Update: On Oct. 27, presumably thanks to the article discussed below, the Burleson County district attorney’s office cleared Anthony Graves of all charges and ordered him released after 18 years in prison. Read Pamela Colloff’s fabulous followup story, “Innocence Found.”

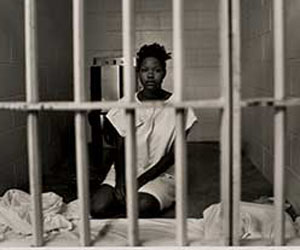

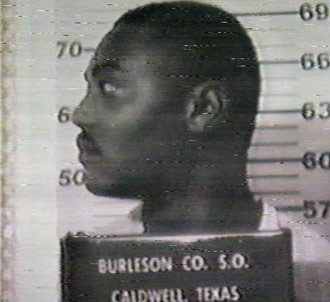

Imagine it. You’re 26 years old. The police show up at your mom’s apartment. Cuff you. Drag you down to the station and throw you in a holding room without explanation. You sit for half an hour. Nobody will tell you a thing. Finally a justice of the peace shows up, reads you your rights. Says you’re charged with capital murder. You don’t know what kind of Kafka nightmare you’ve been dragged into, but you do know it’s a colossal mistake. That you need to get it cleared up right away. “Capital murder,” you repeat, stunned. You repeat it 18 times, enunciating the syllables as though trying to grasp the meaning. As you are hauled off for interrogation by the Texas Rangers, you slap the side of your head, crying out, “Am I dreaming?”

Today, more than 18 years later, your case still hasn’t been cleared up. Your most productive years have been squandered on Texas death row, and even now, after your hide was barely saved by a last-minute appeal, and the court threw out your conviction due to the most egregious sort of prosecutorial misconduct, the Texas authorities are attempting to retry you for a crime you didn’t commit. A crime perpetrated by the man you barely knew—who fingered you and then recanted, both to the prosecutor before your own trial, and then again, just prior to his own execution for the crime, insisting he and he alone killed the members of that family as they slept. A crime for which, in your case, there is no motive. No physical evidence to implicate you. For which you have an alibi.

Your name is Anthony Graves, and you had nothing to do with any of this.

In a stunning new article, Texas Monthly senior editor Pamela Colloff dedicated more than 14,000 words to this tragicomedy of errors, poor judgment, legal snafus, and prosecutorial dirty tricks that robbed a man of his best years and may yet rob him of his life. It’s a lot to take on (the second-longest piece in the magazine’s history), especially given that we tend to yawn when death row inmates proclaim their innocence. But Graves’ case was so fatally flawed from start to finish that you will likely finish Colloff’s piece, as I did, wondering why the prosecutor isn’t the one behind bars—and why those who came later are still insisting Graves should be tried, found guilty, and executed.

There may be some hope for Graves amid this spectacular farce. Colloff’s story is exactly the kind of in-depth journalism that, with a little luck, could pressure the authorities to right a terrible injustice. So hats off to the author.