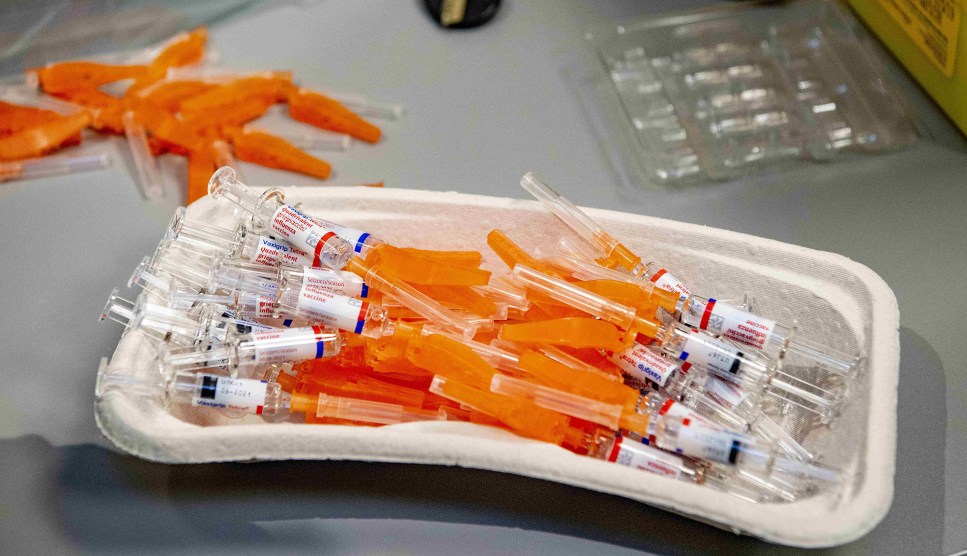

A healthcare worker administers a shot.Inna Borodaieva/Zuma

On Monday, the race among pharmaceutical companies to complete a vaccine effective against COVID-19 reached a critical new stage. Pharmaceutical company Pfizer and German-based biotechnology firm BioNTech announced that their joint vaccine appeared to be more than 90 percent effective in test trials, a result that surpassed earlier disclaimers from researchers that a potential coronavirus vaccine might be only 60 percent effective.

If the vaccine continues to show promise, Pfizer anticipates that by the end of the year, it could produce 50 million doses, enough for 25 million recipients to receive the two-dose protocol—ramping up to more than 1.3 billion in 2021. “This is a historical moment,” Kathrin Jansen, head of vaccine research and development at Pfizer, told the New York Times. “This was a devastating situation, a pandemic, and we have embarked on a path and a goal that nobody ever has achieved—to come up with a vaccine within a year.”

What’s more, Pfizer is not alone. One drug company, Moderna, is deploying the same novel messenger-RNA technology as did Pfizer and BioNTech. Other vaccine candidates rely on a manmade virus rather than mRNA to instruct the body to target the coronavirus.

If Pfizer’s production plan continues and meets the standards laid out by the Food and Drug Administration, “vaccinations might start in the second week of December,” says John Grabenstein, vice president of the American Pharmacists Association and former head of US Department of Defense military immunization program. The speed with which Pfizer and BioNTech have developed the vaccine is unprecedented, and there remain a number of steps the company must go through to prove its safety and efficacy—both globally and in the US—before it’s made available to the public. Grabenstein says a vaccine before 2021 is only realistic “if several assumptions all come to pass,” including speeding through regulatory hoops and efficient scaling up of drug into the hundreds of millions of doses.

The FDA has indicated that it wants two full months of safety data on the volunteers who have received Pfizer’s vaccine. Originally there were supposed to be 30,000 subjects but later that number was increased to more than 40,000—38,955 of whom have taken both of the vaccine’s two doses—though, as with most research protocols, half of the vaccine doses are placebos. (Pfizer says it will continue to monitor its volunteers for a total of two years.) Initially, Pfizer wanted to wait until 32 of its subjects contracted COVID-19, then see how many of them had received the real vaccine; the larger the percentage of infected volunteers in the placebo group, the more effective the vaccine appeared to be. At that point, Pfizer would start submitting data to the federal government, continuing its tracking until 164 volunteers tested positive. To have a more robust data set, the company ultimately agreed to wait until it had 96 infected volunteers, rather than 32. The drug company will still track positive subjects until it reaches 164 for this section of its data collection.

When announcing the efficacy of its vaccine, the company said it plans to submit that safety data, along with an application for an emergency use authorization—which fast tracks the drug and makes it temporarily available—by the third week of November.

Once Pfizer and BioNTech submit that safety data, “FDA has to read it, FDA has to convene an advisory committee, CDC reads it, CDC convenes an advisory committee,” Grabenstein says, a process that could take several more months. The HPV vaccine, for example, was tested for almost a decade before it entered the market. Scott Gottlieb, a former Trump administration FDA commissioner who sits on Pfizer’s board told the Washington Post that even if the vaccine is approved before the end of 2020, that the general public would not have access until summer or autumn of next year. Plus, the FDA won’t just be appraising the trial data, but also Pfizer’s capacity to actually manufacture the vaccine. “Manufacturing glitches come up all the time,” Grabenstein says. “Usually behind the scenes, and nobody notices.”

Manufacturing hurdles are one thing, but distribution is another. Pfizer’s vaccine candidate must be stored at ultra cold temperatures, negative 80 degrees Celsius, according to the New York Times. If it ends up being the primary tool used to immunize the population from the disease, there is the crucia question of transportation. “There’s no getting around it. These have stark temperature demands that will constrain access and delivery,” J. Stephen Morrison, senior vice president of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the Times in September.

To put to rest public concerns that the vaccine has been produced dangerously quickly—more than 60 percent of Americans recently polled are concerned the vaccine will be approved along political, not scientific, lines—Pfizer is adding additional endpoints to its analysis, including instances where data is collected to determine the drug’s effects. “The final analysis now will include, with the approval of the FDA, new secondary endpoints evaluating efficacy based on cases accruing 14 days after the second dose as well,” Pfizer’s press release noted. “These secondary endpoints will help align data across all COVID-19 vaccine studies and allow for cross-trial learnings and comparisons between these novel vaccine platforms.”

In large part, the public mistrust surrounding the vaccine is a combination of an increasingly strong anti-vaxx movement on the extremes of the left and the right political spectrum, and another serious consequence of the Trump administration’s pandemic strategy of downplaying the disease, making unrealistic promises on solutions, discrediting science, and publicly chastising health officials who urge caution in the face of those unrealistic expectations. “I think the US government has not been communicating enough with the public in a way that is reassuring,” Grabenstein says.

On Monday morning, as news of the potential vaccine hit Twitter, Mike Pence chalked up the progress to Pfizer’s participation in Operation Warp Speed—the government’s vaccine development partnership.

As Pence claims credit, Pfizer says it did NOT join in the administration's partnership.

Pfizer head of vaccine development Dr. Kathrin Jansen told the NY Times: “We were never part of the Warp Speed … We have never taken any money from the U.S. government, or from anyone.” https://t.co/GScL3vodx9

— Geoff Bennett (@GeoffRBennett) November 9, 2020

Pfizer is not a member of Operation Warp Speed. In fact, the drug company struck an almost $2 billion deal in July with the federal government to produce 100 million vaccine doses, but not to develop the vaccine itself. In September, Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla explained his reasoning on NBC’s Face the Nation. “When you get money from someone that always comes with strings,” he told host Margaret Brennan. “They want to see how we are going to progress, what type of moves you are going to do. They want reports. I didn’t want to have any of that…I wanted to keep Pfizer out of politics, by the way.”

But politics were inevitable. Shortly after the Pfizer’s announced its findings and the vice president tried to grab credit for the administration, Trump tried a different approach: Claim the timing of the announcement was delayed to thwart him.

The @US_FDA and the Democrats didn’t want to have me get a Vaccine WIN, prior to the election, so instead it came out five days later – As I’ve said all along!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 10, 2020

It’s true that if Pfizer had stuck with its original plan to submit its findings to the FDA after only 32 subjects tested positive for the disease, the study would likely have wrapped up last month. But with its decision to wait until Monday, when it had 96 cases to submit, Pfizer’s trial stands on more robust ground, statistically speaking.

As Pfizer continues to turn its findings over to the FDA for the eventual emergency-use authorization, allaying the suspicions of the large number of Americans who are concerned with of how the vaccine was created becomes the next big challenge. A September poll by Kaiser Family Foundation found that only two thirds of respondents indicated they trusted FDA’s sister agency, the CDC—a 17 percent drop from April. The same poll showed that less than half of Americans would take a vaccine available before the election. And though that’s no longer a concern, there’s still trust to regain. Not to mention, the monumental effort necessary to distribute a treatment capable of addressing a worldwide pandemic. “There’s a real disconnect between vaccine producers and the headlines that come out about a vaccine approved by Christmas,” Emma Hodcroft, a molecular epidemiologist at University of Bern in Switzerland, told the Wall Street Journal on Tuesday. “A little bit more realism about the time frame for vaccinating the population would be helpful.”