Inmates at the Cummins Unit prison in Arkansas wait to be admitted through a gate in 2009 Danny Johnston/AP

Over the weekend, a man incarcerated at Cummins Unit prison, an Arkansas state prison in Grady, tested positive for COVID-19, becoming the first prisoner in the state correctional system there to do so. The corrections department responded by quickly testing all the other men housed in the same barracks—mass testing that most other states have not done in their prisons.

The results, made public on Monday, were shocking: The state corrections department announced that a whopping 43 of the 46 other men in the housing unit had tested positive. They were all asymptomatic and are now quarantined.

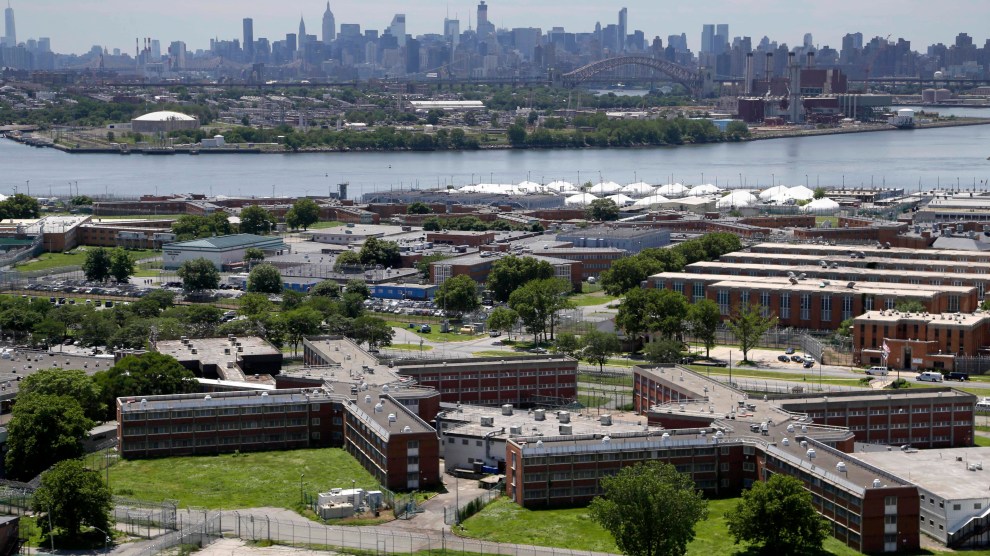

Health experts around the country have warned for weeks that once the virus gets into crowded jails and prisons, it could spread much faster than it does in the general population. Rikers Island jail complex in New York City and the Cook County Jail in Chicago are already experiencing massive outbreaks, with hundreds of inmates testing positive; the federal prison system has seen at least 352 prisoners test positive nationwide.

But most facilities—in the federal prison system, and in state prisons and local jails—aren’t conducting or don’t have access to the kind of mass, quick testing that Arkansas did, so it’s impossible to know how bad the outbreaks really are. “We have very, very limited amounts of the testing kits,” says Brandy Moore, secretary treasurer of the national union that represents correctional officers in federal prisons. At a federal prison complex in Terre Haute, Indiana, “we have between 2,500 and 3,000 inmates, and we were given four tests,” Steve Markle, another leader of the national union who works at the prison, told me in late March. At the federal prison in Oakdale, Louisiana, where at least six inmates have died from the disease and dozens have tested positive, correctional officers were told to stop testing people and just assume that anyone with symptoms had been infected, according to Ronald Morris, president of the local union there—even though, as proven in Arkansas, plenty of people can be asymptomatic.

All this is to say that statistics reported by the Federal Bureau of Prisons are likely massive undercounts. “Our numbers are not going to be adequate because we’re not truly testing them,” says Moore.

At Chicago’s Cook County Jail, at least, a lawsuit is hoping to improve the situation. After a suit, filed earlier this month, alleged that “little or no preventative testing is being done to identify and remove sick detainees,” a judge on Thursday ordered the sheriff to develop a policy for testing inmates with symptoms. But again, that would still miss all the potentially infected but asymptomatic inmates. (The Cook County Sheriff’s Office says it had already been testing inmates since late March who showed symptoms, and that it is now working with hospital staff to accelerate testing to slow the spread of the virus.)

The Arkansas Department of Corrections was able to test everyone in the barracks at Cummins Unit prison because it received 250 testing kits from the state health department, according to corrections spokesperson Dina Tyler. In contrast to many prisons and jails around the country, she says, all inmates in the Cummins Unit facility are also each equipped with two masks, which they have manufactured themselves. The corrections department is working to get tens of thousands of masks to other inmates around the state. “Health official after health official has talked about how infectious this virus is, and how easily it’s transmitted,” she says of the precautions the corrections department has taken.

This article has been updated with clarification from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office about its testing protocols.