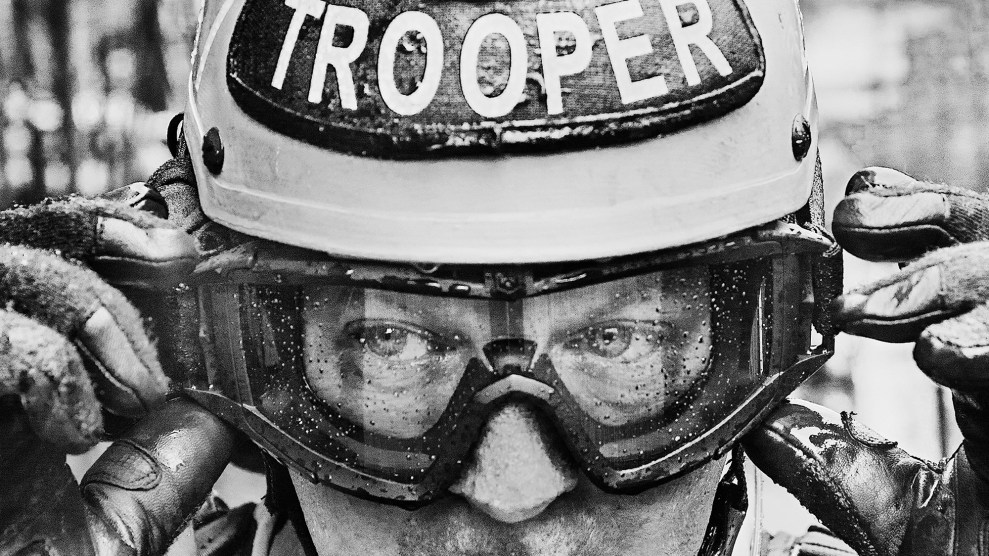

Stephen Zenner/SOPA Images/Getty

Second Lt. Caron Nazario was driving with temporary tags. The US Army Medical Corps officer had just purchased a new SUV and had a temporary cardboard plate taped to the inner rear window when two officers of the Windsor, Virginia, police department pulled him over for not having license plates, according to their report. But when Nazario, who is Black and Latino, pulled to a stop at a gas station, officers Joe Gutierrez and Daniel Crocker immediately drew their guns. Then they pepper sprayed him and shoved him to the ground. Nazario, who was in uniform, tried to keep his hands in the air as he repeatedly asked the officers to calm down. Videos of the encounter went viral in April, when Nazario filed a federal lawsuit alleging that the officers violated his right to be free from excessive force.

Gutierrez has been fired, and the state is investigating. But there’s a good chance they may never pay a dime to Nazario. In court filings this month, both officers claim their actions were protected by “qualified immunity,” which for decades shielded cops’ bad behavior when they’re sued in federal court. If a judge agrees, his lawsuit could be tossed.

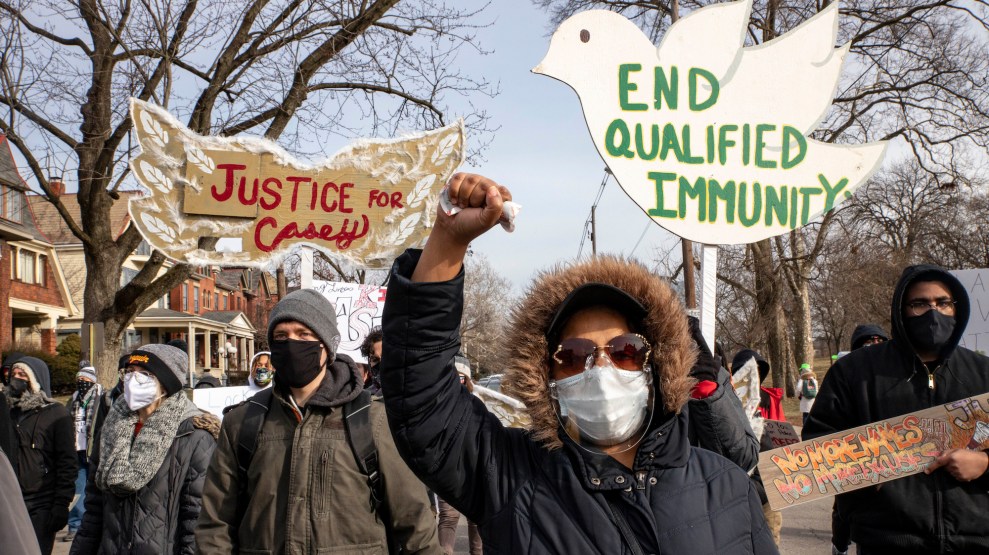

Qualified immunity has become a flashpoint in debates over police accountability in the year since former Minneapolis Police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd. The previously obscure legal doctrine is the subject of more than two dozen state and national bills seeking to limit, circumvent, or abolish it. Yet despite initial momentum, the reform effort has slowed. Congress remains mired in negotiations on the issue, and bills at the state level have had decidedly mixed success. In Virginia, state legislators repeatedly shot down attempts to create a pathway for police misconduct lawsuits that would take qualified immunity off the table for cops like Crocker and Gutierrez.

Qualified immunity was created in a series of Supreme Court decisions starting in the 1960s, which ruled that government employees cannot be held liable in federal civil court for violating someone’s civil rights—unless their conduct flew in the face of “clearly established” law. That, it turns out, is a high and often arbitrary bar to clear. As I reported last summer, for the law to be considered “clearly established,” a judge must have previously found similar actions in a past case with nearly identical facts to be unlawful. In practice, this standard lets cops off the hook for blatantly illegal behavior, simply due to a lack of precedent. In one prominent example, a court had previously ruled that “the Fourth Amendment prohibited unleashing a dog to attack a suspect who had surrendered by lying on the ground.” But later, when other police officers were sued for setting a dog loose on a suspect sitting with his hands in the air, a judge still granted qualified immunity and dismissed the case. The law wasn’t “clearly established,” according to that judge, because the suspect was sitting, not lying down.

In the weeks after Floyd was killed, limiting qualified immunity became the closest thing there was to a consensus issue in police reform. Marchers in the streets of Minnesota, New York, and Ohio lifted signs calling for its abolition. Polling repeatedly found strong public support for allowing civilians to sue cops for misconduct. And Congress took notice. The Ending Qualified Immunity Act in the House drew Democratic, Republican, and Libertarian co-sponsors. In the Senate, Indiana Republican Mike Braun introduced his own bill curbing qualified immunity. Fellow GOPers Lindsay Graham (South Carolina), Mike Lee (Utah), and Rand Paul (Kentucky) all signaled their openness to work on the issue. Another bill, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, first introduced last June and still in the works, proposes eliminating qualified immunity for cops, as well as banning chokeholds, carotid holds, and no-knock warrants.

Yet despite that initial momentum, prospects for nationwide qualified immunity reform have dimmed. The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act is the furthest along, but it’s far from certain if it will pass—or if it will include limits on qualified immunity in its final form. After getting through the House a second time this March, the bill is stalled in closed-door negotiations, with Congress poised to blow past the May 25 deadline President Joe Biden set for the anniversary of Floyd’s death.

The reason? Republicans. “We’re back a little bit to more traditional partisan battle lines, which is a really unfortunate place to be in police reform right now,” says Ed Erikson, director of the Campaign to End Qualified Immunity, a national advocacy campaign co-chaired by ice cream moguls Ben and Jerry (Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield have long been known as political progressives). Over the last year, the campaign has worked with civil liberties groups to push both state and federal legislation, and increasingly come up against GOP opposition. Erikson points to the role of former President Donald Trump, whose administration called qualified immunity reform a “nonstarter” last summer. “You have some of those Republicans who were willing to take a courageous and moral stand on something where there’s bipartisan public consensus, shrink back into their turtle shells and just not want to get railroaded by a rogue former president,” Erikson says.

A lot of the change also has to do with the Fraternal Order of Police, the powerful police union that has staunchly opposed both state and national qualified immunity reform efforts, arguing that abolishing the doctrine would hurt police recruitment and bankrupt individual officers for doing their jobs. “It’s hard for lawmakers to explain to their local police chief why they aren’t standing with them and why they don’t have their backs,” Erikson says. Braun, for his part, pulled his bill after facing FOP pushback and attacks in a Tucker Carlson interview.

Without federal action, states have been taking steps on their own. In Colorado last year, legislators passed a first-of-its-kind state law making it easier for civilians to sue the cops. Strictly speaking, the new law doesn’t abolish qualified immunity, which is a federal doctrine. But it allows people whose rights are violated to bring police misconduct lawsuits in state, rather than federal, court. And it bans police from claiming qualified immunity as a defense in those state cases.

Colorado’s new law is, in a sense, revolutionary, because it creates a brand new pathway for civil rights enforcement. The legislation harkens back to Reconstruction, when the federal government passed Section 1983, a part of the Ku Klux Klan Act. The 1871 law gave people the right to sue government employees in federal court violating their rights under the US Constitution. “The idea, at the time, was that states could not be trusted to protect the constitutional rights of their citizens,” says Joanna Schwartz, a professor at UCLA who researches qualified immunity. “Here we are, 150 years later, and the federal courts, in the view of many states, can no longer be trusted to protect the constitutional rights of their citizens because of qualified immunity, along with other barriers.”

In January, a Black mom in Aurora, Colorado, became the first to pursue a lawsuit using this new pathway. Last August, trying to make up for months of being cooped up inside due to COVID, Brittney Gilliam planned a “Sunday funday” for the girls in her family. She’d take her 17-year-old sister, two teenage nieces, and her 6-year-old daughter to get their nails done at a local salon in Aurora, Colorado, before they all went out for ice cream. But when they pulled up at the salon that morning, it was closed. So Gilliam started searching for other nail spots on her cell phone. That’s when police approached her blue SUV, pulled the family from the car at gunpoint, and handcuffed most of them as they lay facedown on the ground. Gilliam and her girls were detained for two hours. The Aurora Police Department later said its officers had approached the SUV as a “traffic stop” because the car had the same license plate number as a stolen motorcycle from Montana.

Gilliam and her family filed a civil lawsuit against the officers who detained her family, accusing them of racial bias and violating the family’s rights against excessive force and unlawful search and seizure. And because the officers can’t claim immunity, the family’s case may stand a better chance than thousands of federal police misconduct lawsuits filed each year, such as Nazario’s. If they win, the officers who detained them at gunpoint may be required to pay 5 percent of damages, up to $25,000 of their own money. (The rest would come from the local government.)

Following Colorado’s lead, New Mexico and New York City also created alternate paths for civil rights lawsuits and banned qualified immunity as a defense in those cases. Connecticut and Massachusetts passed more limited reforms. Yet in at least 17 other states, bills to circumvent qualified immunity are still pending or have failed over the last year, according to the Campaign to End Qualified Immunity. Many of those bills have faced the same growing political headwinds as the national legislation. While Colorado’s law passed within 16 days of introduction last summer, backed by overwhelming bipartisan support, New Mexico’s, a year later, had to overcome uniform Republican opposition. In Minnesota, where Democrats hold the state House but Republicans control the Senate, a bill with a qualified immunity provision similar to New Mexico’s “doesn’t have a pathway at the moment,” says Julia Decker, policy director of the ACLU of Minnesota. The Republican leader of the Minnesota Senate has drawn a red line on the issue.

And in Virginia, where a bill creating a way around qualified immunity has come up for votes repeatedly over the last year, and failed, opposition from police unions is deterring Democrats, says Robert Barnette Jr., president of the Virginia State Conference NAACP. “The police association is very, very strong in their advocacy,” Barnette explains. But the state NAACP isn’t giving up the cause. In April, after the video of Nazario being pepper sprayed went viral, the state NAACP began pushing for a bill to in a special legislative session. “We tried to make sure people understood that qualified immunity by itself was detrimental to policing in Black and brown communities,” Barnette says. “It’s on the top of our priority list, I can tell you, because we feel like if we can change the behavior of law enforcement, some of these minor traffic stops won’t end up in fatalities.”

Still, no states can end qualified immunity entirely. That would take a ruling from the Supreme Court—which has repeatedly rejected opportunities to do so—or an act of Congress. Because Democrats in the Senate don’t have the votes to overcome a potential filibuster of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, they now are trying to strike a deal with Republicans for a compromise bill that would again have to pass both houses of Congress. As negotiations continue, it’s looking like qualified immunity reform will be on the chopping block. Earlier this month, House majority whip Rep. James Clyburn (D-South Carolina) indicated he was willing to give up that part of the proposal. Yet other House Democrats are digging in their heels. “As a result of qualified immunity, police killings regularly happen with virtual impunity,” ten Democratic representatives wrote in a letter to congressional leaders last week. “It’s long past time for that to end.”

In April, Sen. Tim Scott (R-South Carolina), who is leading the GOP side of negotiations, floated the gist of a compromise: Individual officers might continued to be shielded in civil court, but the police departments that employ them could be sued instead. Presumably, this policy would incentive departments to crack down on or fire abusive officers. The text of Scott’s proposal hasn’t been made public, but Schwartz believes it isn’t such a bad idea. “When a police officer is wearing a badge and a gun that are given to him by a city or town and then uses that authority in a way that violates people’s rights, this city or town bears some responsibility for that as well.” Schwartz says. As it is, cities or police departments almost always pay out settlements or judgements on behalf of individual cops who are successfully sued. But Schwartz argues there should be partial liability—”financial sting,” as she puts it—written into the law for officers found responsible for violating civil rights. “There also has to be some consequences for individual officers,” she says.