The X-shaped building cluster is Pelican Bay's special housing unit.<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Jelson25">Jelson25</a>/Wikipedia Commons

As Americans gear up to celebrate Independence Day, several dozen inmates languishing in solitary confinement at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison are standing up for their rights the only way they can think of—by refusing to eat. The prisoners, who are being held in long-term or sometimes permanent isolation, launched a hunger strike Friday and have sworn to continue it until prison authorities improve conditions in Pelican Bay’s special housing unit (SHU).

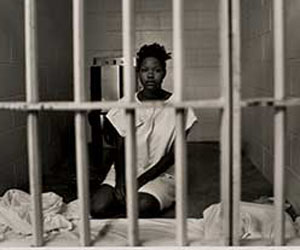

Built in 1989, Pelican Bay is the nation’s first supermax prison built for that purpose, and remains one of its most notorious. About a third of its roughly 3,100 inmates live in the X-shaped cluster of buildings known as the SHU. NPR’s Laura Sullivan, one of few reporters granted entry to Pelican Bay, described the unit in a 2006 report:

Everything is gray concrete: the bed, the walls, the unmovable stool. Everything except the combination stainless-steel sink and toilet. You can’t move more than eight feet in one direction…The cell is one of eight in a long hallway. From inside, you can’t see anyone or any of the other cells. This is where the inmate eats, sleeps and exists for 22 1/2 hours a day. He spends the other 1 1/2 hours alone in a small concrete yard…Twice a day, officers push plastic food trays through the small portals in the metal doors…

Those doors are solid metal, with little nickel-sized holes punched throughout. One inmate known as Wino is standing just behind the door of his cell. It’s difficult to make eye contact, because you can only see one eye at a time. “The only contact that you have with individuals is what they call a pinky shake,” he says, sticking his pinky through one of the little holes in the door. That’s the only personal contact Wino has had in six years.

When conditions at Pelican Bay were challenged in a 1995 lawsuit, the judge in the case found that life in the SHU “may press the outer borders of what most humans can psychologically tolerate,” while placing mentally ill or psychologically vulnerable people in such conditions “is the equivalent of putting an asthmatic in a place with little air to breathe.” Yet since that time, the number of inmates in the SHU has grown, and their sentences have lengthened from months to years to decades. Hugo Pinell, a former associate of George Jackson who is considered by some a political prisoner, has been in Pelican Bay’s SHU for more than 20 years.

Many residents of the SHU have been sent there on questionable grounds and have little hope of ever leaving. More than half of the men in solitary confinement in California are there because they have been “validated” as gang members and given indeterminate sentences. According to Corey Weinstein, a physician and prisoners’ rights advocate, the “single way offered to earn their way out of SHU is to tell departmental gang investigators everything they know about gang membership and activities, including describing crimes they have committed. The state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) calls it debriefing. The prisoners call it ‘snitch, parole, or die.’ ” Those, in other words, are the only ways out.

In April, prisoners in several corridors of the SHU announced their intention, on July 1, to “begin an indefinite hunger strike in order to draw attention to, and to peacefully protest, 25 years of torture via CDCR’s arbitrary, illegal, and progressively more punitive policies and practices.” The group of prisoners—which reform advocates say cuts across racial lines—issued five “core demands,” none of them particularly radical.

The strikers are asking that “individual accountability” replace “group punishments,” and they want an end to the debriefing program. They also called on the department to implement the recommendations of the US Commission on Safety and Abuse in Prisons, a bipartisan commission that issued a 2006 report on conditions in US prisons and jails. Among other things, it recommended that prisons make “segregation” from the general prison population “a last resort,” “end conditions of isolation” within the segregation units, and avoid long-term solitary confinement. The strikers also want the CDCR to provide “adequate food” and “constructive programming and privileges for indefinite SHU status inmates”—including one phone call per week, longer visiting hours, access to exercise equipment, art supplies, wall calendars, and more TV channels.

The state, however, seems already to have dug in its heels. “It’s appropriate for the CDCR to review the demands, but they’re not going to concede under these types of tactics,” spokeswoman Terry Thornton told California Watch. The prison will monitor their health, but “if an inmate decides he’s not going to eat, we can’t force him to eat.”