George Floyd protesters shut down the westbound lanes of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge on June 14, 2020.Chris Tuite/ImageSPACE/MediaPunch/IPX

Smile. If you’re in downtown San Francisco’s business district, you’re in view of Motorola cameras so sharp they can pick out the color of your eyes, the marks on your face. San Francisco cops used the footage to identify and arrest one man whom camera operators could see so clearly they nicknamed him “Dimples.” Then the police used the cameras to monitor protests against the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. And then they got in trouble.

Today, the city of San Francisco was sued in California Superior Court by three locals who took part in anti-police-violence protests. Hope Williams, Nestor Reyes, and Nathan Sheard allege that city police violated their civil rights and broke the law by using the privately owned cameras’ live feed to carry out dragnet surveillance of protesters.

They’re being represented by the ACLU of Northern California and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital civil liberties group based in the city. The suit seeks a judgment that the police broke city laws requiring local law enforcement to not “acquire, borrow, or use any private camera network” without approval from the city’s Board of Supervisors.

Residents were promised more restraint when the camera network, which now covers 135 blocks, was set up. “The police can’t monitor it live,” cryptocurrency mogul Chris Larsen assured San Francisco’s ABC7 News earlier this year. “That’s actually against the law.”

Why is a venture capitalist opining on the cameras to begin with? Larsen is responsible for them. A San Francisco native, he funded the initial placement of the cameras and the “business improvement districts” that monitor them, assuring city officials and concerned citizens that he took their privacy concerns seriously. Police…did not, the lawsuit alleges.

Records reveal that SFPD’s Homeland Security Unit obtained real-time access to the cameras on May 31, as major protests were taking off in the city, and requested a five-day extension on June 2, which it received. The cops also received real-time access to the cameras to monitor gatherings for the Fourth of July, the Super Bowl, and San Francisco’s 2019 Pride Parade, according to the San Francisco Examiner. (The cameras are disproportionately concentrated in shopping districts and adjacent low-income neighborhoods.)

Under San Francisco’s Surveillance Technology Ordinance, police need approval from the city’s Board of Supervisors to acquire and use new surveillance technology. The ordinance provides exceptions for “an emergency involving imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to any person.”

SFPD argues that its use of the cameras met the “imminent danger” standard; ACLU of Northern California attorney Matthew Cagle calls SFPD’s argument “a power grab that defies the law and brushes off the democratic checks on their power.”

“It was a tactic to provoke fear,” says plaintiff Hope Williams, and “an absolute, blatant disregard of the Surveillance Technology Ordinance in San Francisco.” Williams says she had a “visceral reaction” to finding out about police surveillance of the protests: “What troubles me the most is how this would affect the movement.”

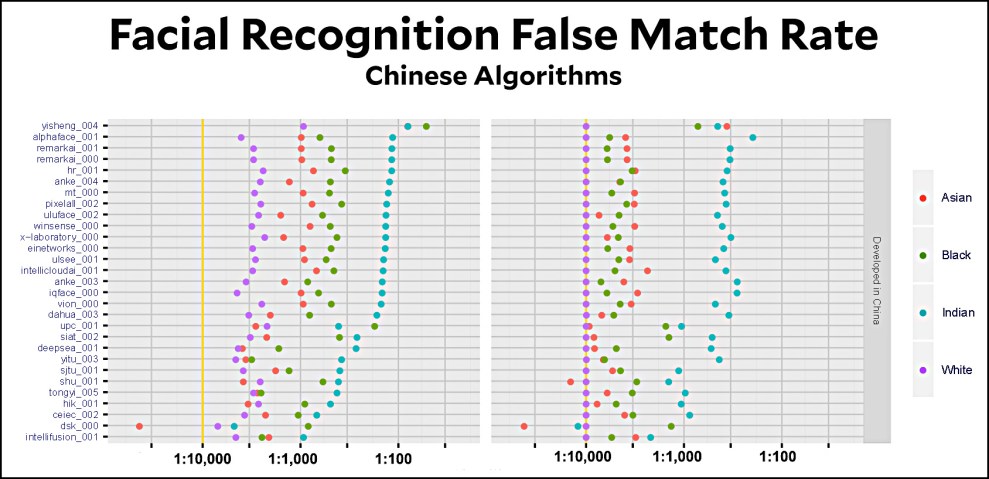

Police nationwide have been quick to jump on surveillance technologies as they become available. Generous police budgets, on the rise despite a growing protest movement, allow departments to stock up on devices that track movements, listen in on calls, and even monitor biometric responses—a digital companion to police militarization. Tech firm Clearview AI, the subject of a HuffPost profile that alleged the company had employed open white nationalists, claims that “over 2,400 law enforcement agencies” have licensed its facial recognition software, often without outside oversight.

“Surveillance technology expands police power in a very dangerous way,” Cagle says. “That’s one of the reasons that San Francisco passed an ordinance. Just the other day, we found that they had illegally used facial recognition.”

(Larsen, the venture capitalist behind the cameras, says they don’t use facial recognition technology. “We’re strongly opposed to facial recognition,” he told the New York Times in July, calling it “too powerful given the lack of laws and protections.”)

San Francisco police, like their counterparts across the country, have scaled up conventional intelligence-gathering efforts to include a new array of tools for breaking into mobile phones, tapping into wireless communications, monitoring gatherings from the air, and automatically scanning license plates.

The city, long a home of left activism, has given police plenty to surveil. The department’s intelligence unit amassed over 10,000 files, beginning in the 1970s and covering everything from South African divestment protests to AIDS crisis protests, queer liberation protests, and student sit-ins at San Francisco State University. (One San Francisco police inspector, the lawsuit notes, was caught selling SFPD files on anti-apartheid protesters to South Africa’s government.) But new technologies, and cooperative business interests, have radically expanded their reach.

Even surveillance spending that appears tough to argue with—like ShotSpotter, an audio surveillance network meant to detect gunfire—can cost far more than shoe-leather policing and still produce few results. From the beginning of 2013 to June 2015, an 18-month period, ShotSpotter issued more than 4,300 alerts in San Francisco. They yielded two arrests.

Surveillance of protests, though, has led to arrests. Since May, police in Texas, Washington, and New York have harnessed surveillance technology to track down protesters on a variety of questionable charges. In Texas, state officials used surveillance footage to arrest a 25-year-old Black man despite an affidavit that “didn’t portray him engaging in any illegal behavior.” At least a dozen other Texans were arrested in that round of surveillance-based investigations.

Cases like those are part of Cagle’s concern. “If this is left unchecked,” he says, “surveillance networks will radically expand the police’s presence exactly at a time when we’re having a public conversation about these police departments and the power that they have.”

The San Francisco Police Department referred Mother Jones to the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office. We’ll update if we hear back.