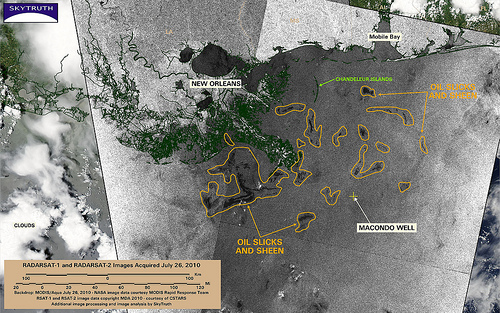

Photo courtsey of RADARSTAT, <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/skytruth/4835566748/">via SkyTruth's Flickr feed</a>,

First there was the bizarre AFP report asking where all the oil in the Gulf could have possibly gone. Then a breaking news alert from the New York Times landed in my inbox Tuesday night declaring “Gulf of Mexico Oil Slick Appears to Vanish Quickly,” which seemed to imply that because a few reporters hadn’t noticed much crude on a flyover, it must have magically disappeared. (The alert failed to mention the 1.8 million gallons of dispersant that BP dumped on the spill to do exactly that).

Today we have yet another example of the news media promoting the idea that the Gulf disaster might not be all that bad after all, with Time‘s big piece, “The BP Spill: Has the Damage Been Exaggerated?“

The story starts out by offering Rush Limbaugh as a voice of reason on the disaster against all the “end-is-nigh eco-hype,” even while calling him an “obnoxious anti-environmentalist.” That should give you a sense of where the story is heading. And then it goes there:

Well, Rush has a point. The Deepwater explosion was an awful tragedy for the 11 workers who died on the rig, and it’s no leak; it’s the biggest oil spill in U.S. history. It’s also inflicting serious economic and psychological damage on coastal communities that depend on tourism, fishing and drilling. But so far — while it’s important to acknowledge that the long-term potential danger is simply unknowable for an underwater event that took place just three months ago — it does not seem to be inflicting severe environmental damage. “The impacts have been much, much less than everyone feared,” says geochemist Jacqueline Michel, a federal contractor who is coordinating shoreline assessments in Louisiana.

In short, the story is classic man-bites-dog, knee-jerk counterintuitivism. In reality, we have no idea yet how bad the damage in the Gulf is. The federal government is still only in the early stages of a natural resources damage assessment, a process to determine the full extent of the destruction. The government hasn’t even come up with an estime of how much oil leaked into the Gulf. And BP hasn’t yet finished the relief wells, meaning the disaster isn’t over yet. Meanwhile, the environmental impacts of the natural gas that has also been seeping into the Gulf remain unclear. And the article gives scant attention to the nearly 2 million gallons of dispersant applied by BP to break up the spill, which the country’s top environmental official has acknowledged is a science experiment of monumental proportions.

“The amount of oil and toxic dispersant pumped into the Gulf is unprecedented, and we know the marine impacts will be massive, we simply don’t know how long it will take for the ecosystem to rebound, and how significant the decrease in productivity will be until it recovers,” says Aaron Viles, campaign director at the Gulf Restoration Network.

Referring to the Time article’s author, Michael Grunwald, National Resources Defense Council lawyer David Pettit says, “I’m not sure what boats he’s been out on. When I went out from Plaquemines Parish two weeks ago, there were oiled marshes as far as the eye could see, plus all the islands we saw were oiled. I would agree that it’s too early to say what the long-term effect of that oiling will be, but by the same token I don’t think anyone can credibly say that there will be little or no effect.”

The article mentions the 488 dead sea turtles found in the Gulf, but says “only 17 were visibly oiled.” What it doesn’t mention, however, is that nearly 80 percent of those dead turtles are Kemp’s Ridley turtles, the most endangered species of sea turtle in the world. “When you get to that level of peril, every individual makes a difference,” says Doug Inkley, a wildlife biologist with the National Wildlife Federation who was in the Gulf last week. Nor does a turtle need to be visibly oiled to die because of it; ingesting the oil, and the oil-dispersant mix, can also be deadly. And then there are the turtles that may have been burned alive.

I have quite a bit of respect for Grunwald, whose work on the Army Corps of Engineers and Hurricane Katrina was spectacular. But if he’s going to criticize folks for making premature doomsday predictions, then he, too, shouldn’t engage in making preemptive declarations that the problem is exaggerated, either. Doing so not only lets BP off the hook, but also contributes to the already waning interest in the disaster among the American public—nothing to see here, folks, back to your regularly scheduled environmental apathy.

Real understanding of the impacts will take quite some time, but will anyone be paying attention then? More than twenty years after the Exxon Valdez disaster, fisheries have not recovered and visitors can still find crude on the shores of the Prince William Sound. Tar balls still cling to coral reefs in the region near the 1979 Ixtoc blowout off the coast of Mexico. This isn’t going away any time soon.

“The oil industry, which is arguably one of the most profitable industries in the game, took away major assets that belonged to others,” say Jackie Savitz, director of pollution campaigns at the oceans advocacy group Oceana. “Lives, jobs, livelihoods, food, and a healthy ecosystem. Whether or not it’s ‘the end’ or ‘doomsday’ isn’t the issue and it never has been.”