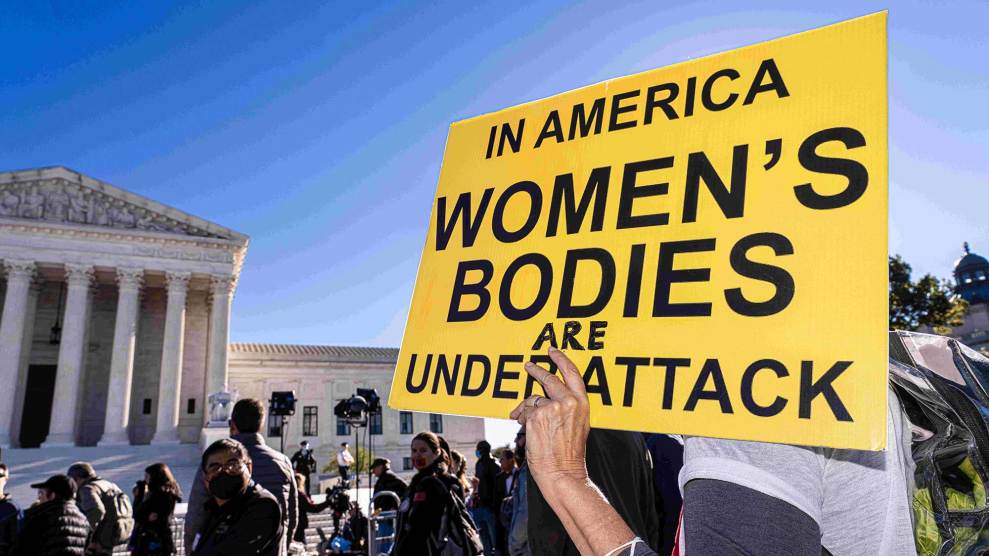

Ryan C. Hermens/Associated Press

When news broke last Friday that Lizelle Herrera, a 26-year-old resident of the Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas, had been arrested and charged with murder for allegedly having a self-induced abortion, reproductive rights advocates on the ground sprang into action to raise awareness of her case—and challenge the charges against her. They were successful: just two days later the local district attorney dropped all charges, admitting that, even under Texas’s six-week abortion ban, “it is clear that Ms. Herrera cannot and should not be prosecuted for the allegation against her.”

How did Herrera end up behind bars with a half-million-dollar bail for something that is not a crime in Texas? The district attorney hinted at what had gone wrong when he acknowledged in the same statement that someone at the hospital where Herrera had sought care first reported her to the sheriff’s office.

This chain of events is not unique: The truth is that medical staff have long reported pregnant people—predominantly women of color—for things they think might be illegal, or otherwise disapprove of.

As a reproductive justice reporter, I’ve followed many of these cases over the years. Back in 2011, Bei Bei Shuai was charged with murder after attempting suicide while pregnant. As the Guardian reported: “When her baby Angel died in her arms…Shuai was so distraught she was instantly transferred to the mental health wing of the Methodist hospital in Indianapolis. Grief stricken and under heavy sedation, she was unaware that within half an hour of her baby’s death a detective from the city’s homicide branch had arrived at the maternity ward and had begun asking questions.” She spent over a year in jail before pleading guilty to criminal recklessness.

Four years later, another pregnant Indiana woman, Purvi Patel, was convicted of feticide and neglect of a dependent after taking abortion-inducing drugs. She’d gone to the hospital after experiencing severe bleeding where an attending physician called the police. Patel spent three years behind bars.

Cases in which women are reported by medical staff for allegedly using legal or illegal substances while pregnant are common—whether they cause a miscarriage or not. Just this fall, a woman in Oklahoma (which has since passed a near-total ban on abortion) was sentenced to four years in prison for having a miscarriage. Prosecutors argued that the 20-year-old’s methamphetamine use was the cause, though a medical examiner testified there were fetal abnormalities that were likely to blame. In 2017, a 29-year-old California woman with a history of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia was 37 weeks pregnant when she started cramping. She went to her local hospital, where she had a stillbirth. Doctors reported her to local police and child services for using drugs—she was jailed two days later and is still fighting her case. In 2019, an Arizona hospital social worker reported Lindsay Ridgell to the Department of Child Services—who was also Ridgell’s employer—for using medical marijuana to treat her hyperemesis gravidarum during pregnancy. Her name was added to Arizona’s central child abuse registry and only removed last month when an appeals court ruled in her favor. And in 2020, Kim Blalock was charged with a felony after she told doctors at the hospital where she delivered that she’d taken her hydrocodone prescription in the final months of her pregnancy (prosecutors dismissed the charges against her earlier this year).

In the United States, the history of these cases is deeply connected to the War on Drugs and its racist surveillance and policing of people of color and Black people in particular. In Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction and the Meaning of Liberty, legal scholar Dorothy Roberts explains that “charges of ‘prenatal crime’ used to occur twice a decade. Then, in the mid-1980s, prosecutors decided to tackle the panic over an alleged explosion of ‘crack babies’ by prosecuting their mothers.”

Medical staff were a key part of that system. In 1989, at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, a nurse named Shirley Brown believed she was witnessing a rise in use of crack among her pregnant patients. She approached the Ninth Circuit Solicitor, who was responsible for prosecuting all cases in the county, Roberts explains in Killing the Black Body. Solicitor Charles Condon quickly contacted the hospital and arranged for law enforcement to begin operating there, under the guidance of nurse Brown. They would begin testing all pregnant women who they suspected of drug abuse—and those who tested positive were arrested. Of the thirty women arrested at MUSC during the five years that the hospital’s policy was in place, twenty-nine were Black. The one white woman arrested had a Black boyfriend (Brown, it’s worth noting, believed that miscegenation was against God’s will).

Four years later, two of the women arrested at MUSC filed a class action lawsuit against the hospital and the City of Charleston—supported by an attorney named Lynn Paltrow. On March 21, 2001, the Supreme Court ruled in the arrested mothers’ favor: MUSC’s policy of drug testing patients without their consent violated the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable searches.

Despite that victory, cases of pregnant people being turned in for alleged drug use has not gone away. “We think that most hospitals don’t know about the Ferguson decision,” says Dana Sussman, deputy executive director of the National Advocates for Pregnant Women. “It’s been a really underutilized Supreme Court decision.” Although it’s technically illegal for public hospitals to share nonconsensual drug tests with police, many hospitals contact child services instead—which then shares the same information with law enforcement. Today, 24 states and the District of Columbia consider substance use during pregnancy to be child abuse under civil child-welfare statues, whether or not in causes harm to the fetus.

This all might seem tangential to what happened to Herrera, but what’s important to understand is that doctors and medical staff are in many cases literally empowered by state law to intervene when they believe a pregnancy person has caused harm to their fetus. In other cases, like that of Purvi Patel, in which the physician who called the cops was a member of an anti-abortion group, doctors may feel personally obligated to report. And in yet other situations, medical staff may be outright confused about what their responsibilities are. That’s even more likely the case as anti-abortion laws are passed on a near-daily basis. Given the amount of fear that laws like Texas’s SB 8 have caused—doctors have voiced concerns about performing even emergency procedures like ending an ectopic pregnancy—healthcare providers may actually be afraid that they could be sued for not reporting a self-managed abortion.

“The medical presentation for a miscarriage is indistinguishable from a self-managed abortion,” says Sussman. “Both will be and are suspect, particularly for communities already surveilled by police and the family policing system—and even more strikingly if someone has a history of drug use, or discloses drug use or any other behaviors that providers or police deem as posing a risk to the fetus.”

After I shared my research on hospital reporting on Twitter, my feed was flooded with stories from hundreds of patients who’d been questioned by their doctors, from parents who’d been separated from their children, and even from caseworkers wondering what other options they had has mandatory reporters. They wanted to know: What are doctors and hospitals required to report, and how can patients protect themselves?

When it comes to self-managed abortion, no policies currently require medical professionals to report the person. And because there is often no medical way for a doctor to tell whether a patient ended their pregnancy with abortion pills or simply miscarried, unless the patient discloses information about an abortion, the doctor may never know.

Obligations to report suspected drug use is slightly more complicated. When doctors and caseworkers encounter a patient who tests positive for an illicit substance, many believe they are required to report that patient to child protective services under a set of laws called CAPTA and CARA. But Sussman says there’s a lot of confusion around what the law requires.

“People assume that it requires drug testing,” says Sussman. “What it actually requires is anonymized notification to the local child welfare authority if a baby is exhibiting symptoms of being substance affected.” Instead of reporting individual parents, hospitals must submit an anonymous report saying, for example, four babies this month had fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

“There’s no federal law that requires testing and reporting. And every state is different,” says Sussman. “People need to really understand what their mandated reporting laws do and don’t do. She recommends referencing the nonprofit Elephant Circle’s mandatory reporting guide for practitioners.

If someone is reported, Sussman says, they should call NAPW—or, if they self-managed their abortion, they can reach out to If/When/How’s Repro Legal Helpline.

“We can step in really quickly,” says Sussman, “and call the DA and educate folks on what the law actually says versus what the what they think the law says.”