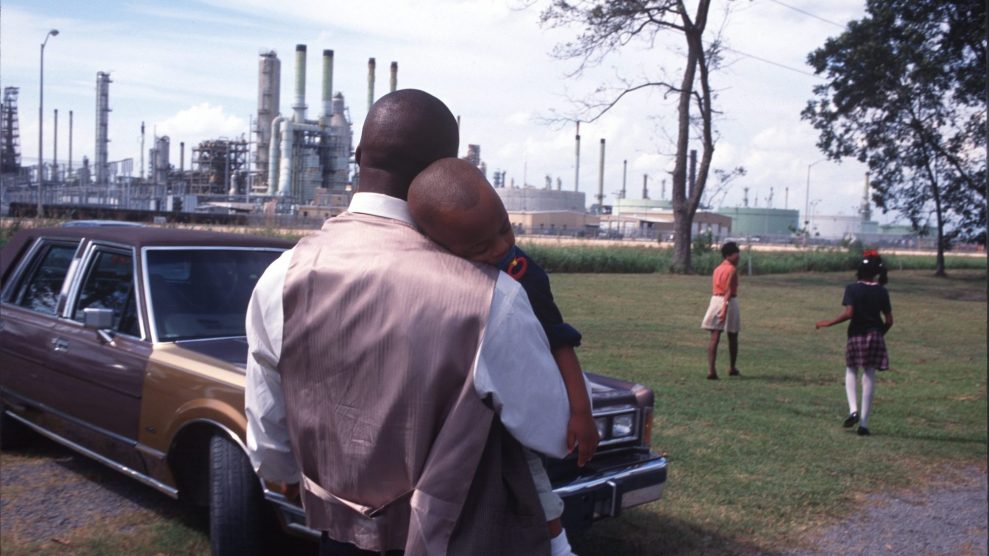

A family leaves Sunday church services surrounded by chemical plants in Lions, Louisiana.Andrew Lichtenstein/Getty

This piece was originally published in Grist and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

More than 50 years ago, despite a storm that was brewing in Memphis, an overflow crowd of hundreds gathered to hear a rousing speech from Martin Luther King, Jr., who encouraged the city’s striking sanitation workers not to give up their struggle for safer working conditions and better wages. “Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point,” he told them, in what would turn out to be his last speech.

King saw the workers’ quest as one that aligned with his national Poor People’s Campaign. When King spoke of a human rights revolution, he spoke broadly of seeking justice for people living in slums, for hungry children, and for the disenfranchised. He was fighting so that everyone could one day have a safe place to live, work, and play. He wanted “massive industries” to treat people right. “The nation is sick, trouble is in the land, confusion all around,” King said that spring night in 1968. He could have easily been speaking about the United States in 2020.

In the decades that followed, environmental justice advocates told us to pay heed to these same communities that King died trying to help. We were warned that the storm was coming. The environmental movement, they said, should reckon with the disproportionate effects of environmental contamination—from petrochemical facilities, landfills, waste incinerators, oil refineries, smelters, and freeways—on low-income residents and communities of color.

Then, the novel coronavirus struck.

Now, as skyrocketing unemployment is predicted to increase poverty rates and widen racial disparities, these same communities find themselves in the crosshairs of COVID-19. In Chicago, African Americans represent 60 percent of the city’s COVID-19-related deaths, despite only comprising 30 percent of the city’s population. African Americans in states such as Michigan, Illinois, and Louisiana have also been disproportionately killed by COVID-19—and early data suggest the disparity could be widest in the South.

Across the country, Latinos are also feeling the brunt of the virus, with health experts particularly worried that overcrowded housing, lack of health insurance, and workplace exposure in jobs like agriculture will cause the number of cases to skyrocket. And in the Navajo Nation the numbers are grim as well, with a positive test rate that is nine times that of the rest of Arizona. Underlying issues there, including a lack of access to safe drinking water and an underfunded health care system, are putting many at risk.

The disparities send a clear message: The COVID-19 pandemic is not just a health crisis, it’s an environmental justice crisis.

Over the past month, I’ve seen in my reporting why many of these populations are so vulnerable: Farmworkers toil in unsafe conditions before returning home to overcrowded mobile homes, apartments, and houses where they cannot self-isolate. Residents who live near or work in warehouses in the nation’s logistics hubs already suffer fragile respiratory health conditions—conditions that will only worsen as pollution threatens to spike during this crisis. Environmental justice advocates who work in these communities are not surprised that the hardest hit populations are found in areas that are also overburdened by pollution, poverty, and illnesses such as obesity, diabetes, and cancer, as well as asthma and cardiovascular disease. So, when governors across the country order residents to stay home during the pandemic, these residents are not retreating to safety—they are retreating to toxicity.

Decades ago, sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois zeroed in on how social and environmental conditions led to health disparities betweens black and whites, and he offered solutions that addressed the physical environment. More recently, political scientist Fatemeh Shafiei, director of environmental studies at Spelman College, has studied the social conditions that determine a person’s health outcomes. She found a preponderance of evidence showing that, from cradle to grave, low-income residents and people of color are disproportionately exposed to health-threatening environments in their homes, neighborhoods, and workplaces.

Earlier this month, we heard the US Surgeon General essentially blame the drinking and smoking habits of African Americans and Latinos for contributing to the severity with which they have been hit by COVID-19—even though he noted during the same press conference that it is likely the “burden of social ills” is contributing to the disparities. He was rightly criticized for failing to acknowledge that these disparities are rooted in entrenched structural inequalities that have been in place for centuries and are the product of systemic prejudice. Long after formal segregation was struck down by the courts, for instance, targeted zoning has maintained formerly segregated neighborhoods and put them in the crosshairs of industrial pollution. It’s one of the reasons why today your zip code is still determinative of your life outcome—including your health. Geography is destiny.

COVID-19 is one more chapter in this saga, and we’re seeing that the severity of outcomes is related to a person’s environment. Public health researchers and advocates are concerned that those who live in polluted neighborhoods will fare the worst. It’s why residents are pleading for stronger air pollution regulations in San Bernardino, California, and why residents of Louisiana’s St. James Parish are battling yet another plastics plant. Not only do they not want to heighten their risk of severe coronavirus outcomes, but they also don’t want to see more friends and family diagnosed with cancer. Latinos who live in Houston’s Manchester neighborhood worry that the EPA’s relaxing of environmental enforcement will worsen the already-elevated rates of respiratory illness and asthma among residents. Navajo Nation residents want to access clean water and medical services—and not just during this crisis. As these communities fight for life during the pandemic, they’re also fighting for the right to a safe, clean environment.

King talked of the struggle to help his brethren gain their rightful place in this country, of making “America what it ought to be.” At the heart of that is the right to equal protection under the law, something that Shafiei sees as the end goal of a long history—from slavery to segregation—that has denied these vulnerable communities environmental justice by implementing policies and practices that direct pollution into their neighborhoods.

“People are being denied their equal rights,” said Shafiei. “If you look at the disproportionate number of COVID victims and the percentage of African Americans in the general population—13 percent—then that means it has really impacted their right to live.”

The right to a healthy home is considered by most Americans to be a fundamental part of the American dream, Shafiei writes in a chapter on health disparities in the first American Public Health Association book on healthy homes. But even today more than a third of housing units across the nation—37 million units—contain lead-based paint. Children of color, particularly African American children, have historically been more likely to have elevated blood lead levels, and researchers have found that racial and economic disparities persist today largely due to differences in environmental exposure.

We have waited far too long to address environmental injustices, and generations of Americans have paid the price. Lead exposure is just one example: Local health care agencies wait until children are exposed to lead before intervening, rather than preventing the exposure from happening in the first place. Today we face a similar challenge when it comes to addressing COVID-19 in these communities. This is why U.S. Representatives Raúl M. Grijalva, A. Donald McEachin, and Alan Lowenthal are scheduled to host an upcoming live-streamed roundtable to discuss how the fight for environmental justice can be incorporated into the government’s coronavirus response efforts.

If Americans recognize that these two battles are one in the same—and find the moral courage and political will to fix them—then perhaps environmental justice communities won’t be so hospitable to the ravages of diseases like COVID-19, said Michele Roberts, the national co-coordinator of the Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, which aids grassroots organizations working in communities burdened by toxic chemicals, polluting facilities, and contaminated sites.

“[Vulnerable communities] don’t have access to the protective gear, yet they have access to this virus in disparate forms and they equally have access to toxic pollution in disparate forms,” said Roberts. “Something is wrong with that.”

For Shafiei, collecting more COVID-19 data on race/ethnicity and income is key, in addition to assessing social, economic, and environmental stresses and vulnerabilities. This can help policymakers effectively direct resources to these communities. She points out that one of the obstacles to documenting the health effects of environmental hazards is the delay between exposure and the appearance of disease. With COVID-19, however, we immediately see not only how vulnerability translates into exposure, but we can also see how decades of environmental health disparities have contributed to underlying health conditions.

“COVID showed that it is the result of all these years of policies and practices that have really been detrimental to the health of minority communities and has put them at risk,” said Shafiei, a former member of the EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council from 2012 to 2018. (She also served as an environmental justice consultant for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

As we battle this disease, will we also work to find a solution to the underlying condition that plagues our country? Will we finally tear down the structural inequalities that prevent the Manchesters, the St. James Parishes, and the San Bernardinos from escaping the chokehold of industrial pollution?

In 1968, King didn’t shy away from the challenges that his generation faced. His words ring even truer today: “We have been forced to a point where we are going to have to grapple with the problems that men have been trying to grapple with through history, but the demands didn’t force them to do it. Survival demands that we grapple with them.”

As we shelter in our homes and ask ourselves what comes next, let’s remember what King told the hundreds who gathered that April night in Memphis. He reminded the crowd that they too faced a decision: whether to support the sanitation workers, even though it was not their fight. “Be concerned about your brother,” said King. “You may not be on strike, but either we go up together or we go down together.”

As families continue to lose loved ones to COVID-19 and we determine how best to help those in need, let’s not forget the other crisis that is so closely related to the pandemic’s ravages—the environmental justice crisis. As King said, nothing would be more tragic than to stop now.