A capped oil well ready to start pumping near Jal, New Mexico. Roberto E. Rosales/Zuma

This piece was originally published in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

Long before New Mexico or Wyoming identified any cases of COVID-19, even before residents began hoarding eggs and sacks of flour, state budgets were feeling the impact of the disease.

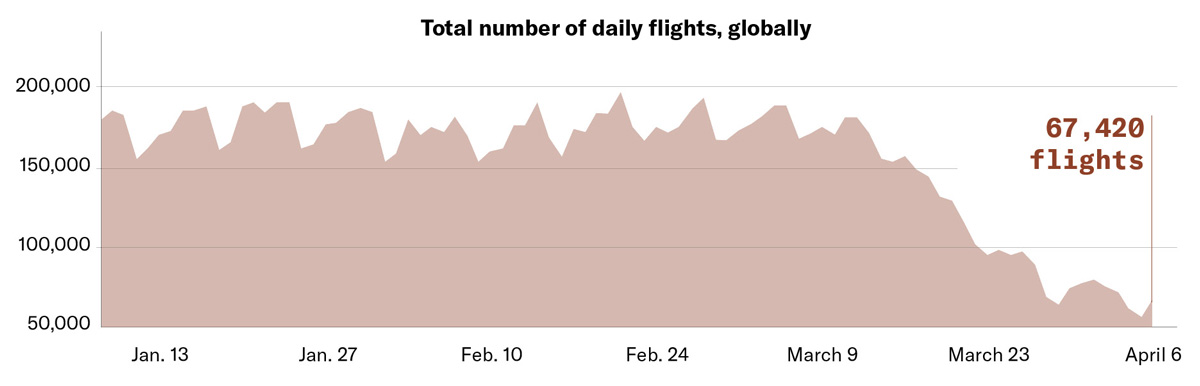

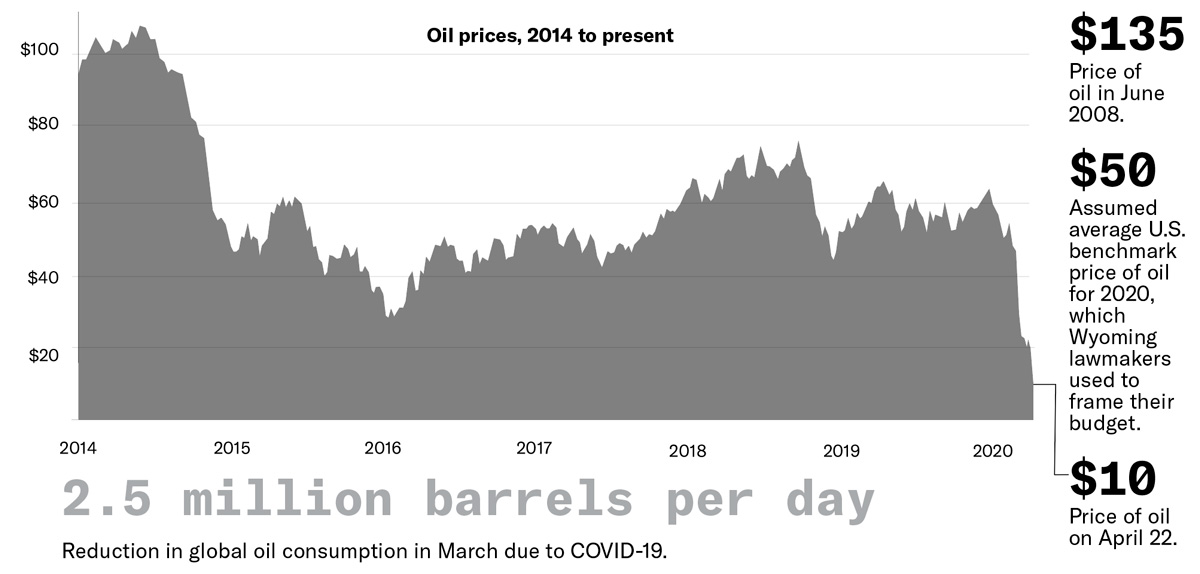

In mid-January, when the epidemic was still mostly confined to China, officials there put huge cities on lockdown in order to stem the spread. Hundreds of flights into and out of the nation were canceled, and urban streets stood empty of cars. China’s burgeoning thirst for oil diminished, sending global crude prices into a downward spiral.

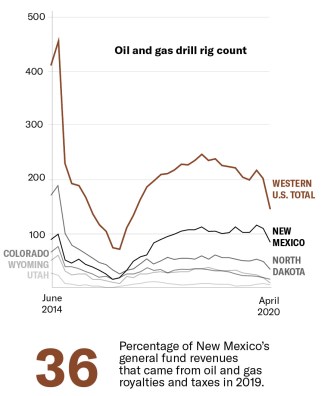

And when oil prices fall, it hurts states like New Mexico, which relies on oil and gas royalties and taxes for more than one-third of its general fund. “An unexpected drop in oil prices would send the state’s energy revenues into a tailspin,” New Mexico’s Legislative Finance Committee warned last August. Even the committee’s worst-case scenario, however, didn’t look this bad. Now, with COVID-19 spanning the globe, every sector of the economy is feeling the pain—with the exception, perhaps, of toilet paper manufacturers and bean farmers. But energy-dependent states and communities will be among the hardest hit.

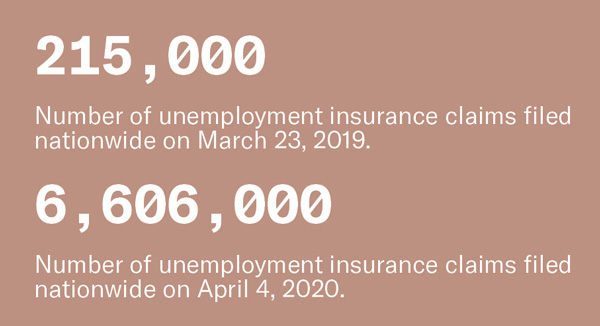

At the end of December, the US benchmark price for a barrel of oil was $62. By mid-March, as folks worldwide stopped flying and driving, it had dipped to around $20, before falling into negative territory, and then leveling off around $10 in April. The drilling rigs—and the abundant jobs that once came with them—are disappearing; major oil companies are announcing deep cuts in drilling and capital expenditures for the rest of the year, and smaller, debt-saddled companies will be driven into the ground.

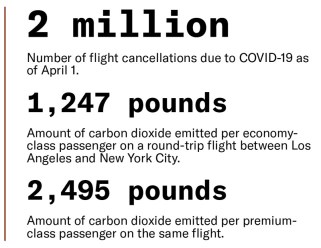

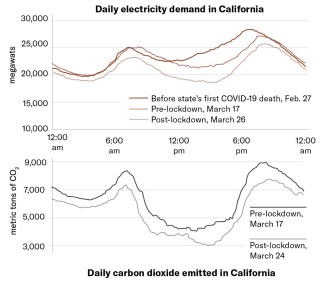

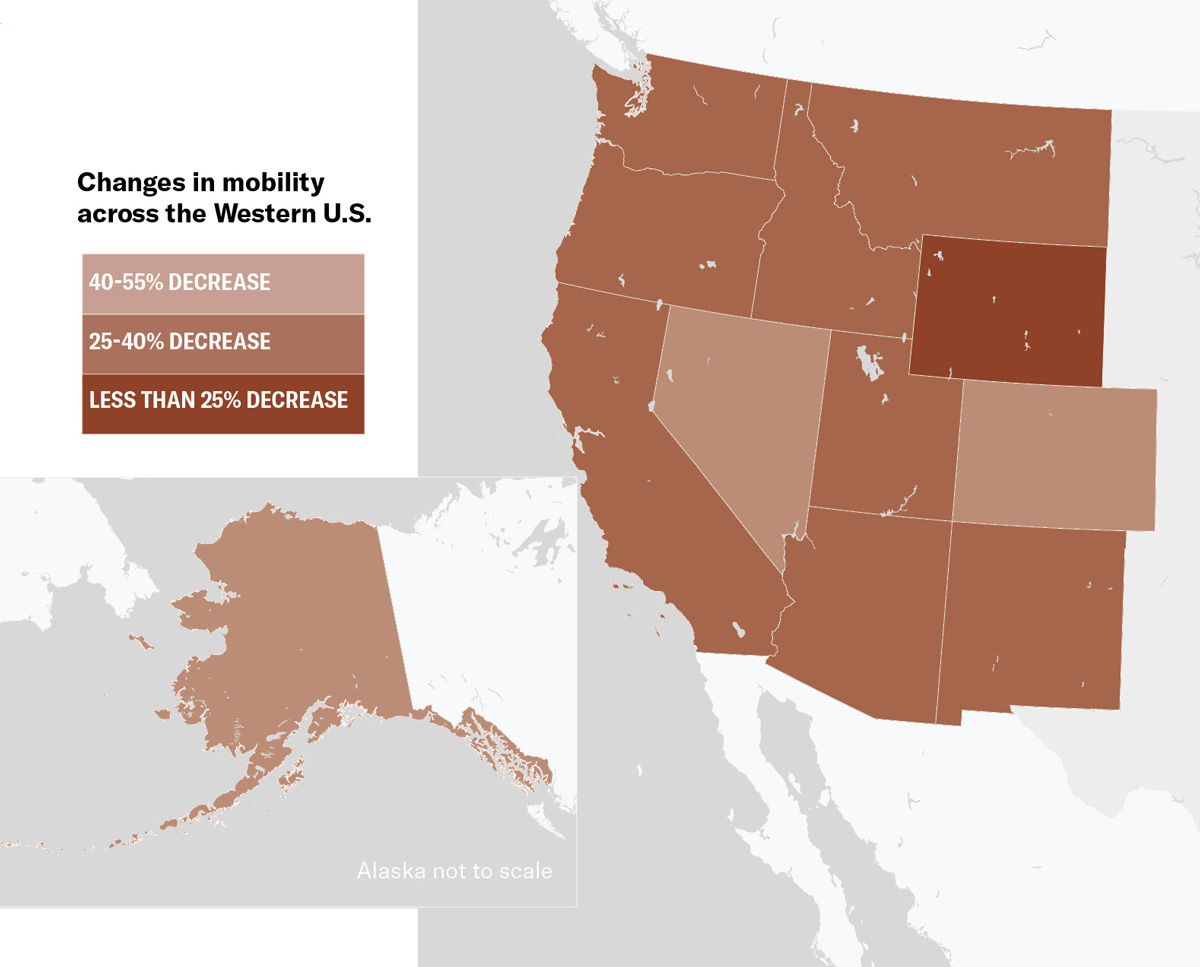

COVID-19 and related shocks to the economy are reverberating through the energy world in other ways. Shelter-in-place orders and the rise in people working from home have changed the way Americans consume electricity: Demand decreased nationwide by 10 percent in March. As airlines ground flights, demand for jet fuel wanes. And people just aren’t driving that much, despite falling gasoline prices, now that they have orders to stay home and few places to go to, anyway.

The slowdown will bring a few temporary benefits: The reduction in drilling will give landscapes and wildlife a rest and result in lower methane emissions. In Los Angeles, the ebb in traffic has already brought significantly cleaner air. And the continued decline in burning coal for electricity has reduced emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

The slowdown will bring a few temporary benefits: The reduction in drilling will give landscapes and wildlife a rest and result in lower methane emissions. In Los Angeles, the ebb in traffic has already brought significantly cleaner air. And the continued decline in burning coal for electricity has reduced emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

But the long-term environmental implications may not be so rosy. In the wake of recession, governments typically try to jumpstart the economy with stimulus packages to corporations, economic incentives for oil companies, and regulatory rollbacks to spur consumption and production. The low interest rates and other fiscal policies that followed the last global financial crisis helped drive the energy boom of the decade that followed. And the Trump administration has not held back in its giveaways to industry. The Environmental Protection Agency is already using the outbreak as an excuse to ease environmental regulations and enforcement, and even with all the nation’s restrictions, the Interior Department continues to issue new oil and gas leases at rock-bottom prices.