Solitary confinement cell in New YorkBebeto Matthews/AP

Once considered the death penalty capital of the United States, throughout its history Virginia has carried out more executions than any other state. Since 1976, when the Supreme Court reinstated the punishment, 113 executions have occurred there. But soon, when Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam signs the legislation that has passed the state legislature and is sitting on his desk, Virginia will join the 22 other states who no longer kill as a punishment. In doing so, it also will become the first southern state to abolish capital punishment completely. The sentences of the last two men remaining on the state’s death row—Anthony Juniper and Thomas Porter—will be automatically converted to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

In the midst of these victories in the fight against capital punishment, many advocates are attempting to address a different form of punishment, questioning how much more merciful life imprisonment is compared to the death penalty.

Life without parole has many of the same qualities that make the death penalty so abhorrent. Capital punishment is riddled with racial disparities, junk science, and a legal system that routinely fails the marginalized. “Those same exact flaws exist across the whole system,” says Ashley Nellis, a senior research analyst at the advocacy organization The Sentencing Project. Looked at logically, staying alive, albeit in prison, just has to be a better outcome than being executed. But looked at more closely, is the lesser sentence really “better” than the harshest one? “I would not call it a humane alternative to the death penalty,” Shari Silberstein, the executive director of the Equal Justice USA, a criminal justice nonprofit, tells me. In fact, it’s a punishment both extreme and one that disproportionately affects the most marginalized people.

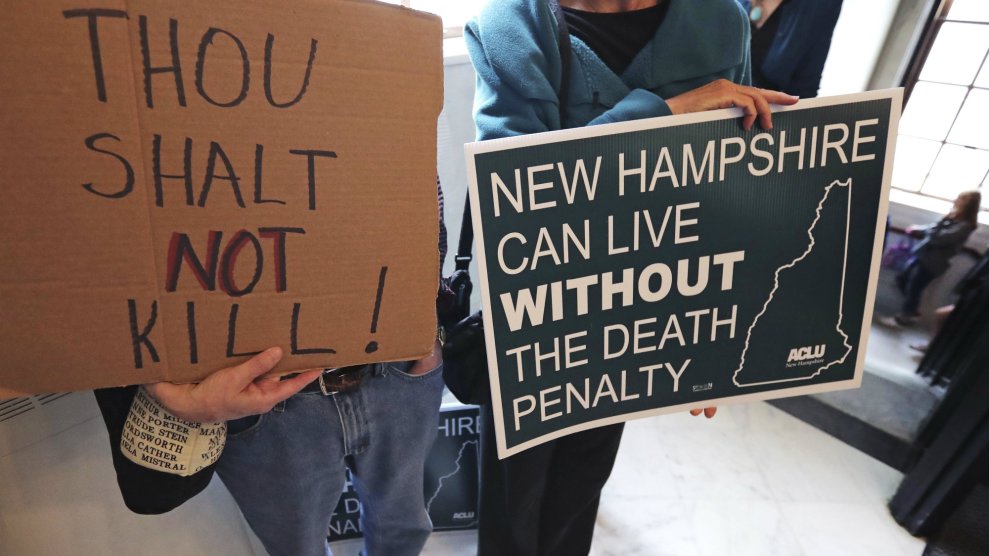

Despite the Trump administration’s last-minute killing spree on the federal level, the death penalty has never been more unpopular. In the last five years, four states have repealed the death penalty altogether, and many more haven’t held an execution in years. President Joe Biden, once a champion of harsh punishments, is the first president to oppose capital punishment and has pledged to abolish the federal death penalty. Wyoming and Ohio lawmakers have introduced legislation in their respective states to end the practice as well. All this activism to end the cruelest and most controversial punishment in the American criminal justice system has somehow left life without parole as the next best alternative—but a recent report from The Sentencing Project shows that for many compelling reasons, the punishment has a number of attributes that could compare in cruelty to death sentences.

In 2019, I began thinking about the implications of life in prison after spending some time in Nashville when Don Johnson was executed for the 1984 murder of his wife. After the governor declined to commute Johnson’s sentence, and he was put to death after more than 30 years on death row, I thought about the alternative activists and Johnson’s friends had called for. Call off the execution, they urged. Let Don live—until he died in prison of natural causes. But even a life spent behind bars has its own set of cruelties.

According to The Sentencing Project, more than 200,000 people are serving those life sentences, which means life without parole, life with parole, or virtual life sentences—in which someone is sentenced to 50 years or more. They represent one out of seven people in prison, and there are 22 times more people serving life without parole than the population of people awaiting death. Thirty percent of lifers are 55 years of age or older, and nearly 4,000 inmates serving life were convicted of a drug-related offense; 8,600 people serving life with the possibility of parole or virtual life were sentenced as minors.

The racial bias in the death penalty has been well-documented. Half of all murder victims are white, but 80 percent of capital trials involve white victims. Since 1976, 21 white defendants with a Black victim have been executed compared to 297 Black defendants whose victims were white. But, as Nellis tells me, “All of the arguments one makes for eliminating the death penalty are also true for life in prison.” Racial disparities also plague those sentenced to a life behind bars: More than two-thirds of people serving life are people of color. One out of every five Black men in prison are serving life sentences, and Latinx people make up 16 percent of the lifer population.

Throughout the United States’ criminal justice system, conditions for people serving life sentences vary depending on the state. But frequently those conditions can be just as harsh as those for inmates on death row, especially the pervasive use of solitary confinement. A 2013 study by the ACLU found that 93 percent of the 3,000 people awaiting death in prison are locked in their cells for 22 to 24 hours a day. Studies have shown that even a short period of time in solitary can cause psychological trauma resulting in hallucinations, panic attacks, and paranoia, not to mention an increased risk of suicide.

Only Connecticut enshrines solitary confinement for lifers in law, but it is routinely practiced elsewhere. As the Marshall Project reported, in 1987 William Blake facing drug charges in New York, shot and killed a police officer in a failed escape attempt. Unable to give Blake the death penalty, because the state had abolished capital punishment, the judge sentenced him to 77 years in prison. Deemed a high risk because of his first escape attempt, Blake now spends his days in solitary confinement in an area of the prison called the “Special Housing Units.” He once wrote, in an essay that was published in Solitary Watch, a project that showcases voices from solitary confinement: “Dying couldn’t take but a short time if you or the State were to kill me; in SHU I have died a thousand internal deaths.”

Then there is the 2010 case of Kalief Browder who spent three years in solitary confinement at Rikers Island in New York after being arrested for stealing a backpack—which he did not steal—at the age of 16. When he was finally released, he died by suicide two years later. Browder’s family believe that the intense torture and pain of those three isolated years drove him to take his own life. “Prison is a traumatizing place,” Silberstein says. “It doesn’t matter if you’re there for a year or the rest of your life.”

The legal options for those who are sentenced to life without parole are also far more limited than for those who are sentenced to death. Once someone is sentenced to death, the appeals process offers the defendant and his team of lawyers the opportunity to appeal the sentence, usually attempting to overturn it. If the state is going to put someone to death, the reasoning goes, it should be sure that the conviction is fair.

Clearly the system is far from perfect. Studies estimate that 4 percent of the people on death row are innocent; as of 2021, 185 death row inmates have been exonerated. Capital murder trials are plagued with police misconduct, false testimonies, and the use of questionable scientific evidence. I’ve written about executions of inmates with intellectual disabilities, severe illness, and ones with incompetent lawyers. But still, legal mechanisms to challenge the sentences exist—which does not occur for most lifers. In these cases, Nellis explains, “you don’t have capital-skilled attorneys, and you don’t have unlimited appeals.” Recently some states, like Michigan, have begun reviewing the life sentences for juveniles, but even then, many of those inmates have a short period of time in which to file their challenges, have trouble finding lawyers, and end up being unable to file appeals. “You have even fewer protections,” if you’re serving a life sentence, Nellis says. “It’s decades behind bars—with no way out.”

For Silberstein, anti-death penalty activists shouldn’t focus solely on life without parole as an alternative to the death penalty, but they should consider an entire reconfiguration of what justice means, and what it should look like. After someone has been harmed, “there’s a need for healing, safety, accountability, and a sense of justice,” she explains. But it is unrealistic to expect “that a prison sentence can meet all of those needs.” Clearly, they haven’t, she notes. Harsh sentences persevere, even in places where the death penalty has already been abolished because of the underlying belief that, as Silberstein explains succinctly, “The only sense that justice has been done is if someone else suffers.”

Perhaps now—when execution as a punishment has never seemed so obscene and unacceptable—it’s the right time to reconsider all punishments. What is the real difference between spending years behind bars only to die strapped to a gurney while correctional staff administer enough drugs to kill you, and languishing behind bars until so-called natural causes finally, mercifully, takes your life? Are these differences sufficient to end one punishment and while still justifying another? If the United States is on the cusp of abolishing the death penalty, perhaps it should take the next logical step and abolish another form of cruel and unusual punishment as well: life imprisonment.