Activists stand with signs at an abortion-rights rally at Supreme Court in Washington to protest new state bans on abortion services on Tuesday May 21, 2019.Congressional Quarterly/Newscom/ZUMA

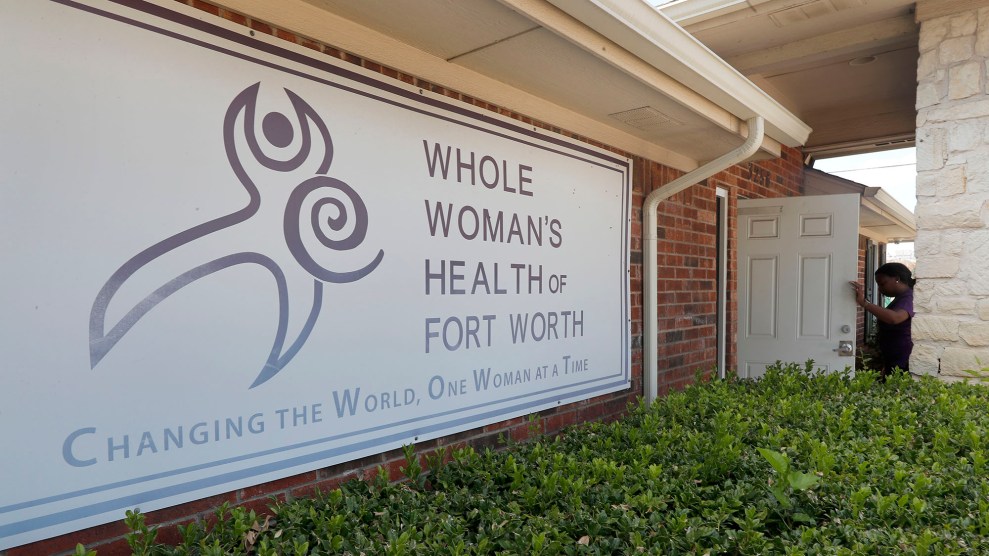

Leave it to anti-abortion politicians in Texas to not let a crisis go to waste. The state has been at the forefront of the abortion wars for just about as long as they have existed in the United States, from Roe v. Wade to Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. Now, while clinicians in the state grapple with the uncertainty of providing care in the middle of a pandemic, they are also being forced to fight for the right to keep their doors open as the state tries to quite literally shut them. The state government is claiming abortion is not an “essential” service and that it saps medical resources from physicians who need them to combat the coronavirus.

The legal ping-pong playing out over the past week has been dizzying, even by the standards of abortion litigation. It started a week ago, when Gov. Greg Abbott issued an executive order stating that abortions must be put on hold unless the pregnancy endangers the life of the pregnant person. (In some clinics, medication abortion continued, as it was not specifically banned in the order.) Abortion providers quickly sued and, a few days later, on Monday, March 30, a federal judge granted a temporary restraining order. “Regarding a woman’s right to a pre-viability abortion, the Supreme Court has spoken clearly,” the judge said in his order, pretty openly dismissing Texas’ move. “There can be no outright ban on such a procedure. The court will not speculate on whether the Supreme Court included a silent except-in-a-national-emergency-clause in its previous writings on the issue.” A hearing on a permanent injunction was scheduled for April 13.

But the next day, Tuesday, March 31, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals granted a stay, effectively halting abortion once more in Texas. And this time, for good measure, medication abortion is specifically mentioned as being prohibited.

Care has been thrown into chaos. Planned Parenthood of Greater Texas said it was forced to cancel 261 procedures last week; Amy Hagstrom Miller, president and CEO of Whole Woman’s Health, told Mother Jones that her three Texas clinics turned away at least 150 patients while the initial abortion order was in place. A couple of those patients are minors, who she said “went to a really troubled place.” She told me one woman was turned away because of the order after she drove 250 miles to seek abortion care. She refused to leave the clinic, instead pledging to stay in the area until she was able to get her abortion. Eventually, she traveled to a clinic in Colorado; she and a friend drove nonstop to get there, crashing in an Airbnb that they tried to disinfect as best they could before falling asleep. The next day, they drove back to Texas.

Hagstrom Miller, who has an easy laugh even under dire circumstances, sounded exhausted and frustrated when we spoke last week. It’d clearly been a rough few days. Last Monday night, her team made calls to pregnant people who had appointments scheduled in their Texas clinics to let them know their procedures were canceled, at least for the time being. “People were sobbing, people were begging for us to see them anyway,” she recounted. “‘Can’t you just figure this out?’; ‘What am I going to do?’; ‘Where am I going to go?'” Making those phone calls and hearing the desperation in the voices of would-be patients was gutting, she said. “We’re really concerned about these people’s mental health—it’s palpable,” even through the phone.

Now, her staffers have to make the calls all over again. “It’s absolutely cruel to say to somebody, ‘You have to continue your pregnancy against your will when there’s a pandemic,'” Hagstrom Miller said. “Those patients are just heartbroken.”

“Knowing that people that are trying to access the abortion care they need right now had an appointment, and the next day, they had to cancel their appointment, and then they had it again, and now they have to cancel it again is awful,” agreed Aimee Arrambide, executive director of NARAL Pro-Choice Texas. “Especially considering we’re in a time of economic uncertainty like a public health crisis.”

The pandemic means that in addition to unplanned pregnancies and the obstacles Texas already has in place that make it incredibly difficult for women to get abortions—like a 24-hour waiting period and medically inaccurate, state-mandated counseling—many people are dealing with job loss, as well as financial and social instability. “So many of [the women seeking abortions] are low-income. They are parenting, caring for their families. Many of them have lost jobs and wages because of the pandemic, working at restaurants or bars or retail businesses that are closed. Whatever the situation is, they’re now without income,” said Amanda Beatriz Williams, executive director of the Lilith Fund, the state’s oldest abortion fund, which primarily serves women in central and southeastern Texas.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, meanwhile, called Tuesday’s ruling a “victory.”

It’s frightening but not unreasonable to wonder if Texas is providing a blueprint for other states that have sought to ban abortion in the past. Indeed, a handful of other states are also fighting legal battles over whether abortion care constitutes “essential” health care in this moment. Ohio and Alabama have garnered temporary restraining orders that allow clinics in those states to remain open, but Oklahoma, Iowa, Louisiana, and Mississippi are in limbo, subject to orders made by their governors that abortion is not essential and therefore cannot continue. This could all come to a head very soon, given that Texas is likely headed to the US Supreme Court for an emergency ruling, said Mary Ziegler, author of Abortion and the Law in America: Roe v. Wade to the Present. Abortion bans in this country have never survived challenges in the lower courts, but now, “in terms of what a state without abortion looks like, we’ll know imminently,” she warned.

In the meantime, abortion funds in Texas are scrambling to redirect their clients to clinics in other states, even as Gov. Abbott ordered Tuesday that people should “minimize” contact by staying home. “It’s kind of hard to do planning, because we don’t necessarily know what the end of the week will look like, or apparently the end of the day, the next 24 hours,” said Stephanie Gómez, a board member at Fund Texas Choice. As Gómez points out, sending pregnant people across state lines puts them at risk of infection and increases the potential spread of the coronavirus, though she noted that the fund is instructing its clients to follow CDC guidelines to the best of their ability while traveling significant distances. The majority of Texas counties are at least 200 miles away from the nearest out-of-state abortion provider, according to an analysis by the Texas Policy Evaluation Project.

“It’s a hard situation made worse,” said Williams from the Lilith Fund. Identifying and building relationships with more out-of-state clinics is a major priority for her and her colleagues this week, though she worries that a new influx of patients will overwhelm states where abortion is still accessible.

Worse still, the state has still not fully recovered from a 2013 omnibus bill restricting abortion that ultimately led to the Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt Supreme Court case. Before that bill became law, Texas had more than 40 health care centers where abortion could be accessed. Now, there are only 22. And in this moment, those facilities face an uncertain future as the public health crisis escalates. Hagstrom Miller told me last week that she’d been forced to lay off staff since Abbott’s initial order. “It’s crazy, trying to keep our clinics open,” she said. “We have so many people calling and needing services, and services are disrupted. It’s like a 400-level Chutes and Ladders.”

As a health care provider and also a small business owner, Hagstrom Miller said she’s feeling the pressure “keenly.”

“So many of us who have small businesses all over the country are just in peril—what support is there for us to take care of our staff in a situation like this?” she said. “Then for me as a health care provider, what a horrible time to bring abortion politics into this mix when my staff are nurses and medical assistants and doctors, who are frontline essential workers right now, and they should be given respect for being willing to put their lives on the line to take care of people instead of having to wade through this political nonsense.”