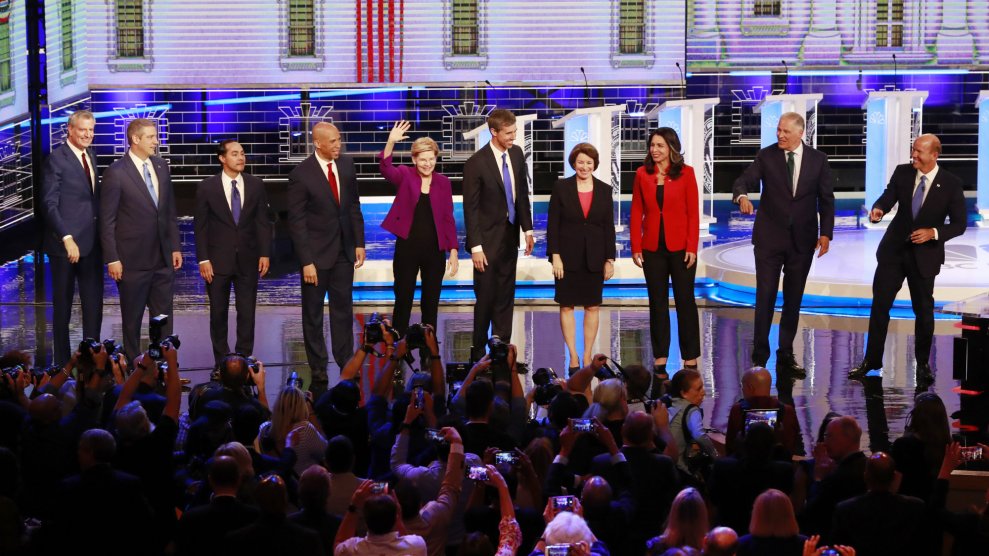

Sabina Crocette and London Croudy in the backyard of Crocette’s West Oakland townhouse.

Cayce Clifford

When she first got out, little things like crossing the street were difficult for London Croudy. “When you’re in prison, the only thing you’re thinking about is going home. You plan all these things in your mind, and then all of a sudden you get out and reality hits you,” Croudy says. “They are like, ‘Go find a job and get this ID,’ and you’re like, ‘Oh my god, Uber—what the hell is that?’ I feel left behind sometimes.”

After serving eight years of a 13-year sentence for conspiracy to distribute heroin, Croudy was released to live in a halfway house in Oakland, California, run by the private prison company GEO Group. She had to share a room with several people, and the beds and food were similar to those in prison. She had an hour of rec time and a strict curfew. “Just pretty much a step over incarceration,” she says. “Still walking around with fear.”

That changed when she met Sabina Crocette, a lawyer who was working at a prisoner-rights nonprofit. They started hanging out, and when Croudy asked Crocette if she knew anyone with an extra room to rent, Crocette remembered a new pilot program she’d heard about: the Homecoming Project, which pays people with a spare room to house those returning to the community after long prison sentences. Crocette had previously taken in formerly incarcerated people with mixed results, but she’d connected with Croudy and wanted to try it again. About two months later, Croudy moved in.

Croudy tears up remembering the first time she saw her new bedroom in Crocette’s West Oakland townhouse. Croudy assumed she’d basically be sleeping on the floor, but after she saw the queen-size bed and dresser dotted with fake candles, “this peace just came over me,” she says.

Few formerly incarcerated people land in such welcoming accommodations, particularly in the Bay Area’s absurdly overpriced housing market. In Alameda County, where the Homecoming Project operates, 4,800 people returned from state prisons in 2014. About one-quarter of the county’s residents have a criminal history, and at least 20,000 people—disproportionately people of color—face housing instability because of their records. So the Oakland-based nonprofit Impact Justice looked to Airbnb’s model and flipped it on its head as a way to offer affordable, stable short-term housing. Since Impact Justice started the Homecoming Project in August 2018, it has settled 12 formerly incarcerated people in private homes, rent-free.

“There’s hidden assets in our midst, and if we were able to pay the homeowner for housing someone coming home from prison, what would that look like?” says Terah Lawyer, Homecoming’s program manager. There’s “a level of desperation” among people leaving prisons, she says, because “housing is such a great need and one of the biggest fears of individuals coming home.” Applicants have told her that they’d be happy to sleep in a box in someone’s backyard. “They will settle for less because they think that they deserve less,” she says. “I always try to tell them, ‘You are worth way much more than a cardboard box.’”

Croudy and Crocette knew each other beforehand, but that isn’t typical of the program’s pairings. Would-be tenants go through an extensive screening and matching process, answering questionnaires covering their bedtimes, cooking habits, and pet peeves. Hosts are asked whether there are drugs, alcohol, or weapons in the house. Once a pair is matched, they meet and can reject the other for any reason. Ultimately, housemates sign a six-month agreement, and the host gets a monthly stipend of about $750. During that time, the Homecoming team works with tenants to find more permanent housing.

Beyond providing shelter for a vulnerable population, the project aims to remove the stigma surrounding incarceration. “How can the community heal the community?” asks Lawyer. “What sets it apart from traditional transitional housing programs is that the funding doesn’t go into some for-profit transition program. It goes into the community, stimulating the economy.”

When Croudy first saw her new room, she says “this peace just came over me.”

Cayce Clifford

Providing stable housing for former prisoners seems like a no-brainer: It reduces recidivism and prison populations, saving taxpayers money. Yet people getting out often have to hunt for space in shelters, sober living facilities, or halfway houses. Going it alone is virtually impossible for anyone with a criminal record, little money, and no credit or rental history. Finding decent housing is even harder for people who have finished long sentences. In part because they are less likely to reoffend, few programs serve them. Yet typically this group needs the most help, which is why the Homecoming Project primarily focuses on people who served 10 years or more.

Long-standing challenges to housing formerly incarcerated people have become more acute as California’s housing crisis deepens and criminal justice reforms chip away at decades of tough-on-crime policies. In California, statewide reforms reduced a quarter of the prison population between 2008 and 2018. At least 30,000 people are released from state prisons every year. The 2018 First Step Act has also led to thousands of early releases from federal prisons. Formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the rest of the public.

Lawyer knows these challenges firsthand. After serving 15 years in prison, she was placed in a residential treatment facility in San Francisco. She couldn’t visit her family. She had to attend 30 hours of treatment classes weekly for a substance abuse problem she didn’t have. “In fact, I’m a certified drug and alcohol counselor that is able to facilitate the same classes that I was subjected to take,” she says. Program restrictions also kept her from starting the job she had lined up before leaving prison.

She used her experience to shape the Homecoming Project, which tries to foster independence while offering participants and their hosts extensive support. For hosts, the program offers workshops on conflict resolution and what it’s like to be incarcerated. A “community navigator” acts as a case manager and life coach. One participant, Jesse Vasquez, went to prison as a teenager and served 19 years for attempted murder. In his first two weeks out, his community navigator went with him to the DMV and the doctor’s office, and to get his birth certificate. “He would stand there in line with me, guide me through the process. He taught me how to navigate a cellphone, how to set up email,” Vasquez says. The community navigator also brought Vasquez to volunteer at a food pantry and introduced him to new neighbors. “He was essential in kind of helping me get my roots into the community.”

Adjusting to life on the outside, Vasquez says, “there’s a sense of an arrested development.” The first time he took a bath, he filled the water too high, and when he got in, it overflowed. His first time cooking in his new home, he set off the fire alarm and panicked that the cops or paramedics would show up. “The problem was that I was still thinking that I’m still 17. But here I am, I’m 36, and how do I interact in an adult world?”

While the Homecoming Project’s dozen placements are a small sample size, the results have been promising. All current and former program participants have jobs. Vasquez is pursuing a degree in child development and psychology while working with two nonprofits. Croudy works with a criminal justice group and is starting a multimedia platform to share the stories of formerly incarcerated women. Of the six people who have completed the program, three have gone on to live independently, while the others, including Croudy, have continued to live with their hosts under a separate lease agreement. Looking ahead, the Homecoming Project hopes it can help organizations outside the Bay Area replicate its model.

Eight months into living together, Croudy and Crocette have settled into a comfortable routine. Croudy no longer asks permission before making a move in the house, and Crocette doesn’t worry whether she should introduce Croudy as her “sis,” “new family member,” or just “housemate.” “London didn’t need a mother. She didn’t need a sister. She didn’t need a mentor. So just kind of learning the process of letting go a little bit,” Crocette says. “The intention was to make her feel welcome. At the same time though, it’s the balance of recognizing the person’s independence.” Sitting close to Crocette on the couch in their backyard, Croudy interjects, “The beauty of our two different walks in this same situation is that, in fact, I did need her. I did. [She] gave me the motivation and the confidence and the ease to be able to do these things.”

“She’s the one who sat me down,” Croudy adds, “and was like, ‘Hey, you don’t have to ask that. You’re a grown woman. Be you.’”