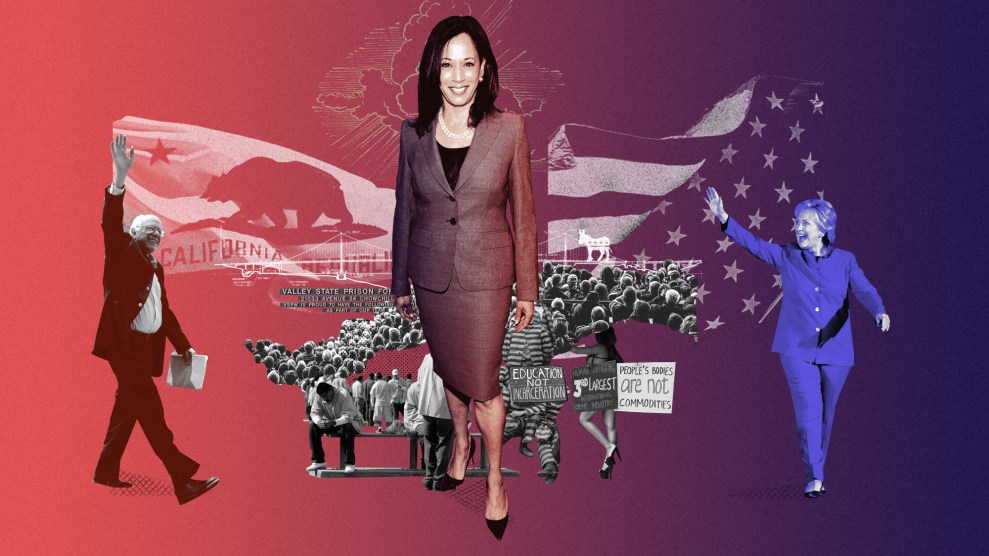

Mother Jones illustration; Christian Gooden/Zuma

They didn’t say her name directly, but Kimberly Gardner knew that Donald Trump’s supporters were trying to smear her on the first night of the Republican National Convention. Gardner is the chief elected prosecutor in St. Louis, a position that might not normally get national attention. But over the past few months, the president and other Republicans have criticized her office for filing felony charges against a white couple who pointed guns at Black Lives Matter protesters marching through their gated community. At the convention, the couple, Patricia and Mark McCloskey, gave a speech from their mansion, with serious expressions on their faces as they warned they were being treated unfairly.

“What you saw happen to us could just as easily happen to any one of you who are watching from quiet neighborhoods around our country,” said Patricia McCloskey, who has claimed she feared for her life when the protesters walked past their house. “They actually charged us with felonies for daring to defend our home,” Mark McCloskey added, criticizing the reform-minded approach that Gardner and some other Democratic prosecutors have taken to try to make the criminal justice system more fair for people of color. “Whether it’s the defunding of police, ending cash bail so criminals can be released back out on the streets the same day to riot again, or encouraging anarchy and chaos on our streets, it seems as if the Democrats no longer view the government’s job as protecting honest citizens from criminals, but rather protecting criminals from honest citizens.”

Gardner isn’t a stranger to criticism. Since she was first elected in 2016, Republicans in Missouri have pushed back against her attempts to send fewer people to prison for low-level offenses, and to hold police accountable. In recent months, Trump has railed against her for charging the McCloskeys, as have the Republican governor and attorney general in her state. Days before the Republican National Convention kicked off this week, I caught up with her to hear her side of the story. We talked about the death threats she receives, the way Trump has made her job harder, and whether she thinks other Black women prosecutors, including former prosecutor Kamala Harris, face double standards on the job.

You won your primary election earlier this month in St. Louis, after facing some pretty intense pushback from President Trump and other Republicans about some of the recent charging decisions you had made. How are you feeling about the victory?

I feel humbled that the people of the city of St. Louis continue to reelect me to continue reforming the system that we all know needs to be not only reformed, but rebuilt—dismantled and rebuilt to be fair and just for all.

During the campaign, you filed charges against a white couple who pointed guns at peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters. Trump said it was a “disgrace” that you filed charges against them. You’ve mentioned that you received quite a bit of hate mail after he criticized you. Were you surprised by this response?

First of all, I was surprised that the president of the United States would inject himself in the prosecutorial discretion of a local prosecutor, who investigates and reviews potential criminal activity in their jurisdiction, which we do every day without fanfare or political pandering. Second, it increased the death threats that I got, and it put myself and my family in danger. The president chose to misdirect his energy, with other Missouri officials, the AG, as well as the Missouri governor and Senator Josh Hawley, to pander to a base, to racially divide, when we should be focused on this COVID-19 pandemic.

People were protesting outside my house. I was called a Marxist, I was called a tyrant. People put a Hitler mustache on my picture that I was using to run for reelection, and I had the most vile death threats where a person would say they wished a bullet was put in my head, that I was hung from the tree by the KKK. I was called everything under the sun that I will not say here, but it’s the intersection of race and gender that was perpetuated by a president, who instead of bringing us together in this daily pandemic, he chose to stoke the racial fear and divide in a community for no reason.

That’s so awful. And it sounds like you’re facing pushback in other ways too. The Missouri legislature is soon going to consider a bill that would allow the state’s Republican attorney general to take some of your powers, and to actually prosecute some of the murder cases in your jurisdiction. This seems pretty unusual—normally it’s rare for politicians to question the discretion of a top elected prosecutor like yourself. But obviously it’s not the first time something like this has happened to you, and to other Black women elected prosecutors. Do you feel like the standards are different for you than they are for white men or even white women who are working as elected prosecutors?

That’s a very good question. Our prosecutorial discretion has been challenged in many ways, even different from our male counterparts in the reform movement. And Black female reform-minded prosecutors face a level of vitriol that is different from our other counterparts in the same space. And it’s these acts of dehumanization that become a normal everyday process in other jurisdictions, like for Marilyn Mosby in Baltimore, Kim Foxx in Chicago, Aramis Ayala in Orlando, and Diana Becton in California. When you look at these examples of the vitriol we get—hate mail, we receive caricatures of our faces, demonizing us and dehumanizing us—it really [shows] that the African American female has been the most disrespected individual in any civil rights movement. Females in general. And so we have to address why.

And we have to address why prosecutorial discretion has been a sacred proposition for prosecutors around the country, but now when you have reform-minded African American female prosecutors, why is it now that our discretion is challenged every day? And by the way, the [Missouri] attorney general also believes in prosecutorial discretion, and actually signed on to an amicus brief when he, amongst other attorney generals around the country, chimed in to support the overturning of the plea of guilty for General Flynn. So why is it that he can advocate for prosecutorial discretion and go so far to say that it is the benchmark proposition—that a prosecutor [deciding] when they bring charges, who to bring charges against, and what charges to bring—is so crucial to the criminal justice system in our country, [and why] is that prosecutorial discretion different when it’s in the state of Missouri?

So that’s what we need to have him answer, as well as the governor. Because they are also having a method of removing me as the sitting circuit attorney—he wants to propose a removal statute for myself. And one of the issues the governor is pushing, he talks about incompetence. It’s just these veiled, thinly veiled racial, sexist attacks that are perpetuated by individuals who want to do nothing more than to misdirect, to cause fear and divide, and to look away from their failed leadership to address the pandemic, the growing deaths in Missouri.

And as far as the veiled racism, or even explicit racism, that you mentioned, you filed a lawsuit in January accusing the city of a racially motivated conspiracy to undermine you and push you out of office. And at the time, several other Black women prosecutors, including some that you’ve mentioned, like Marilyn Mosby from Baltimore, Rachael Rollins in Boston, flew out to St. Louis to support you. I’m curious, behind the scenes, do you all still keep in touch and try to support each other in other ways? Like what kind of relationship have you developed with these other prosecutors?

We have become sisters in this most unique time. Prosecutors in this most unique time. And we support each other. Anytime one of them needs help, of course I’m a phone call away. Anytime they need me to support them, like they’ve done for me many times, I will show up and be there for them. Because it’s not just that you run for office and you are a reform-minded prosecutor. You have attacks and vitriol put at you, and actually putting your family in danger. Most other elected officials have not experienced the same level of violence and dehumanization. And so we support each other by saying it’s going to be okay and you always can lean to one of them because they know what you’re going through. This is not saying our other reform-minded colleagues who may not experience the same level of backlash do not support us also. They support us and come out. But we have a unique relationship because of the vitriol that’s pushed toward us. We all come together.

You and many of these other Black women progressive prosecutors have faced pushback in part because you aren’t following the traditional blueprint for how prosecutors normally act. Historically, elected prosecutors have often prioritized convictions and sending people to prison. Can you talk about how you see the job differently?

I think that’s the mistake, that most people think the reform-minded prosecutors are not traditionally prosecuting. Actually we are traditionally prosecuting, but we look at crime as a public health crisis, we look at crime on a continuum, and we use a model of harm reduction and public safety. We look at who we charge, what we charge, when we charge, and we focus our resources on those violent individuals and those crime drivers that we should be focusing our case load on. So it’s not saying that we’re sacrificing prosecutions or not traditionally prosecuting, but you know, we look at how we can address low-level nonviolent individuals in a more holistic way where they’re not going further in the crime continuum and we’re not making them more violent individuals in the future. We look at crime on a continuum, but we’re not sacrificing public safety.

I also want to ask you a bit more about this term “progressive prosecutor.” You and Kim Foxx and Marilyn Mosby and others have often been described this way. There are some critics who say that prosecutors can never actually truly be progressive—because they are still working on convictions and putting people in prison. Do you think that the label of “progressive prosecutor” is sort of tricky?

Well, I think that when they say “progressive,” really they should talk about the minister of justice. I think progressive-minded prosecutors want to bring the office back in line with the true vision and mission of a prosecutor, to be a minister of justice. What we’ve done is talk about convictions and a one-size-fits-all flawed approach of mass incarceration that has made our communities less safe for decades. And we have to address the harm, we have to address the systemic racism that exists in the criminal justice system. We also know we have to address the accountability of police—even policing is not immune from systemic racism.

I want to talk a bit more about that, because this summer the conversation has mainly been about police reform. How do you balance maintaining a working relationship with law enforcement for your job while trying to find ways to hold them accountable? And has your approach to this changed at all since George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis?

We have to pursue justice, the laws of the jurisdiction we represent, and police accountability is one of the No. 1 reasons why most violent crime is unsolved, in terms of mistrust with the criminal justice system. So if you’re trying to address violent crime in your jurisdiction, you have to address that no one is above the law, even law enforcement. When you have the ability as a police officer to take someone’s life or liberty, you have to make sure they are trustworthy and hold them accountable like everyone else. And that’s why we have the first formal exclusion list in the city of St. Louis as well as in the state of Missouri, to make sure testimony from police officers is trustworthy. We have to make sure we continue the conversation that led to the 8 minutes and 46 seconds of the death of Mr. George Floyd that has sparked protests around the country, saying, “Enough is enough” and “Police accountability is crucial.” We have in our jurisdiction racism in the police department, and it needs to be addressed, because that makes the community feel safe as well as police officers feel safe who work in that environment, and it makes people police better in the streets. So it’s a complex situation, and of course as a prosecutor you’re always going to have an adversarial relationship on issues with law enforcement, but we work well with law enforcement every day. We couldn’t do our job if we did not have law enforcement. What we don’t work well with is the police union that has a one-sided view, a biased view, on keeping the racial rhetoric going to divide the community, and so that’s where we have pushback.

That’s really interesting. I also want to ask you a bit about Kamala Harris, who has also called herself a progressive prosecutor. She made history when she became Joe Biden’s running mate, becoming the first woman of color on a major party ticket. But her background before she was a senator, as a district attorney and attorney general in California, is controversial. So I’m curious, do you agree with her that she was a relatively progressive prosecutor when she served in those roles from 2004 to 2017?

I believe at that time she was the first of everything. Progressive prosecution did not exist five years ago. When we talk about progressive prosecuting, that is a concept that really started about five years ago, post-Mike Brown. But at the time, Ms. Senator Kamala Harris started the foundation of the progressive ideas of what a prosecutor could do, addressing the root causes of what drives individuals to the criminal justice system. And at that time, that was progressive.

How do you think the public’s view of her record is shaped by some of the double standards that we discussed earlier that Black women face in this role?

African American females, particularly a prosecutor, are going to have this unique kind of vitriol as we stated before, and I think that’s what happens to Senator Kamala Harris. She has a record, she’s held some of the highest positions as an African American DA, as well as attorney general of her state, and so she’s had to make some tough decisions on a big level, but she’s set the tone for a lot of reform-minded prosecutors in terms of what a prosecutor can do from within the system to address some of the brokenness of the criminal justice system. People can look to her record, but I think in terms of her advocacy, in terms of reform, she understands the issues that we’re dealing with. I believe she understands police accountability and the need to address reform on many different levels. So I think she brings a lot of powerful skill sets that we need as the vice president in this trying time.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited.