Jaap Arriens/Zuma

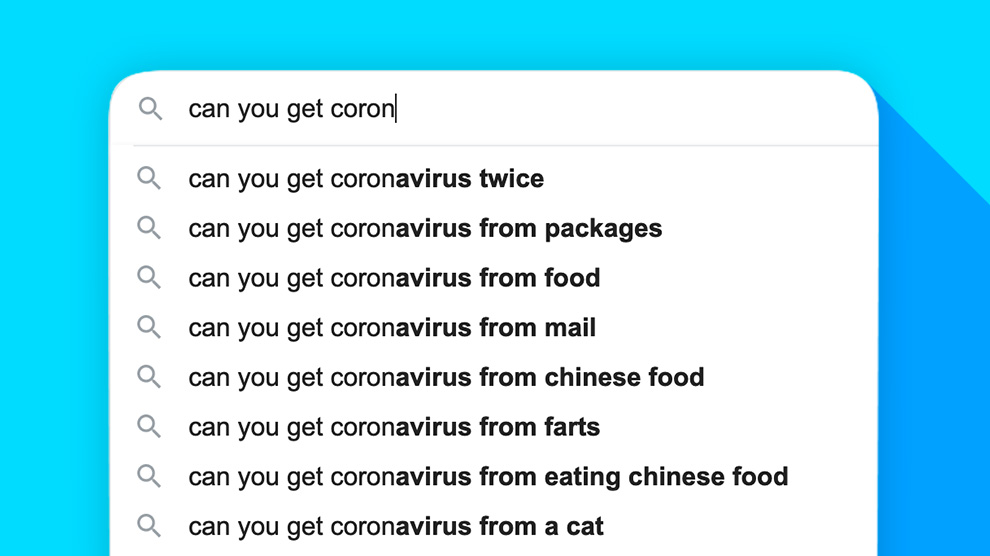

There’s a pandemic sweeping the globe that has already infected more than 2 million people and killed nearly 140,000. Three out of four people on Earth are under some form of lockdown in order to curb the spread of COVID-19, the illness caused by a novel coronavirus that first emerged last December in China. While epidemiologists, data scientists, and other public health experts struggle to understand the new virus and inform the public, another epidemic is spreading quickly: White guys on social media who suddenly have become infectious disease experts.

How many people will get sick? When will we be able to go out again? A vaccine is going to take how long? These are just a sampling of the questions we hope the specialists will answer. But that guy you went to high school with who has no relevant knowledge much less graduate degrees thinks you should listen to him instead.

Sure, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has been doing this for 36 years, but that guy you vaguely know from summer camp just doesn’t think Fauci understands the disease like he does. “When this is all over, the country will know that Dr. Anthony Fauci was the anti-hero,” a Twitter user who self-identified as a retired math teacher but neglected to mention he doesn’t understand the meaning of “anti-hero” tweeted. “So wrong on number of deaths. Not one bit concerned about Americans and their loss of jobs.”

This outbreak of ill-placed expertise is not unique to the pandemic. In fact, the phenomenon of people with little knowledge acting as if they should be listened to has been studied and has some robust research behind it. They are all living, tweeting, opining, over-sharing examples of the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias described back in 1999 by social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger that explains why people overestimate their knowledge and abilities. A fine example is the president of the United States, who bragged about having an uncle who attended MIT and claimed that doctors kept asking him why he understood so much about the novel disease. “Maybe I have a natural ability,” President Donald Trump told reporters during a press conference at the CDC. “Maybe I should have done that instead of running for President.”

This combination of arrogance and stupidity also has been rampant among the armchair epidemiologists who have now emerged. Alex Berenson, former New York Times reporter turned right-wing media darling, said on Fox News that no one under 30 years old is at “serious risk” of this virus. That is simply not true.

Mark Humphries, an Australian comedian, captured what is going on perfectly in a video he tweeted on the topic. “My name is Dougall Merton and I’m a certified armchair epidemiologist. I graduated from the University of Wikipedia,” he says in the hilarious but painfully accurate satirical video. “It was only after a few days after graduation that I published my first peer-reviewed text message to friends and family.”

The Armchair Epidemiologist pic.twitter.com/t4CvJo3KCL

— Mark Humphries (@markhumphries) April 9, 2020

The armchair epidemiologist is everywhere and spans across age, race, and political leanings, but skews white and male. Because I’m extremely privileged to be healthy and safe at home, and because I’m a glutton for punishment, I mindlessly scroll through Facebook a few times a day.

One day, a friend of mine had posted an article warning about the dangers of misinformation during a public health crisis. Listen to the experts who want you to wash your hands and not your uncle’s wife who thinks the virus is caused by 5G cell phone towers. Simple, right? The first comment was from a man. “I think even the experts are misinformed.” Stunning! The World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institute for Health, all got it wrong. But thank God, Chad from homeroom in 2005 has got a handle on the crisis.

Who are you going to listen to? The epidemiologists and data scientists or the guy who sat behind you in homeroom 15 years ago?

— Nathalie Baptiste (@nhbaptiste) April 9, 2020

Soon the self-proclaimed experts started appearing up and down my feed. Another man commented on a different article about the science behind the models that try to figure out how many people will die from the virus. “I’m no medical expert,” he began, at which point he should have stopped. If you are not a medical expert, why are you offering your opinion on a medical topic? He did, of course, and went on to explain how long he thought it would be before infection rates would finally begin to slow.

And it’s not just Facebook. I’ve seen long Twitter threads opining about important aspects of the virus only to click on the user’s profile to find out it’s just some guy frustrated at home who, instead of taking care of his children, is just tweeting his hunches. The armchair experts are also posting screeds on Medium.com calling the virus a hoax or media-created hysteria. An infamous one by Silicon Valley technologist Aaron Ginn titled “Evidence Over hysteria—COVID-19” received millions of views before it was removed and reposted to a right-wing site. (With the death toll in the US quickly approaching 30,000, I’m sure their posts have aged quite nicely.) Even journalism outlets, who should just be telling the public what the experts are saying, have been guilty of this.

Before you start writing that hate e-mail that I will most definitely laugh at and then delete, I’m not singling out men unfairly; there’s some science—remember that?— to back me up. In the academic world, experts must cite their claims while writing a research paper. And, if you’re writing about an obscure topic with few experts, it’s not uncommon to cite yourself. In essence, you can be your own expert. In 2016, Molly King, a sociologist at Santa Clara University and several other researchers examined 1.5 million research papers between 1779 and 2011 and found that men cited themselves 56 percent more often than did women. In the last 20 years of their data, men cited themselves 70 percent more often than women cited themselves. King and the other researchers explain the wide gap in academic self-citations plainly: Men often tend to have inflated opinions of themselves and often face little backlash for overconfidence.

In fairness to the men in our social media feeds, the federal government’s utter failure in crafting a clear and effective response, crucial weeks spent dithering and denying, President Trump’s refusal to behave with clarity, consistency, or constructive leadership, and the states’ patchwork response, have left people without an essential, credible source of direction and information. So, it’s understandable that everyone across the country is trying to figure what we’re supposed to be doing, and what the end game looks like. But that’s where the public health experts come in. Not the random guy you forgot to unfriend a decade ago.