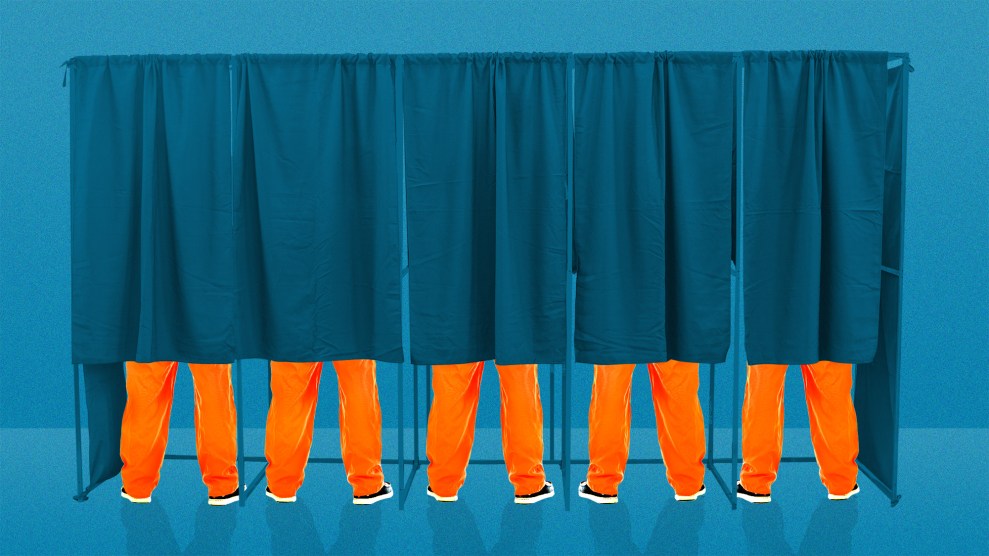

Mother Jones illustration; Getty Images

The voting rights of felons have been top of mind among criminal justice reformers for years. But that conversation has overlooked a group that, although technically eligible to vote, is often unable to cast a ballot: people who are awaiting trial in jail.

An Illinois bill that passed last month aims to change that. The bill, which the governor is expected to sign before the August 21 deadline, would require every Illinois jail—including Cook County Jail, the largest in the country—to make in-person or absentee voting available to pretrial detainees. The bill would also mandate that the state corrections department and jails give voter registration information to inmates eligible to vote upon release, including those with a past felony conviction. (Illinois is one of 15 states that restore felons’ right to vote after release.)

Under the proposed law, which is slated to be fully rolled out in 2020, Cook County Jail would become the first jail in the country to serve as an official polling place. The bill stipulates that in counties that have less than 3 million residents, which includes every county except for Cook, the jail will facilitate absentee voting. During the March primary election, inmates at Cook County Jail were able to cast their ballots in person in voting booths, and the jail is currently considering bringing voting machines to the jail for the November election.

“There is confusion around how election code actually applies to the jail,” says Jen Dean, who runs Cook County Jail Votes, the group that helps facilitate registration and voting in the jail. “[This bill] creates a system of uniformity across the state to make sure there are systems in place so that everybody has access to the ballot.”

Currently, only eight counties in the state, including Cook County, have any kind of process in place to ensure pretrial detainees can vote, according to a fact sheet released by the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois and the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law. This means that the thousands of other people awaiting trial in jail during an election might not get to vote at all, because state law doesn’t spell out a voting procedure for inmates and doesn’t require election authorities to report votes from jails, according to the Chicago Reporter. In the 2016 presidential election, the Chicago Reporter notes, only 23 of the state’s 109 election authorities reported votes cast in jail.

Prior to the beginning of Cook County Jail’s program last fall, the jail received voter registration packets for absentee voting for interested inmates to fill out, according to a sheriff’s office spokeswoman. There were also some independent voter registration efforts, Dean said. Now, there are regular voter registration drives and civic education initiatives. The program was set up by Chicago Votes, one of the groups backing the bill, and although it began before the bill was introduced, it is serving as a sort of test case for how the bill will be implemented.

But even in jails that ensure inmates can vote, turnout is exceptionally low, according to data obtained by Mother Jones. Take DuPage County, the second-most-populous county in the state: In the 2016 presidential election, only two inmates voted out of an inmate population of 625—less than 0.33 percent, according to the county sheriff’s office.

Other jails with voting programs have only slightly better numbers: The average turnout rate of the eight jails that had a voting process during the 2016 presidential election and the March 2018 primary was 13 percent. Cook County had the highest turnout by far—about 19 percent of inmates voted in the presidential election and 10 percent voted in the primary. Without Cook County, the numbers drop drastically—there was only a 4 percent turnout among the remaining seven jails in 2016 and 2018. Of course, there are limitations to these numbers: Not every inmate in the jail is eligible to vote, and some are not awaiting trial, although pretrial detainees account for more than 90 percent of Illinois’ jail population.

According to Dean, pretrial inmate turnout is low not because people don’t want to vote, but because there’s so much confusion surrounding the process. Even getting ballots distributed to inmates can be an obstacle. The bill’s advocates are hopeful that a system that includes voting machines that streamline the process for jail authorities and clear instructions on absentee voting for inmates will ease the process and get more people to cast ballots. Often, Dean says, turnout comes down to how much corrections officers understand the system.

Furthermore, the bill’s supporters hope turnout will increase even in jails where voting is already possible. In Cook County Jail, for example, which has had a system to allow absentee voting in place for years, Dean said her group hopes to increase participation to 50 percent of eligible voters in the upcoming November election.

Not everyone is convinced the bill will do much. Nancy Griffin, a program coordinator for the Champaign County Sheriff’s Office who helps with the county jail’s voting program, says that no matter how aggressively jail authorities promote the voting program, low turnout boils down to inmate apathy. Champaign County, which instituted a voting program in its jail in 2012, had an inmate voter turnout of a little over 4 percent in the 2016 presidential election, and less than 1 percent in the 2018 primary.

So how many people could vote from Illinois jails this fall? There are about 21,000 people in jail in Illinois, according to a 2016 report from the Prison Policy Initiative. Outside Cook County Jail, which is an outlier due to its size, there are still 15,000 inmates in smaller jails throughout the state. Taking into account that not all inmates are eligible to vote, and assuming turnout rate is 4 percent—the same as the seven counties that already have voting systems—there will likely be less than 600 new voters, in addition to those in Cook County.

That number might seem inconsequential compared to the 5.6 million people who voted in the 2016 presidential election in Illinois. Nonetheless, advocates say the bill should not be dismissed. Myrna Pérez, director of the Voting Rights and Elections project at the Brennan Center for Justice, pointed out that disenfranchisement affects the next generation of voters, not just those in jail who can’t vote.

“It’s a mistake to assume that just because something isn’t going to have the kind of turnout or impact now that it’s not a good habit to keep perpetuating,” she told Mother Jones. “[Voting] is a fundamental right.”

Dean says her organization is currently in communication with states and cities that want to implement similar programs, including Las Vegas, New York City, and Texas. Already, jails in cities including Baltimore, Cleveland, and Los Angeles have all implemented voting programs. Last year, inmates at an Indiana jail sued the county sheriff for not allowing them to vote while they were awaiting trial. In Vermont and Maine, voting is available to everyone, including prisoners, which begs the question: What would it mean for elections if every jail in the country had a voting program? The short answer: not much. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, there are approximately 465,000 pretrial detainees in the United States. Based on what we’ve seen in Illinois, it’s unlikely widespread enfranchisement of pretrial detainees will have much of an impact on the political landscape.