Bruce Jackson got into photography as a means to an end. Working as an ethnographer studying African American work songs in Texas prisons, Jackson started taking photos for reference. While doing this work in the late ’60s, he met Terrell Don Hutto, assistant warden of the Ramsey Prison Farm in 1967. In 1971, Hutto was named commissioner of the Arkansas Department of Corrections. He later cofounded the Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic), America’s first private, for-profit prison company. Today, a detention center in Texas named after Hutto holds immigrant families.

Jackson’s connection to Hutto allowed him access to prisons in Texas and Arkansas, including the 16,000-acre Cummins Farm Unit, where Hutto lived in Arkansas. Jackson initially went to Cummins to see how Hutto was reforming the state prison system, which had been put under federal supervision after a judge described it as “a dark and evil world” that violated prisoners’ constitutional rights. (An incident in which bodies were found buried on the Cummins grounds was later depicted in the 1980 Robert Redford film, Brubaker.)

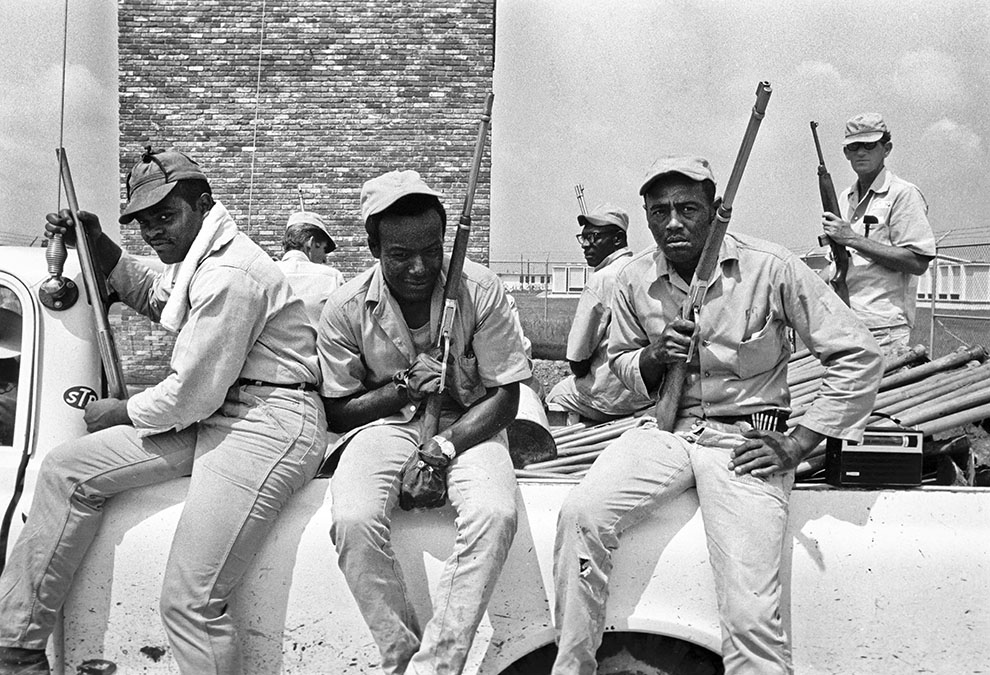

One of Hutto’s tasks was to end the use of armed inmates as guards, a practice that had also been common in Texas prisons. In his book Inside the Wire: Photographs From Texas and Arkansas Prisons, Jackson recalls his initial visit to Cummins:

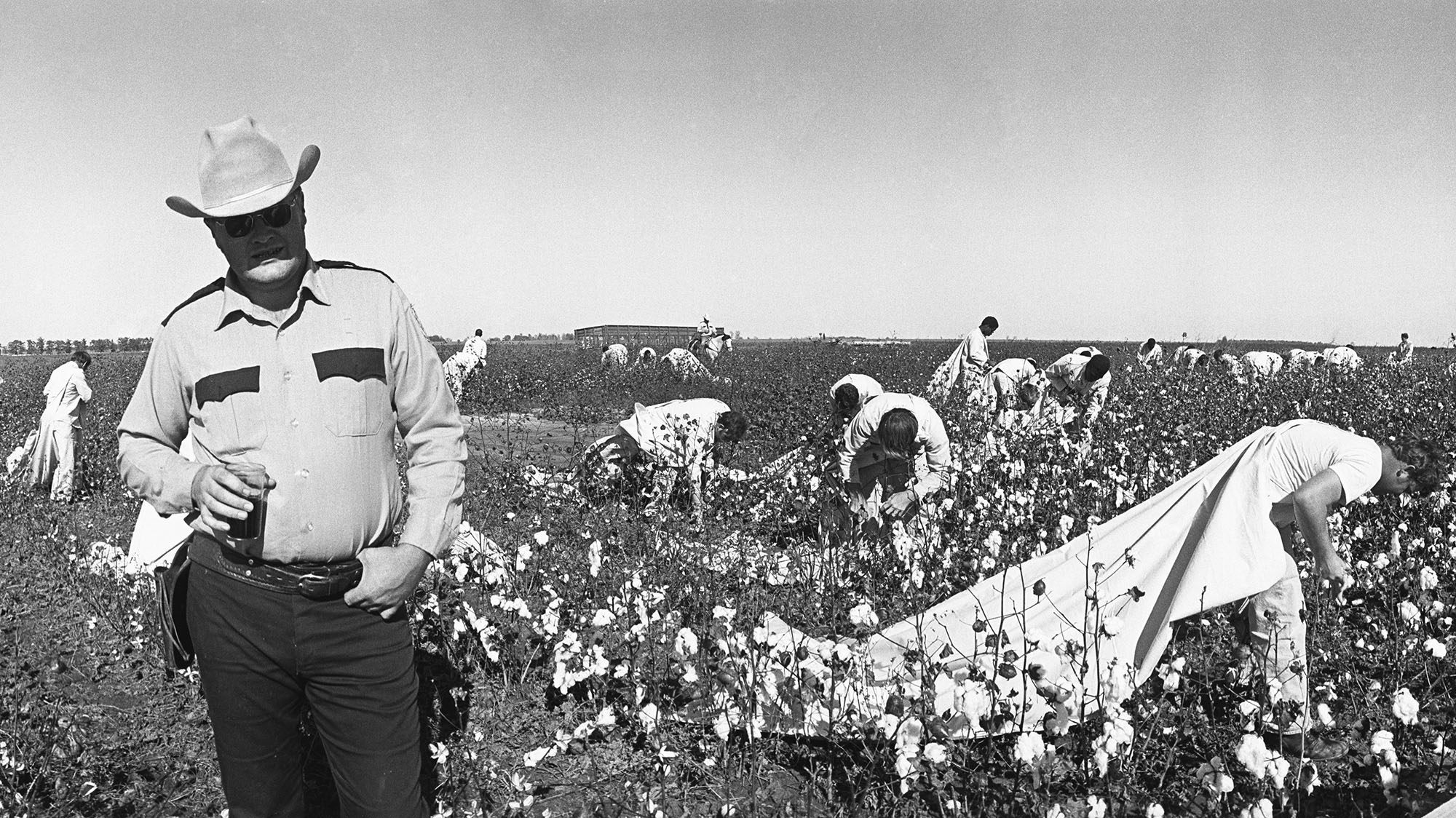

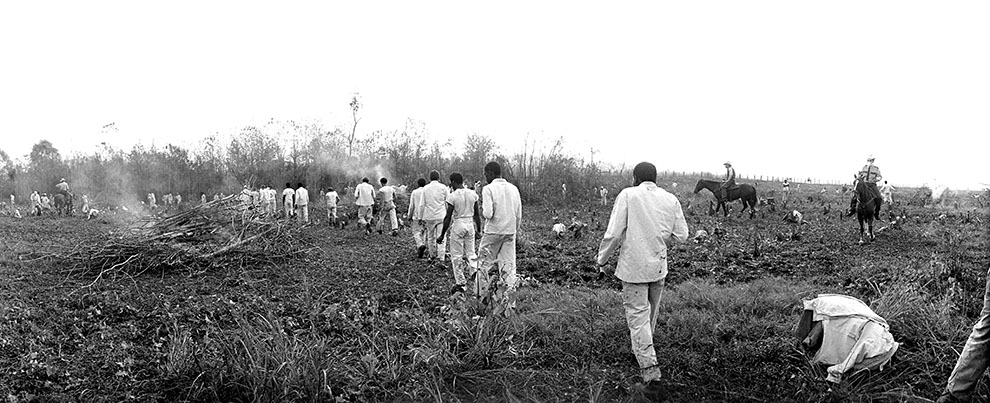

The first time I drove up to the road barrier, the armed man in khakis who asked me if I had any weapons in my car was a convict; during that visit, everyone I saw carrying a pistol, rifle, or shotgun was a convict guard. You could tell a person’s role from the clothes he wore: ordinary convicts wore white; trusties wore khaki, and the few civilian employees wore whatever they had. But just about everyone carrying a gun was a convict.

Despite Hutto’s mandate to improve Arkansas prisons, everyday life behind bars and in the cotton fields remained harsh and monotonous, as Mother Jones reporter Shane Bauer writes in an excerpt from his new book on the intertwined history of private prisons and prison labor:

In a federal hearing on prison conditions in Arkansas, inmates testified that failure to pick one’s quota of cotton was grounds for a punishment called “Texas TV.” A prisoner would be forced to stand with his forehead against a wall and his hands behind his back. He would be left there for up to six hours, often without food, sometimes naked. […]

Another inmate testified that he had been beaten with blackjacks, stripped, and left naked in an unlit “quiet cell” for 28 days for refusing to labor in the fields. Guards blasted air conditioning into his cell without giving him a blanket and fed him only bread, water, and a pastelike “grue,” causing him to lose 30 pounds.

In 1974, a federal court ruled that under Hutto, Arkansas prisons continued to hold prisoners in “sub-human” conditions and subjected them to “torture and inhumane punishment.” It also called out the continued use of armed inmate guards.

Jackson made eight trips to Cummins, including a visit in 1975 when he brought a Widelux camera, shooting panoramic images of the 16,000-acre prison farm. His shockingly candid work documenting these prison farms helped define the popular idea of life on a Southern prison. He’s produced a number of books of this work, including Inside the Wire, Doing Time on a Southern Prison Farm, and Cummins Wide.

Cummins prison farm, 1975

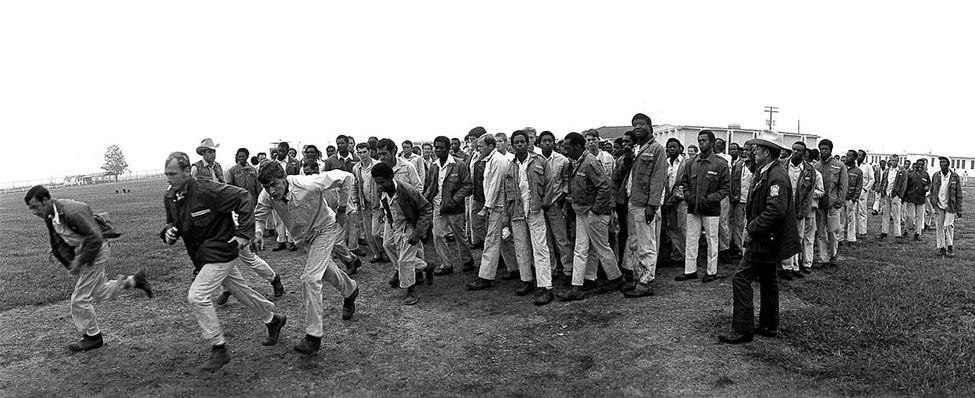

Convict guards waiting to go to the fields at Cummins Farm Unit, 1971.

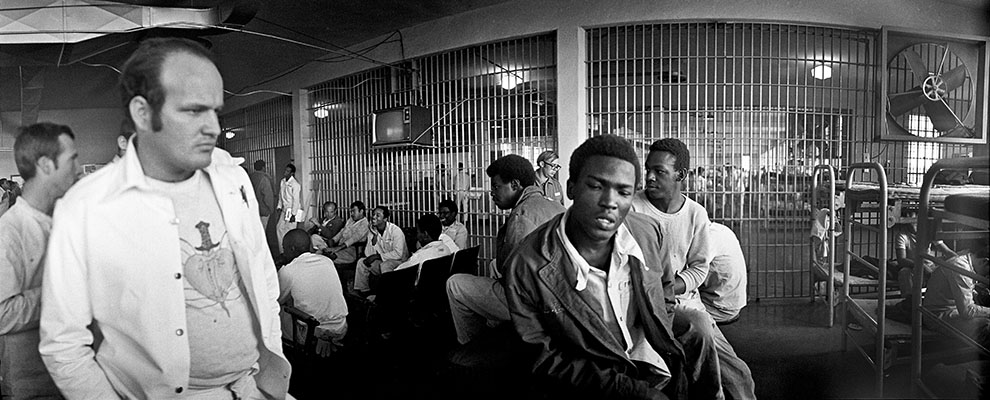

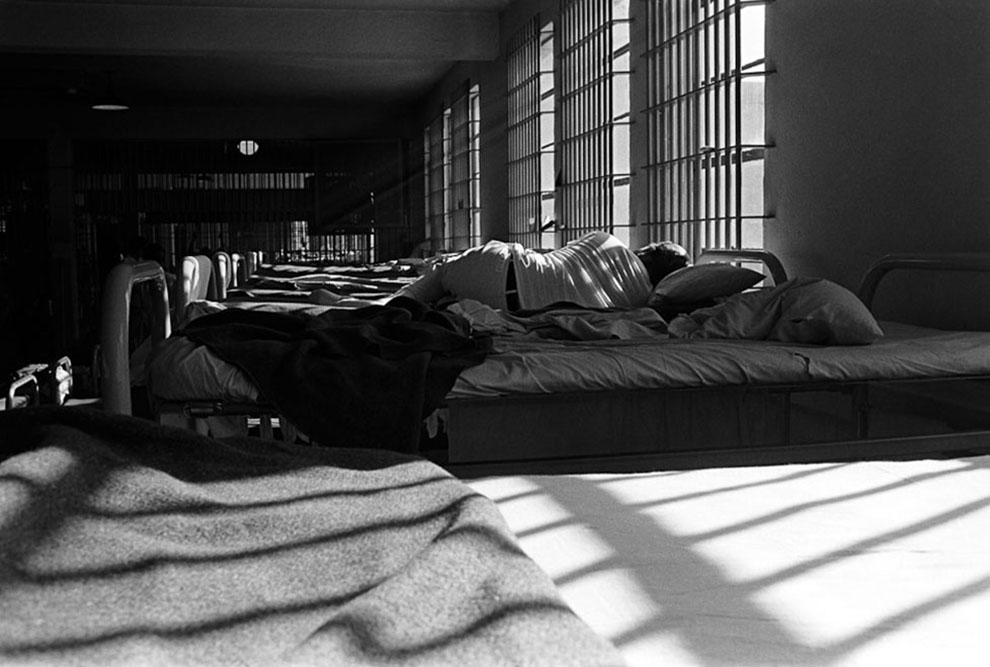

Inside Cummins

Cummins mess hall, 1975

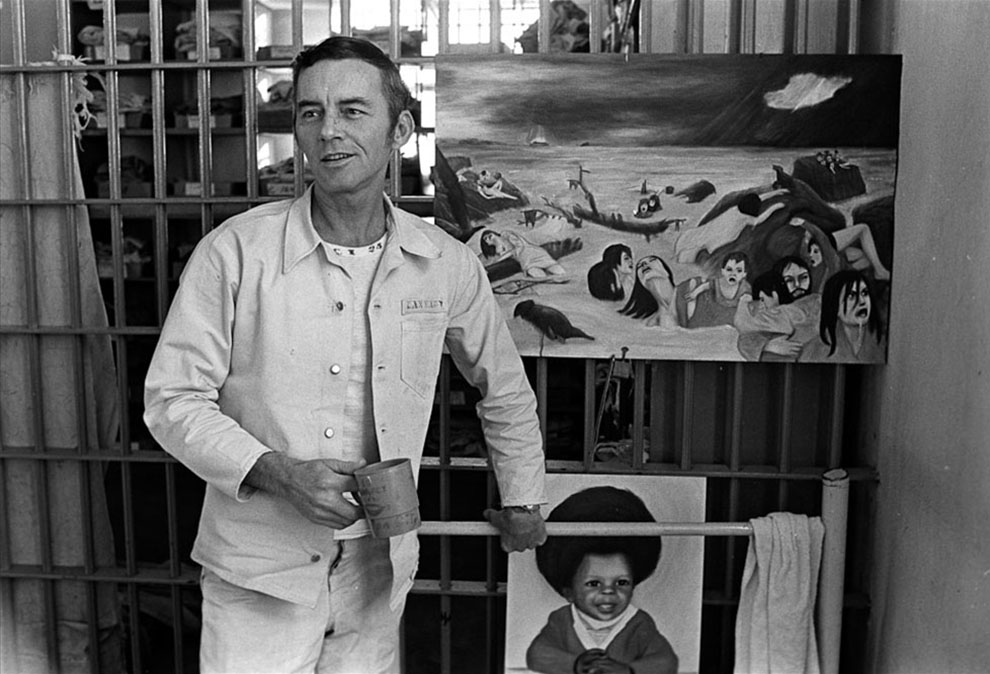

Inmate with paintings

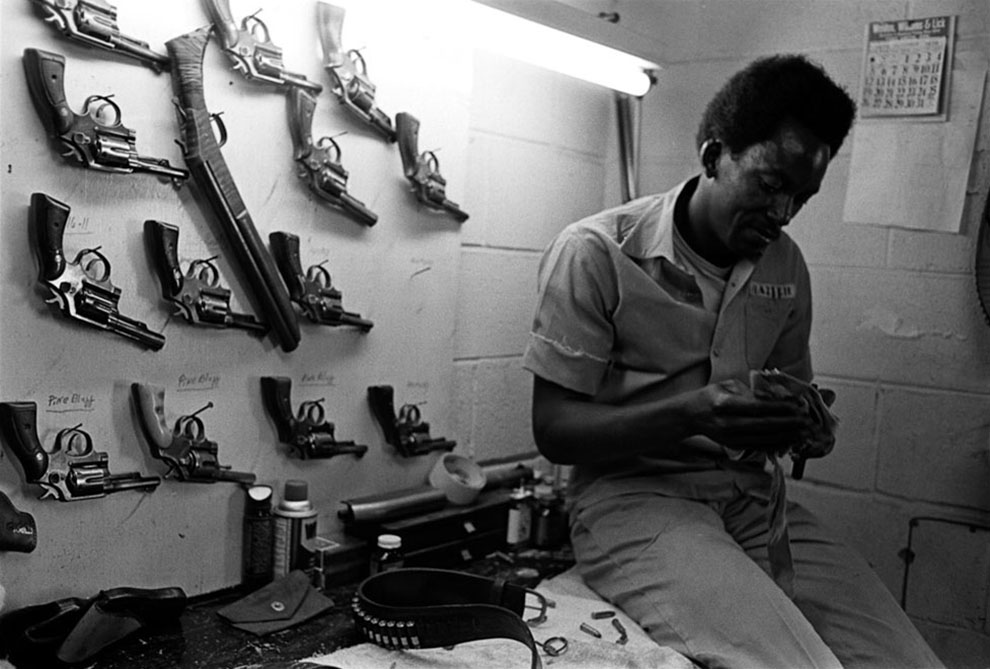

An inmate cleans guns, 1975

Cummins, 1974

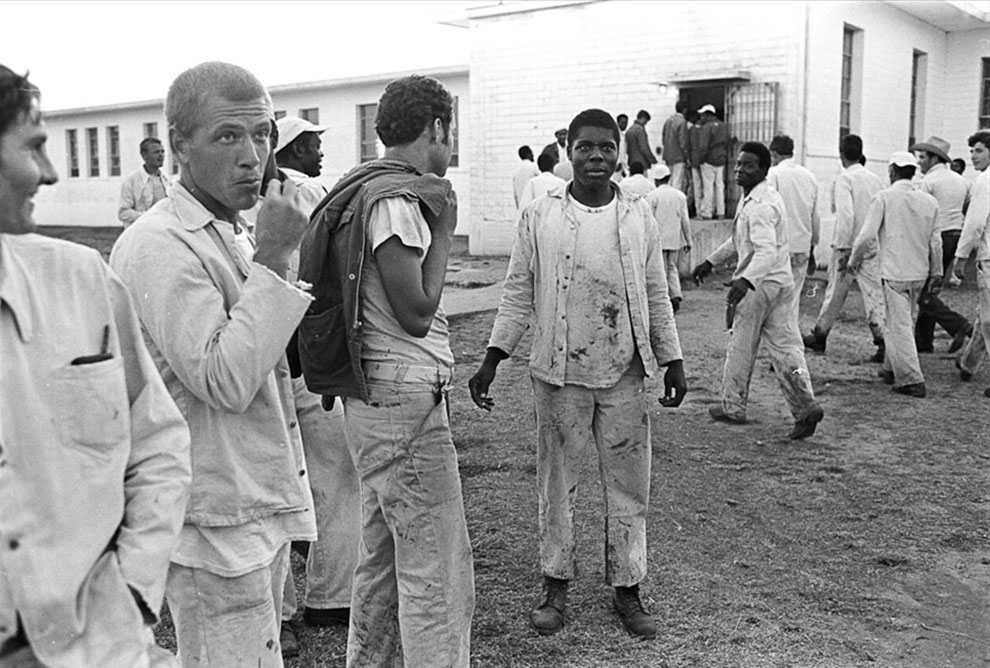

Prison yard, 1975

Guards on horseback, 1975

Cummins prison farm, 1975

Cummins prison farm, 1975

Cummins prison farm, 1975