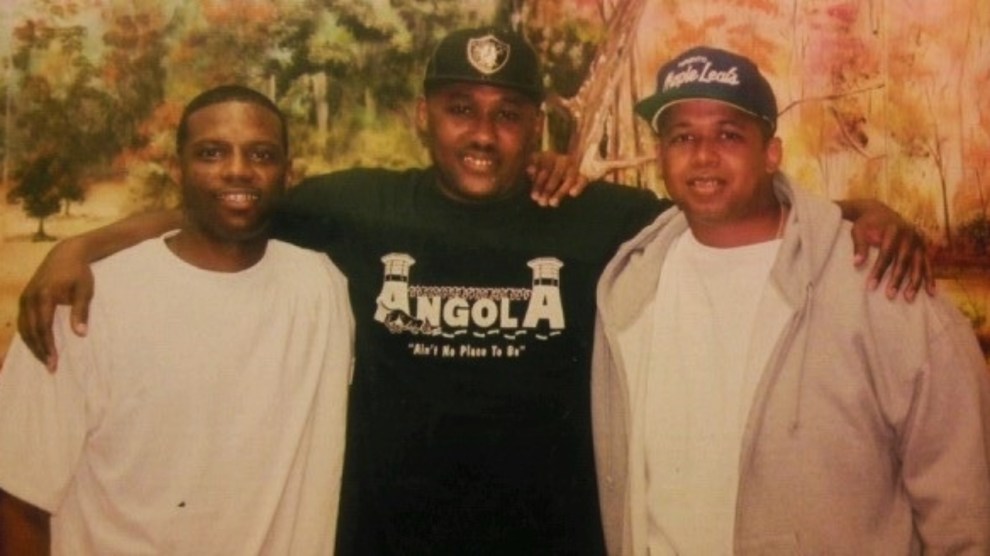

Roderick Vidau with two of his childrenCourtesy of Vidau's attorney

Roderick Vidau didn’t think the jury would convict him. In 2005, when Vidau was 28 years old, a police officer in Baton Rouge chased him down one night because he matched the description of a robber: tall, Black, and dressed in a blue shirt and jean shorts.

Vidau said he was innocent, and there was some evidence on his side. One man who’d been mugged that night reported that the robber took $10, and a woman said she’d been forced to hand over $5. Both thought the robber was armed. But when the police apprehended Vidau shortly after the alleged muggings, they didn’t find any money on him, or any weapons. And in court, one of the victims identified another person as the perpetrator.

Vidau turned down a plea deal, figuring at least some jurors would side with him. And he was right: Out of 10, two found him not-guilty. But in Louisiana, a Jim Crow-era rule allowed jurors to send people to prison even without a unanimous decision. Which meant that Vidau, accused of stealing $15, was sentenced to 35 years—more than two years for every dollar. He said goodbye to his children, who were just seven, four, and two years old.

White supremacists devised Louisiana’s split-jury rule during an 1898 constitutional convention, hoping to make it easier to convict Black people. One newspaper endorsing the change reportedly wrote that the rule would remove the need for “popular justice,” a euphemism for lynchings. And the measure was effective: In Louisiana, about 80 percent of people serving time today because of split-jury convictions are Black. Nearly two-thirds of them were sent to prison for life without the possibility of parole. And at least dozens of them were originally sentenced as children.

In April, the Supreme Court ordered Louisiana and Oregon, the only other state with a similar rule, to stop sending people to prison without unanimous convictions, arguing that this was unconstitutional. The 6-3 decision in Ramos v. Louisiana offered a glimmer of hope for Vidau and around 1,500 people in Louisiana who had exhausted their appeals and were serving split-jury sentences in state prisons. But there was a significant catch: The justices did not specify whether their ruling was retroactive, which meant that these men and women had to remain behind bars—at the worse possible time. The coronavirus was beginning to spread, and it was impossible to maintain any social distance in prison.

More than seven months later, the Supreme Court is finally returning to the issue, in a case that will decide what Louisiana and Oregon should do with people like Vidau who are actively serving time because of nonunanimous convictions. The case, called Edwards v. Vannoy, revolves around a Louisiana man named Thedrick Edwards who was convicted by a split-jury in 2007 of rape, armed robbery, and kidnapping. Edwards is Black, and the lone Black person on his jury voted to acquit him. If the justices rule in his favor and make their prior decision retroactive, Louisiana and Oregon would have to offer him, Vidau, and others like them new trials or plea deals.

Louisiana has argued that nonunanimous verdicts should be banned going forward, but that it would be too burdensome to reconsider all those old cases. Doing so would swamp the courts, Louisiana Solicitor General Elizabeth Murrill argued. “There can be no doubt that declaring the Ramos rule retroactive unsettles thousands of cases that involve terrible crimes in all three jurisdictions,” she told the justices during oral arguments on December 2. “Requiring new trials in [old] criminal cases would be impossible in some, and particularly unfair to the victims of these crimes.”

But according to research by the New Orleans-based Promise of Justice Initiative, the Louisiana Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and the Orleans Public Defenders, granting new trials would result only in two additional cases per district attorney on average. “Louisiana is the incarceration capital of the country—we already have a lot of court proceedings,” says Jamila Johnson, an attorney with the Promise of Justice Initiative. In the grand scheme of things, she argues, reconsidering these 1,500-or so old cases would not put much extra strain on the system.

It could be months until the Supreme Court announces its decision. In the meantime, I tried to schedule a phone call with Vidau, who’s currently locked up at the Elayn Hunt Correctional Center because of the $15 robbery conviction. He still has about two decades left on his sentence, which was so lengthy because the court considered him a habitual offender. He says he was arrested as a teen after riding in a car with friends who allegedly robbed a store, and though he reportedly maintains his innocence in that case, too, he accepted a plea deal at the time, which is common.

As the years continue to pass, he misses his family. His kids, who were young when he was first imprisoned, are now teens, and he regrets having missed so much of their childhood, their graduations and basketball games.

In the end, Vidau’s attorneys told me he couldn’t speak with me over the phone because the prison was back on lockdown, due to another surge in coronavirus cases. About 200 people have tested positive at Elayn Hunt since the pandemic began. Confined to his housing unit, Vidau also couldn’t listen to oral arguments for the Edwards case earlier this month, but he and the other incarcerated guys with him talked about it with anticipation.

“I think he understands that the decision isn’t coming” right away, says his attorney Sally Dahlstrom. “But you know, he knows he is sitting there in prison because of a nonunanimous jury, and I think it’s hard for him to understand why he’s still in there when the Supreme Court said it was unconstitutional.”