Philanthropist and ex–New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg reacts to a joke at his expense at a 2014 charity gala.AP Photo/John Minchillo

If you’re one of the 10 percent of Americans who works for a nonprofit, you’re biting your nails right now. A CNN commentator recently called COVID-19 an “extinction-level event for America’s nonprofits.” Philanthropy News Digest reports that 83 percent of nonprofits have seen a drop in revenue between March and June 2020. Seventy-one percent say they can’t provide the same services they once did. The number of nonprofit staff dropped by almost half amid a torrent of layoffs and pay cuts. And philanthropic grants are down by a third. No wonder, right? Who has loose change to give away at a time like this?

Billionaires do.

The biggest philanthropists, the ultra-rich, are doing great. Between March 18 and June 5, American billionaires added more than half a trillion dollars to their collective net worth. Thanks to growing inequality, small-dollar donations to charity are being replaced by upper-class philanthropy. But upper-class philanthropy is a lot less likely to make its way to people in need.

Those are the conclusions of a new report from the Institute for Policy Studies, a DC-based progressive think tank that backs an overhaul of charity laws. The number of donors is falling—by 12 percent from 2009 to 2019, the report finds, likely because stagnant wages and growing inequality have made it difficult for many small donors to keep giving. In 1989, 81 cents of every dollar that went to charity came from an individual. In 2019, that figure was 69 percent. On paper, the richest Americans have made up for a drop in middle- and working-class donations. In practice, their donations are more likely to gather dust—and tax deductions.

Where small donors have traditionally given to working nonprofits, wealthy donors prefer donor-advised funds and foundations. (Donor-advised funds, increasingly popular with investors, let you donate, collect a tax deduction for the full value, and decide what to do with the money later. The Chronicle of Philanthropy calls them a “personal charitable savings account.”) That money—even when it comes in large amounts, or “mega-gifts”—doesn’t always trickle down to the grassroots organizations it’s supposed to help. In fact, most charitable foundations don’t have to spend more than 5 percent of their funds per year. Whether or not they give to working nonprofits, they’re still able to shield donors from the IRS by allowing billionaires to write off their contributions as tax deductions.

The UC Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman has called mega-gifts the equivalent of a “tiny, tiny wealth tax.” The top 20 US billionaires after Bill Gates and Warren Buffet, Zucman writes, donated about 0.3 percent of their wealth in 2018. The catch: It’s barely more than the taxes they’d owe on half their wealth, even under our billionaire-friendly tax code. More than 200 ultra-rich donors have picked up great press for the Giving Pledge, a Gates/Buffet-led initiative to give away most of their assets. But as IPS points out, if the US signers gave away half of their net worth—$485 billion, including to their own foundations—they’d be shorting Americans $360 billion in taxes, given that they’re able to write off so much of their contributions. Unfortunately, donations to museums, universities, and even public health programs can’t replace the essential function of taxes: to float social goods like working transit, housing subsidies, unemployment insurance, and public education.

If you see an uncanny echo of dark money in politics, you’re not wrong. When small, individual donors get squeezed out, the report says, charities have to start responding to what a few big donors want. IPS calls it “mission distortion.” Despite bringing in massive tax breaks, much of the almost $16 billion donated by the top 50 philanthropists in 2019 “may not actually get into the hands of active public charities for years—or ever, potentially, in the case of donor-advised funds.” Even when mega-gifts do go to active working charities, the report notes, “they tend to be directed toward larger organizations, and towards causes that the wealthy prefer.” The most popular targets for those mega-gifts were the donors’ own private foundations.

Many private foundations are deeply entwined with offshore trusts and tax havens: Illinois governor and billionaire Hyatt heir J.B. Pritzker squirreled significant shares of his estimated $3.5 billion net worth into a tangle of Carribean trusts and holding companies, all of which funnel cash into his private foundation. (Other members of the Pritzker family have donated to Mother Jones.) America’s richest family, the Waltons, runs a foundation that sits on nearly $5 billion in assets. And “99 percent of the Foundation’s contributions since 2008,” one Forbes contributor reports, were made through trusts “specifically designed to help ultra-wealthy families avoid estate and gift taxes.”

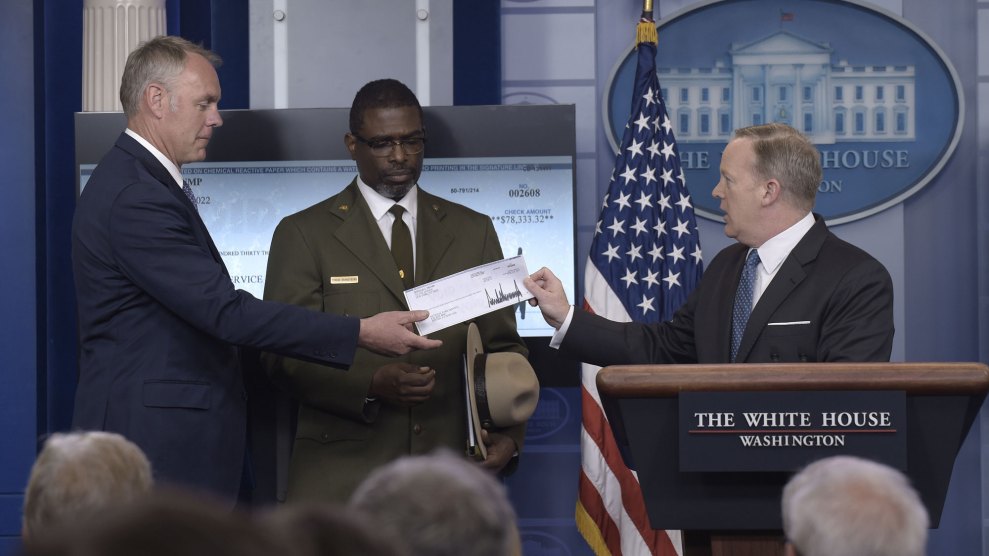

And some foundations could use way more oversight. The Trump Foundation dissolved in 2018 after a complaint from New York’s attorney general accused it of a “shocking pattern of illegality,” including collusion with the Trump campaign, calling it “little more than a checkbook” for Trump’s “business and political interests.” The opioid–rich Sackler family—some of whom own Purdue Pharma, which has come under increasing scrutiny for aggressively hawking OxyContin—has lent its name to the Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation, the Sackler Trust, the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Foundation, La Fondation Sackler, and the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation—among others.

The Sackler and Walton names, among others, are splashed across institutions, from art galleries to hospitals and universities (although many museums, along with Tufts University, have now stripped references to the Sacklers from their buildings). That doesn’t always bode well for small charities. From the report:

Top-heavy philanthropy favors bigger charities that already have sophisticated major donor programs, the capacity to manage and implement gifts of enormous size, as well as the infrastructure to accommodate gifts of appreciated stock and high-value noncash assets. This may put smaller, more independent, and potentially more innovative and nimble organizations at a disadvantage.

In other words, high-dollar philanthropy more often looks like equity billionaire David Booth’s $300 million gift to the already-very-rich University of Chicago’s business school—now the Booth School of Business—rather than a big check for scrappy youth organizations, prison abolitionists or hyper-local environmental justice groups like those backed by Resist, a nonprofit that makes modest grants to grassroots organizers. From 2017 to 2018, the Chronicle of Philanthropy found that giving to the 100 biggest charities grew 11 percent, even as giving fell overall. Nonprofit Quarterly says we live in an age of “philanthropic plutocracy.” And since 1985, according to Berkeley’s Zucman, foundation wealth has grown by more than half as a share of household income. Foundations now hold more than $1 trillion in assets, he writes.

Charity rules, drawn up in 1917 to benefit the Gilded Age rich, worked best in the postwar years, when millions more Americans had cash to throw around—which they did, consistently, at a rate of around 2 percent of their incomes. But when those incomes stagnated, charities leaned more and more on Walmart heirs parking billions in family foundations and dodging capital gains while they vote with their wallets. Are we really better off for that?