President Trump has shifted from glibly promising the end of social distancing by Easter to warn of a “painful two weeks ahead” as the United States now reports more cases of COVID-19 than any other country. As of March 27, most states had implemented some kind of social distancing policies, from shutting down schools and non-essential businesses to imposing stay-at-home orders to slow down the spread of the coronavirus. But did they act too late?

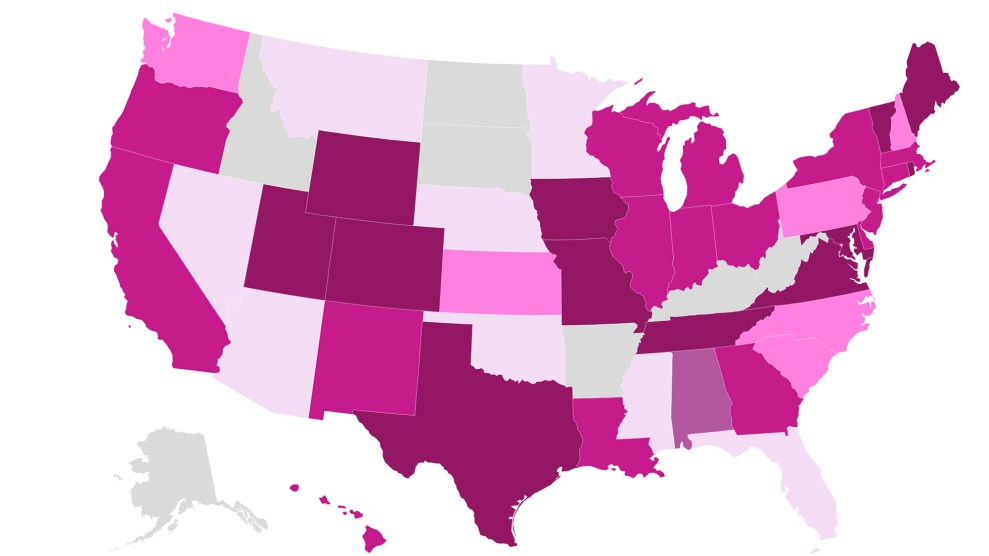

There is already evidence that state-level decisions on when to require social distancing were driven by politics, not public health. By March 16, the governors of all 50 states had declared a state of emergency. Yet as the animation at the top of this article shows, Democratic governors generally declared emergencies before Republican governors. Four of the last five states to declare an emergency (West Virginia, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Georgia) have Republican governors.

That data comes from a study released last week by political scientists at the University of Washington, who found that states with Republican governors and a higher number of Trump voters were slow to roll out policies to control the spread of the virus—potentially undermining efforts to “flatten the curve” of transmission.

The researchers looked at when governors in every state announced five important social distancing measures: closing schools and non-essential businesses, putting restrictions on restaurants and social gatherings, and issuing stay-at-home orders. States started implementing these policies on March 10, nearly two weeks after the first reported date of community transmission of coronavirus in the United States. But some states moved a lot quicker than others.

States’ delays in taking action could produce significant, ongoing harm to public health, the researchers write. The variation in the timing of these policies echoes the 1918 influenza pandemic, when officials were faced with similar decisions whether to require social distancing. Philadelphia held a massive parade to welcome soldiers home while St. Louis cancelled a similar event; it had one eighth the number of deaths as Philadelphia. The University of Washington researchers note the recent contrast between Kentucky and Tennessee’s official responses to the coronavirus: “On 6 March 2020, after Kentucky had its first confirmed case of COVID-19, Governor Andy Beshear (D) immediately called a state of emergency, encouraged social distancing, and closed bars and restaurants ten days later. But when neighboring Tennessee uncovered its first confirmed case of COVID-19 on March 5th, Governor Bill Lee (R) waited until 12 March to declare a state of emergency and finally closed restaurants and bars on 22 March.” As of March 31, Kentucky had 480 reported cases, according to the New York Times; Tennessee had 1,642.

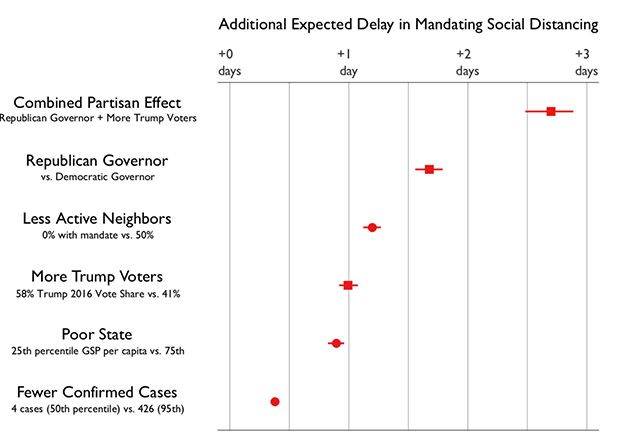

Overall, the researchers found that the strongest predictor of why a state responded slowly to the pandemic was political ideology. States with Republican governors and a higher percentage of Trump supporters were the slowest in implementing social distancing policies. “All else equal, states with Republican governors and Republican electorates delayed each social distancing measure by an average of 2.70 days… [A] far larger effect than any other factor, including state income per capita, the percentage of neighboring states with mandates, or even confirmed cases in each state,” they write.

The researchers hypothesize that these states waited to act partly because of President Trump’s statements downplaying the virus’s severity, which were magnified by Fox News and other conservative media in the early stages of the pandemic. They also speculate that Republican governors may have feared retaliation if they were seen to contradict the president.

The researchers also looked at various factors that may have influenced a governors’ decision to delay mandating social distancing, including the number of coronavirus cases in the state, what neighboring states were doing, and their states’ economic status. They found that the number of cases had little bearing on when policies were introduced, but neighboring states’ policies did influence each other. Poorer states were slower to adopt social distancing.

“Barring positive developments in the fight against COVID-19, the public health impact of this delay is likely to be massive,” the researchers conclude. “In a state where coronavirus infections are doubling every seven days, this would raise the peak caseload by 30.6%. In a state where infections are doubling every three days, Republican partisanship might raise the peak level of cases by 86.6%.”

Correction: An earlier version of the animated map used the wrong colors for Nebraska and Nevada.