Niall Carson/PA Images via Getty Images

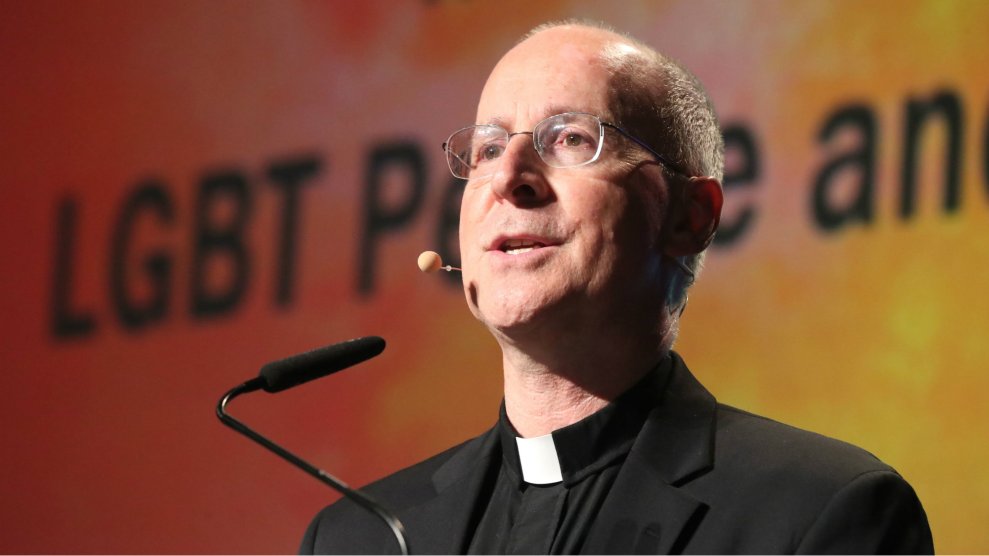

On a warm Saturday evening in August, Father James Martin, S.J. was driving home from a wedding in Lambertville, a small city in northwestern New Jersey, when his phone buzzed. The sprightly, 57-year-old Jesuit priest had just returned from Dublin, where he urged members of the World Meeting of Families—a multi-day celebration of Christian views on marriage, love, and the family—to “never underestimate the pain that LGBT people have faced.” Martin’s invitation to appear at the conference, which required a sign-off from the Vatican, outraged the increasingly vocal members of the Church who abhor Pope Francis’s progressive advances and see Martin, a longtime liberal commentator on Catholic issues, as Enemy No. 1 for publishing Building a Bridge, a blueprint for improving relations between Church officials and queer Catholics.

While he was on the road, a conservative Catholic website published an 11-page “testimony” from Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the Vatican’s former diplomat to the United States and one of the pope’s most vigorous right-wing critics. Viganò excoriated the corruption at “the very top of the Church’s hierarchy” and accused Francis of ignoring sanctions placed upon an American cardinal who had been accused of sexual abuse. Plus, he charged, the pope had tacitly permitted “the homosexual networks present in the Church” to flourish” by encouraging “pro-gay” enablers. Viganò’s Exhibit A was Martin, whose appearance in Dublin served only to “corrupt the young people” there. By the time Martin arrived home, the letter was major news across the world and his friends were bombarding him with messages.

More than just a historic rebuke of a sitting pope the letter was a call to conservative prelates sidelined by Francis and eager to reopen the debate within the Church over homosexuality. “There are some Catholics who believe that the Catholic Church and western civilization will survive or collapse depending on the Catholic Church standing by traditional doctrine,” says Massimo Faggioli, a professor of theology at Villanova University. “They think James Martin is the most dangerous enemy because he’s weakening Catholicism.”

Indeed, in a hierarchy where obedience and humility are paramount, no one serves as a better example for all that has gone wrong than the relentlessly outspoken Martin, the priest who counts Stephen Colbert and Martin Scorsese as friends and who The New York Times once dubbed the “scariest Catholic in America.” When I called Martin a few days after the letter was published, he seemed stunned by how personal the attack was. “I thought it was ridiculous,” he said. “It was like the Burn Book in ‘Mean Girls.'”

How Martin, a well-respected author with a flair for pop culture references, became a lightning rod for the social conflicts within Catholicism is a story as much about one man as it is a reflection of the extraordinary position the Church has found itself in during Francis’s papacy. Still grappling with allegations of sexual abuse by priests that burst into the open in 2002, progressive Church leaders have struggled to quash the persistent theory—propagated by Francis’s critics on the right—that mainstream acceptance of homosexuality is the root cause of clerical abuse. The Church’s inability to modernize its approach to homosexuality, even as a supermajority of Americans now accept it, mirrors its backward-looking approach to other hot-button issues.

Indeed, the American Church no longer commands moral authority on other social concerns like birth control, and divorce, with many practicing and devout Catholics simply ignoring some of their church’s admonitions. But even as Mass attendance plummets nationwide and traditional strongholds like Los Angeles and New York pay out millions in settlements with victims of abuse, the Church is flourishing in the American South. To this more diverse flock, “the scariest Catholic in America” has become a leader in expressing a new vision for an institution that, to its skeptical followers, has become irrelevant at best and spiritually compromised at worst. Especially concerning the full recognition and acceptance of LGBTQ Catholics.

The product of a “lukewarm Catholic” family in the Philadelphia suburbs, Martin never spent a day in Catholic school, for instance, or stood at the altar assisting the priest at Mass—the two most common entry points for aspiring clergymen. As an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, he studied finance and gained a reputation as the “floor Catholic” among his hall-mates in the Quadrangle, Penn’s 123-year-old system of dormitories. “Jim told the most irreverent Jesus jokes imaginable,” says Jacque Follmer, a classmate and close friend.

Religion only became a serious part of Martin’s life years after he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and took a job in human resources for General Electric in Connecticut. Channel surfing one night he came across a documentary about Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk and writer. Returning to work the next day, he couldn’t shake the contrast between his office job and a life that had deeper meaning. He began reading Merton’s books, including The Seven Storey Mountain. Soon, he would discover the Jesuits, a religious order that blended prayer with real-world action and told his parents that he was going to become a priest. “My family hit the roof,” he recalls. “Crying. Hysterics. My friends all thought I was crazy.”

After 11 years of training that included stops in Chicago to study philosophy and a service mission to Jamaica with Mother Teresa’s nuns, Martin was ordained in 1999. That same year, he published his first book, This Our Exile: A Spiritual Journey with the Refugees of East Africa. A memoir of two years he spent working in Nairobi with East African refugees, the book recalled a time of deep emotional conflict for Martin. While overseas, he fell in love with someone and considered leaving the Jesuits. After consulting with his spiritual director, Martin stayed the course.

His development as a Jesuit would continue until 2009 when he received final vows—the equivalent of being in the Mafia and becoming a “made man,” he says. After ordination, his first assignment was at America, the Jesuit magazine in New York where as a novice he had penned TV reviews and gained a facility with pop-culture references that evades most clerics. He began to write books that combined memoir with Church history and spirituality. Before publishing Building a Bridge last June, his most popular book was Jesus: A Pilgrimage, which tours 1st-century Galilee in a part-historiography, part-spiritual excavation of the life of Jesus. His other books have titles that illustrate the combination of theology and accessibility—The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything: A Spirituality for Real Life and My Life With The Saints—that has made him increasingly renowned in Catholic circles as a witty, reverential writer with a knack for explaining dense religious topics to a lay audience.

Even during the conservative reign of Pope Benedict XVI, Francis’ predecessor, Martin was outspoken and unafraid to question Church leaders. As early as 2002, Martin criticized the “tragically wrong decisions” made by bishops during the sexual abuse crisis and condemned the link between homosexuality and pedophilia which many conservatives made at the time and continue to make now. “It reveals this malignant strain of homophobia that runs through the Church,” he recalls. “The suffering of children was used to beat up on gay priests.”

But after Omar Mateen stormed into the Pulse nightclub in Orlando on June 12, 2016, killing 49 mostly gay people in what was then the deadliest mass shooting in American history, Martin’s role as a prominent Catholic shifted dramatically. Hours after the news broke, Martin took to Facebook for a live video. Wearing his traditional black clerical garb and collar, he ripped Church leaders for neglecting to use the tragedy as a way to reach out to the LGBT community. “It shows how the LGBT community is invisible still in much of the Church,” he said. “Even in their deaths, they are invisible.” More than 1.6 million people viewed the video.

Modern Catholic doctrine has condemned homosexual activity as “intrinsically disordered” and a “serious depravity” since 1975. Rather than minister to queer Catholics, Church leaders have devoted more public statements to helping parents and family members “cope with the discovery of homosexuality” in a loved one. Even Francis, whose progressive leadership on environmental issues and immigration inspired some hope for reform, once urged Italian bishops to reject applicants to the priesthood who may be gay and compared the theory underpinning transgender identities to nuclear weapons. The harsh rhetoric has lent itself to outright discrimination in some places too. At least 80 people—mostly teachers at Catholic schools—have been fired from Church-run institutions due to their sexual orientation in the past decade, according to America magazine. Martin has faced his fair share of backlash just for speaking out as an ally. Several of his recent speaking engagements have been cancelled, moved offsite from their original location, or inundated with right-wing protesters. Conservative Catholic websites have compared him to “a wolf in shepherd’s clothing” and “the smoke of Satan.”

When we spoke about the Church’s sordid history on welcoming queer Catholics, Martin said, “I’m not going to challenge Church teaching.” Still, he acknowledged that he could not support the premise that gay men should be barred from the priesthood. “I know many healthy, celibate gay priests. I know hundreds of them,” he said. As for the pope, Martin said he is a fan, but added, “He is, let’s be blunt, your 82-year-old Argentine grandfather who may have certain experiences and prejudices and thoughts that some of us don’t have.”

Young, liberal Catholics had known Martin more from his frequent guest appearances on the Colbert Report than for any theological significance to his writings. But the Pulse shooting—and his outraged reaction to it—immediately made him the authoritative voice on American Catholicism for the social media generation. Sister Jeannine Gramick, the co-founder of New Ways Ministry, a pro-LGBTQ Catholic organization, said Martin is “a man of justice” whose social media savvy has allowed an inclusive Catholic message to reach a new generation. Gramick’s advocacy for LGBTQ Catholics led the Vatican to “permanently prohibit her from any pastoral work involving homosexual persons” in 1999. The letter officially sanctioning her and New Ways Ministry cofounder Father Robert Nugent, S.D.S, was signed by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who would eventually take the regnal name “Benedict XVI” once he became pope in 2005. During a podcast last year, Martin said he believes Gramick should be a saint. “Here’s this woman who has really struggled and has really fought, and has really advocated, at great cost within her own church,” he said.

In 2017, two years after Francis reorganized the Vatican’s communication office into one standalone entity, he tapped Martin as an adviser, an extraordinary honor for an American priest, let alone one without the advanced degrees usually required for Vatican appointments. In California, a bishop began holding prayer services with Martin’s book as a guidepost. “He is one of the few leaders in the American Catholic Church who is known and read outside of the West,” Faggioli said. “He’s becoming a global figure.” That influence has extended to the center of the Vatican. According to Rocco Palmo, who writes about the Church for his influential Whispers in the Loggia site, Francis has requested and read Martin’s books, including Building a Bridge.

Now in her seventies, Gramick described Martin’s impact in a more personal way. “I feel like his spiritual mother or godmother,” she chuckled. “I’m so happy with what he’s been able to accomplish—how the Church has been able to grow because of him.”

But global figures attract controversy, which became obvious last spring when Martin was asked to speak at the World Meeting of Families conference in Dublin. News of his invitation sparked widespread protests among his traditionalist critics and a petition quickly gained more than 10,000 signatures asking him to withdraw because he supports “transgenderism for children” and “favors homosexual [sic] kissing during Mass.” On the same weekend as the conference, a far-right Catholic group organized a separate, two-day event to counter the “watered-down” approach to Church teaching promoted by speakers like Martin.

“A lot of what Father Martin says is very ambiguous. He’s a very clever man, he’s a very gifted speaker, [but] he revels in ambiguity and sowing confusion at a time when the laity in particular, and families, don’t need these clerical politics,” Anthony Murphy, one of the organizers, told the Catholic news service Crux in an interview. Influential conservative leader Cardinal Raymond Burke, who participated in the rival conference, condemned priests who support Martin, given his “open and wrong” position on homosexuality.

Even Martin’s brief appearance at the conference—for an hour-long speech and book signing—was revolutionary in its own right. At the last World Meeting of Families conference in Philadelphia, the only event for queer Catholics was a panel led by a gay celibate Christian that carried the Church’s official line on homosexuality. Three years later in Dublin, the Vatican permitted Martin to ask at an officially sanctioned Church event: “Is it surprising that most LGBT Catholics feel like lepers in their own church?”

While pacing a stage in front of a wall-to-wall crowd, Martin elaborated on six key insights that would seem obvious to anyone attending an East Coast dinner party, but came off as truly radical at an event coordinated by the Vatican. “Parishes need to remember that LGBT people and their families are baptized Catholics,” he said. “They are as much part of our church as Pope Francis, the local bishop, the pastor or any other parishioner.” He went on to offer 10 ways to better welcome queer Catholics, including “apologize to them,” “include them in ministries” and avoid reducing them “to the call to chastity we all share as Christians.”

After wrapping up, Martin took selfies with attendees and signed copies of his books. To one woman in a yellow sweater and dark overcoat, he added an inscription, which Martin said he heard first from a fellow Jesuit: “God loves you and your Church is learning to love you.”

During Martin’s talks with LGBTQ Catholics and their families, he likes to tell stories from the New Testament to illustrate how Jesus welcomed those who society shuns. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus encounters a tax collector, one of the most despised members of the community, among a huge group of people. and singles him out to share a meal. “This is how Jesus treats people who feel on the margins,” Martin told guests at the World Meeting of Families. “He seeks them out before anyone else; he encounters them, and he treats them with respect, sensitivity and compassion.”