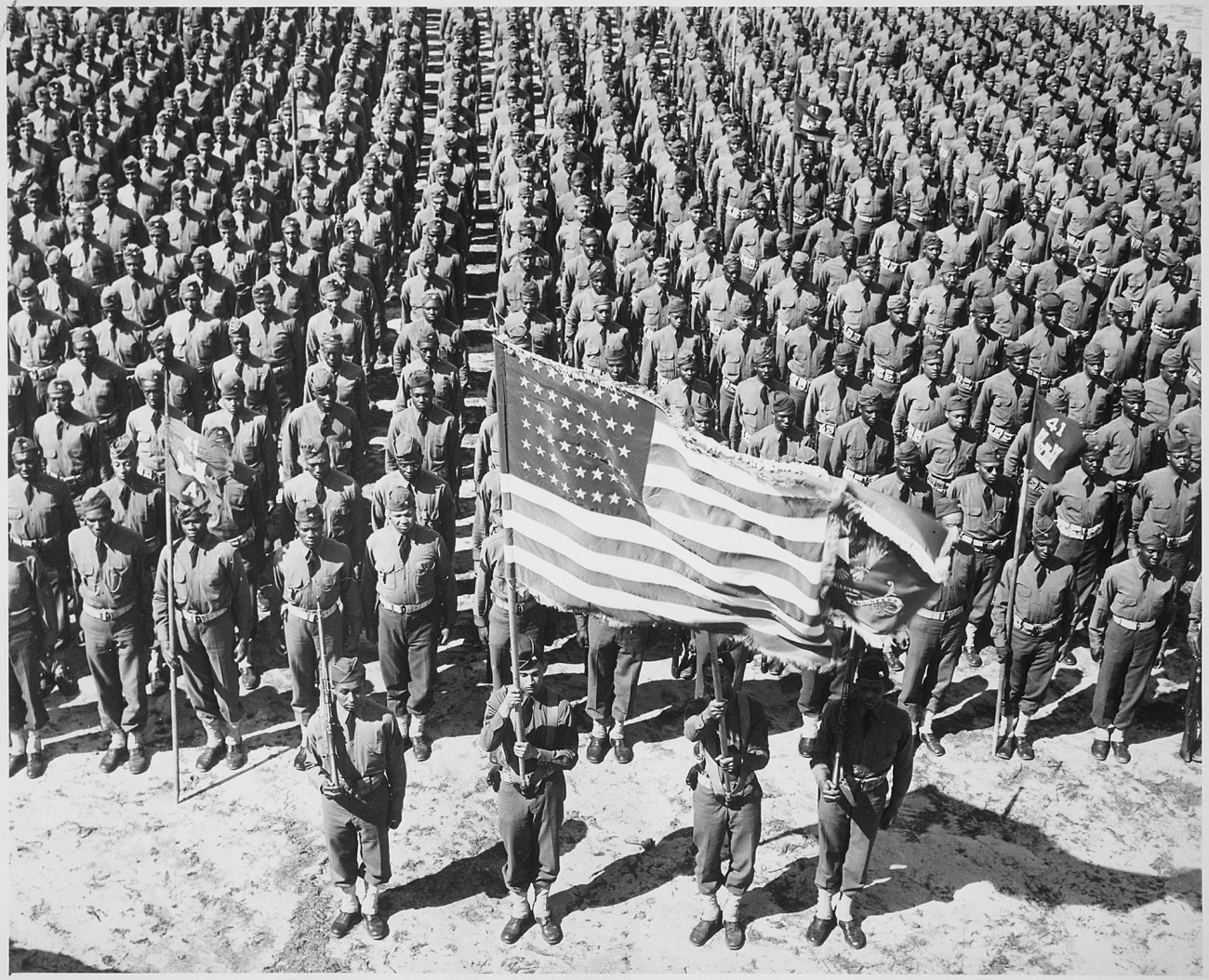

The 41st Engineers perform a color guard ceremony at Ft. Bragg, NC.

Office for Emergency Management/National Archives

Adding insult to injury, Black veterans returned to a nation less than thankful for their service. White officers and publications belittled or simply ignored Black contributions to the war effort. In the South, Black vets were targeted—and sometimes lynched—by white mobs eager to remind them of their place in the pecking order. Black newspapers printed weekly accounts of violence against vets, many of whom were attacked while in uniform.

Yet perhaps even more pernicious were the discriminatory policies of the state, whose ill effects on the Black community spanned generations. Black veterans, like their white comrades, sought out low-interest mortgages and loans, guaranteed by the Veterans Administration, to buy homes and start businesses. Some succeeded, but the vast majority were turned away by the nation’s banks, whose racist lending practices were unfettered by the GI Bill. “Loans to Negro veterans are almost out of the question,” the National Urban League observed.

The law, in other words, exacerbated the segregation created and maintained by federal mortgage redlining and white housing covenants. In Mississippi, only two of the more than 3,200 VA-guaranteed home loans issued in 1947 went to Black borrowers.

Things weren’t much better up north. Of 67,000 mortgages insured by the VA in the New York and northern New Jersey suburbs that year, fewer than 100 went to nonwhites. Nationally, by 1950, white veterans had received nearly 98 percent of the VA-guaranteed loans.

Black veterans who managed to get a loan, moreover, faced organized resistance and violence from white homeowners. Just south of San Francisco, white neighbors threatened Army veteran John T. Walker before burning down his newly built home. Across the country, returning servicemembers encountered racial covenants that explicitly blocked them from owning or renting in white areas. A subdivision built for veterans in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was designated whites-only. In Seattle, a covenant restricted the sale of property to “persons of the Aryan race”—that was in 1946, one year after the Allies defeated the Nazis with the help of more than 1 million Black servicemembers.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion in France.

Department of Defense/National Archives

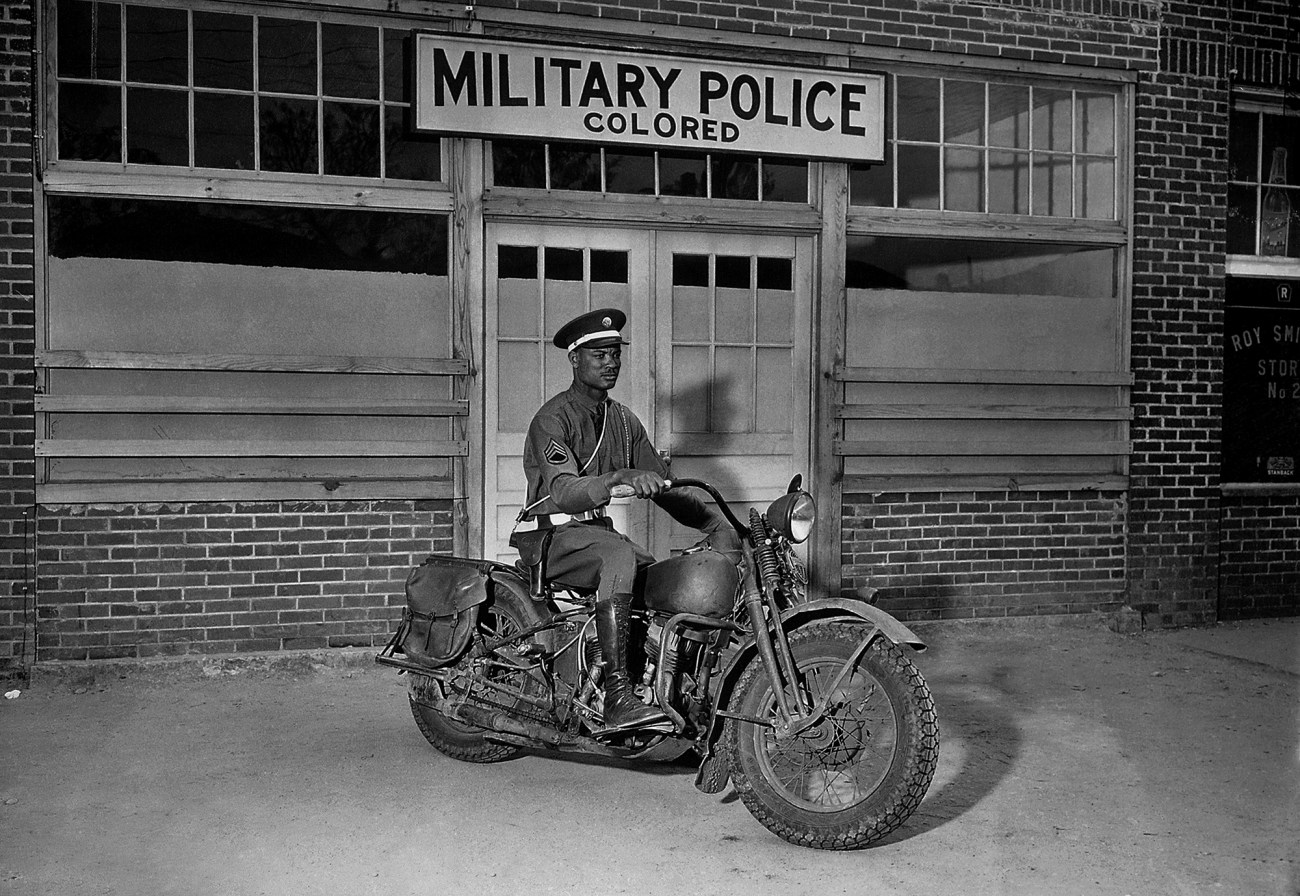

An American MP stands ready in Columbus, Georgia.

Department of Defense/National Archives

The upshot: Black veterans were almost completely locked out of the postwar housing boom and the ability to accrue property equity—the primary conduit by which American families generate wealth and pass it to future generations.

The GI Bill also enabled millions to attend college, but here again the opportunities differed dramatically along racial lines. Colleges in the North and West admitted only a token few Black students, and Black vets faced interference from racist VA counselors, whose signoff was required to use GI Bill funds for tuition, room, and board.

When Tuskegee Airman Monte Posey went to a Chicago VA office for approval to attend the University of Illinois, his counselor insisted there were no professional opportunities for college-educated Black people. Rather than waste time at a university, Posey should sign up for vocational training. (Posey persisted and attended college for two years before leaving to seek full-time work, ultimately as a police officer.)

In the South, higher education was legally segregated and white colleges outnumbered Black ones by more than five to one, even though a quarter of the region’s population was Black. The Black colleges, though dedicated, were chronically underfunded and unequipped to deal with unprecedented demand from servicemembers hungry for a degree. By 1947, as many as 50,000 qualified Black veterans had been turned away.

All told, 28 percent of white veterans went to college on the GI Bill vs. just 12 percent of Black veterans. So while the legislation did help thousands of Black families take their rightful place in the rising postwar middle class, its discriminatory application significantly widened the overall educational and economic gaps between Black and white Americans. “The veterans’ program,” concluded the Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper, “completely failed veterans of minority races.”

Maintaining the air cleaner of an Army truck in Fort Knox, Kentucky.

Alfred T. Palmer/Library of Congress

In 1945, during Operation Fire Fly, the Black paratroopers of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion made more than 8,000 individual jumps to fight wildfires in the Pacific Northwest. Here they are preparing to jump from a Douglas C-47 on a wildfire in Wallowa Forest, Oregon.

Department of Defense/National Archives

Making matters worse, the military doled out so-called blue discharges—after the colored paper on which they were printed—to more than 10,000 Black servicemembers, rendering them ineligible for benefits. A blue discharge had many of the practical effects of a dishonorable discharge, but could be issued by officers without a court-martial or legal proceeding, and soldiers who were deemed “troublemakers,” rightly or wrongly, were pressured into accepting a blue ticket.

The Pittsburgh Courier called the policy a “vicious instrument,” and warned of “a widespread conspiracy to give blue discharges to as many colored soldiers and sailors as possible.” Black servicemembers made up less than 7 percent of armed forces personnel, but received 22 percent of the blue discharges from December 1941 through June 1945. That fall, the Pittsburgh Courier advised Black servicemen to reject the blue tickets, and published instructions on how to appeal them.

Researchers from the Institute for Economic and Racial Equity at Brandeis University recently calculated that the GI benefits secured by Black individuals were worth, on average, 40 percent of those whites received. This produced long-term disparities, the study found. By the time WWII veterans hit the age range at which wealth typically peaks, the median net worth of Black veteran households was $100,000 less than that of white ones.

Black Marines aboard a Coast Guard transport in the Pacific.

Department of Transportation/National Archives

Revisited through the lens of race, the GI Bill, long hailed as a powerful engine of class mobility for the Greatest Generation, loses some of its luster. Like the Homestead Acts of the late 1800s, also nominally race-neutral, the legislation harnessed immense public resources to bolster the private wealth of a favored group.

WWII veterans received more than $50 billion under the GI Bill, all told, and the exclusion of Black Americans from the spoils helps explain the vastness of the racial wealth gap today. As of 2019, the median wealth of Black families in the United States was less than 15 percent that of white families—$24,100 vs. $188,200. Black homeownership stood at about 45 percent vs. 75 percent for white Americans. And white families were nearly three times as likely as Black families to have received an inheritance.

The other way the GI Bill fundamentally shortchanged the nation involves opportunity cost. Black Americans who could take full advantage of the GI Bill often went on to do amazing things. Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps veteran Dovey Johnson Roundtree attended Howard University law school, established a law firm in Washington, DC, and then, in a landmark 1955 civil rights case, Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, helped secure a ban on racial segregation in interstate bus travel. Robert P. Madison was in the 92nd Infantry Division and earned a Purple Heart in combat in Italy. After the war he leveraged the GI Bill to earn architectural degrees from Case Western and Harvard before establishing a trailblazing firm in Cleveland, where he helped design the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

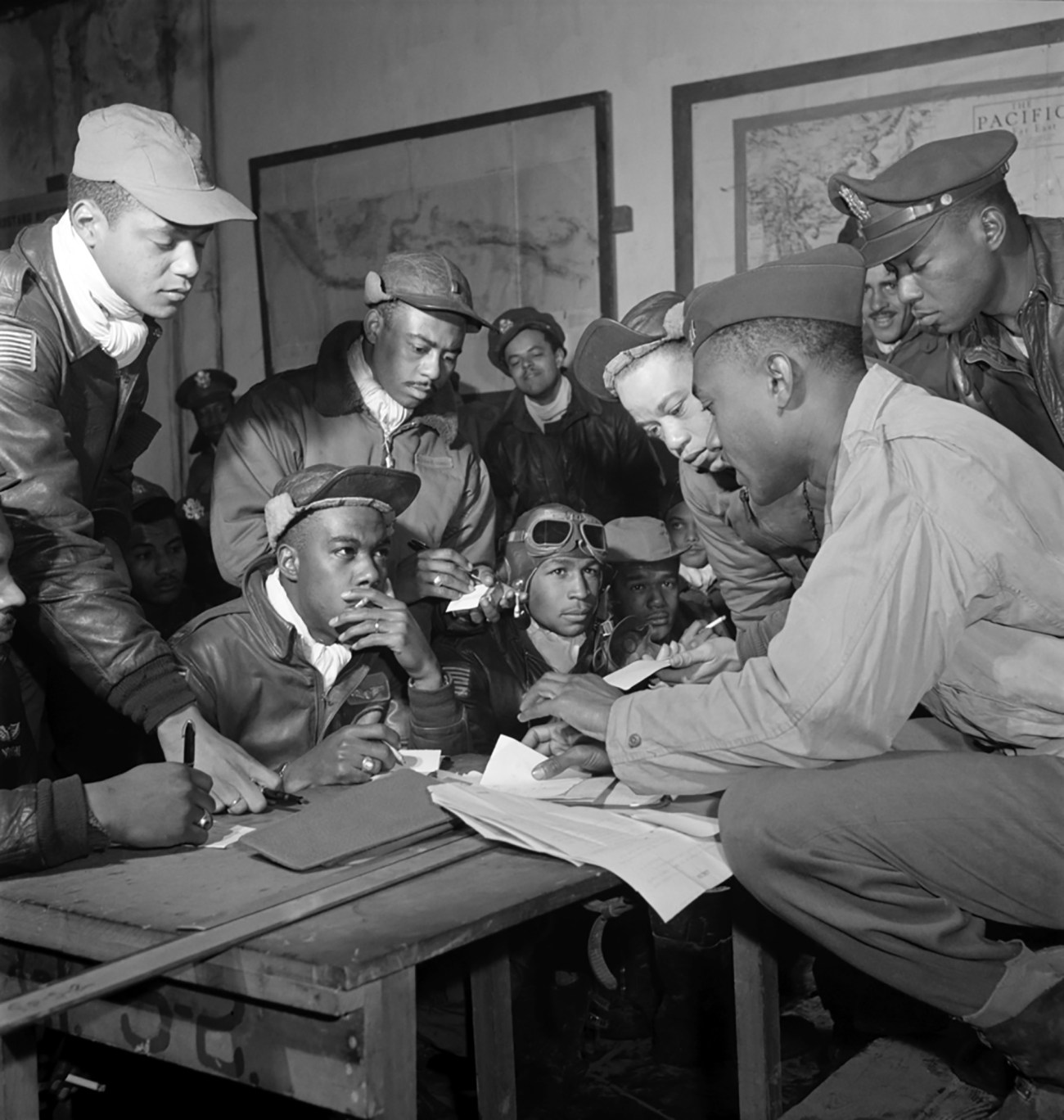

Members of the 332nd Fighter Group at a briefing in Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945.

Toni Frissell/Library of Congress

These examples only hint at the tremendous cost of excluding Black families from GI benefits. Had all the men and women who dedicated their labor, skills, and courage to the war effort gotten their due, America might today have tens of thousands more Black doctors, lawyers, engineers, professors, economists, scientists, software designers, etc.

Last Veterans Day, in light of this history, Reps. Seth Moulton of Massachusetts and James Clyburn of South Carolina, and Sen. Reverend Raphael Warnock of Georgia introduced the GI Bill Restoration Act, which directs the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to extend further housing and education assistance to the surviving spouses and direct descendants of Black WWII vets.

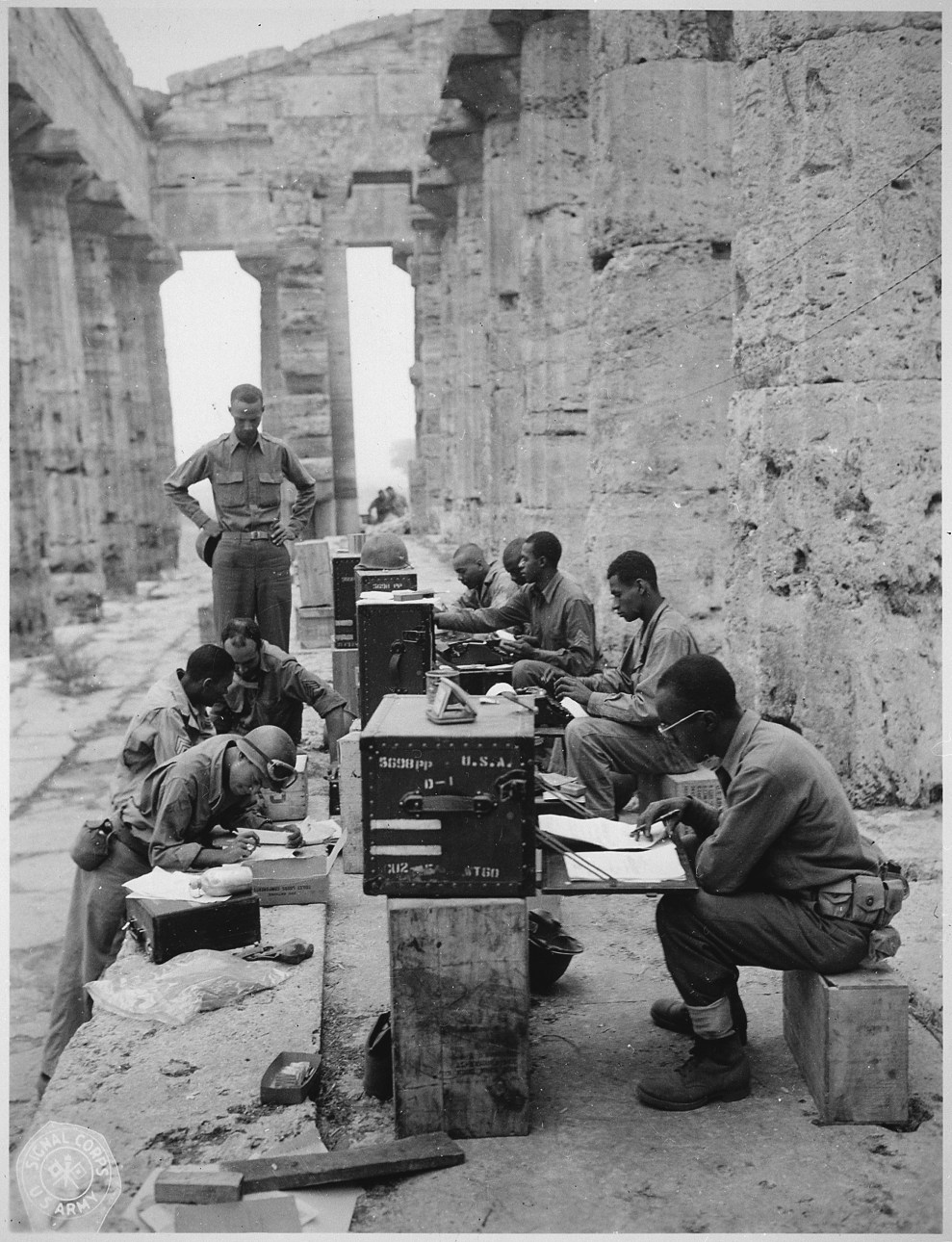

Members of the Headquarters Company, 480th Port Battalion, at the ancient Greek Temple of Neptune.

Department of Defense/National Archives

The legislation remains mired in the House and Senate Veterans’ Affairs committees, where it has yet to receive a hearing. Republican lawmakers view it as partisan because it asks them and their constituents to grapple with the legacy of structural racism in America, a subject most would prefer to ignore. Indeed, key committee members have been on the front lines of the culture war against critical race theory, among them Rep. Jim Banks (R-Ind.), who last year urged colleagues to ban the discussion of racism in public school classrooms.

The Senate Veterans’ Affairs committee includes Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.), John Boozman (R-Ariz.), Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), and Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.), co-sponsors of the Saving American History Act, which would abolish federal funding for schools that teach the 1619 Project or critical race theory.

“Enacting meaningful legislation is often a marathon, not a sprint,” Clyburn told me in a statement provided by his staff. The GI Bill Restoration Act is competing with other priorities, but “I am committed to working as hard as I can, for as long as I can, to see that the survivors and/or direct descendants of Black World War II veterans realize the promise of the GI Bill denied to their families due to institutionalized discrimination.”

Women’s Army Corps officers inspect the 6888th Central Postal Director Battalion.

Department of Defense/National Archives

Tuskegee airmen at Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945.

Toni Frissell/Library of Congress

“Black WWII veterans were robbed of what should have been life-changing opportunities,” Moulton added in his own statement. “Not enough Americans realize this—or that surviving veterans and millions of their descendants continue to feel the repercussions today. We introduced this bill not because we knew it would be politically or logistically easy to get passed, but because this is a national conversation that is painfully overdue. We’re under no illusions that moving this bill forward will happen overnight.”

The act is officially named in honor of Sergeant Joseph Maddox, whom the VA denied benefits for a master’s degree program at Harvard University to “avoid setting a precedent”—only after the NAACP went to bat for him did the agency relent—and Sergeant Isaac Woodard Jr., a Pacific theater veteran who was still wearing his Army uniform en route to rejoin his family when he was brutally beaten by white police in Batesburg, South Carolina. His eyes were gouged out by a sheriff’s nightstick, blinding him for life.

“Negro veterans that fought in this war don’t realize that the real battle has just begun in America,” Woodard told the Chicago Defender soon after the attack. “They went overseas and did their duty and now they’re home and have to fight another struggle that I think outweighs the war.”