Mint Images via Zuma

Last month, a city council meeting in Lake Worth Beach, Florida, went viral after an angry city commissioner began shouting at the mayor about the city’s lack of preparedness for the novel coronavirus pandemic that was just beginning to hit the state. “We cut off people’s utilities this week and made them pay what could have been their last check—to us—to turn their lights on in a global health pandemic,” city commissioner Omari Hardy said during the heated argument, which was captured in a two-minute video.

Eventually, Mayor Pam Triolo ended the discussion and the meeting by walking away, and the city of 38,000, which controls its own utilities, issued refunds to those whose electricity had been shut off. This contentious meeting may seem like an unusual event, but the situation Hardy described is becoming more common across the country, where the large number of chronically energy insecure people are now joined by the unprecedented ranks of the newly unemployed. Because utility companies vary from state to state, sometimes from locality to locality, there is no comprehensive approach to addressing what advocates fear could soon exacerbate the health effects of the already deadly epidemic.

“It’s really shameful these are not considered human rights,” Jean Su, the director of the Energy Justice Program at the Center for Biological Diversity says. Energy insecurity—which disproportionately affects communities of color, rural neighborhoods, and the elderly—is defined by a household’s inability to meet their electricity or gas needs, whether from not being able to afford bills, or keeping a home at an unsafe temperature in order to to pay them.

It’s a widespread problem that has not attracted much attention until now. Even though none of the coronavirus relief packages have addressed the issue, at the end of March, eight senators led by Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) introduced a resolution that would ensure that no household would lose electricity or natural gas during the crisis, and that reasonable efforts would be made to reconnect those who had lost service. The method of shutting off services varies widely, from the ability to do it remotely from a computer to sending a service worker to physically flip a switch. The lawmakers also proposed that late fees and other penalties be waived for the duration of the crisis. But the measure gained no traction. Still, advocates say, Congress must act immediately, or the pandemic will likely create even more energy insecure households, and that could add to the number of people who get ill.

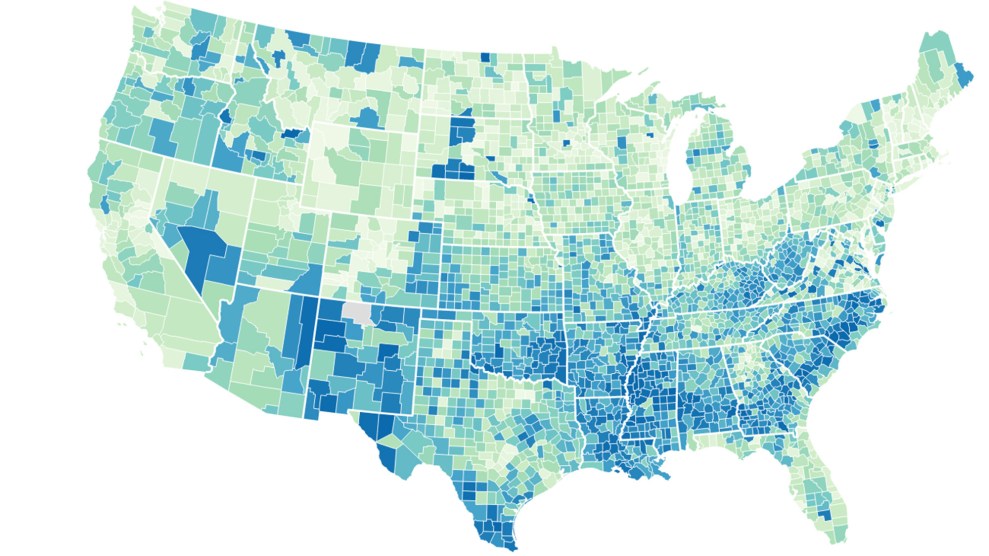

According to a 2015 Energy Information Administration survey, 1 in 3 households in the United States were energy insecure, meaning they struggled to regularly pay their electricity bill. Approximately 20 percent of households had to forgo food or medicine in order to pay an energy bill, 14 percent said they had received a disconnection notice, and 11 percent said they’d kept their home at an unhealthy temperature in order to reduce their energy bills.

The new coronavirus has officially infected nearly 460,000 people in the United States and has killed over 16,000. The true human toll remains unknown, however, because of a testing shortage and misattributions at death. In an effort to slow down the spread of the virus, wide swaths of the economy have been shut down leading to historic job losses and an economic collapse not seen since the Great Depression. In the last three weeks, 16 million people filed jobless claims. “When the economy was doing much better, 37 million households experienced energy insecurity,” Diana Hernandez, a public health professor at Columbia University, says. “Now, that number is definitely going to go up.”

As temperatures rise in the coming weeks, energy insecure households must worry about keeping their homes at reasonable temperatures. Heat can exacerbate the type of preexisting conditions—like chronic lung disease and other respiratory illnesses—that make people more susceptible to severe illness from COVID-19. “The consequences are mental, physical, and they’re fatal,” Hernandez explains. In 2018, a 72-year-old Arizona woman died after her utility service cut her electricity off when it was more than 100 degrees outside. That same year a 68-year-old woman died in New Jersey after her power company cut her service over unpaid bills.

For those experiencing poverty, deciding how to spend money is a constant battle among the basic needs of food, shelter, health, and utilities. A problem made devastatingly acute by the pandemic. “Are you going to try to get medication because you got coronavirus or pay utilities?” Su asks. “It’s just these impossible choices that people have to make.”

Absent a federal response, protection from utility shut-offs is being carried out state-by-state. Seventy-two percent of energy utility companies are private, while the remaining are publicly-owned or managed by non-profit membership-run cooperatives. Many states and other local governments have imposed moratoria on power and gas companies turning off utilities during the pandemic, and some private companies have also voluntarily suspended shut offs. “The quality of the moratoria vary widely,” Su explains. “And some of them are not good enough.” For example, as HuffPost reported earlier this month, North Carolina ordered the state utilities to halt shut-offs, but a rural electric co-op, which doesn’t fall under the same jurisdiction, did not have to follow the state’s orders. The result was that many households had their power cut off in the middle of a global pandemic.

Another utility service that has come into the spotlight is water. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has advised that frequent hand-washing with warm water and soap is one of the most effective ways to kill the virus. But for the 14 million households who struggle to pay their water bills and are subject to shut offs, it’s not an easy task. Like with energy utilities, states have issued separate moratoriums on water shut-offs during the practice, while advocates call for Congress to act.

Advocates believe the freezes may be the right approach but don’t go far enough; pausing utility payments will only mean that the bill will come due eventually. “By the end of this crisis, you’re going to be crippled by debt,” Su says about low-income households. Advocates urge using this crisis as an opportunity to find different ways to end the problem of energy insecurity once and for all by guaranteeing basic utility services to everyone. This pandemic has exposed many of the failures of the current system, Hernandez says, adding, “Maybe now there’s room for the idea that we don’t need to shut off [utilities] at all.” Su believes it’s time for a revamp of the entire system as well. “We need to rethink how our entire utility services systems work,” she says. “They need to be guaranteed human rights.”