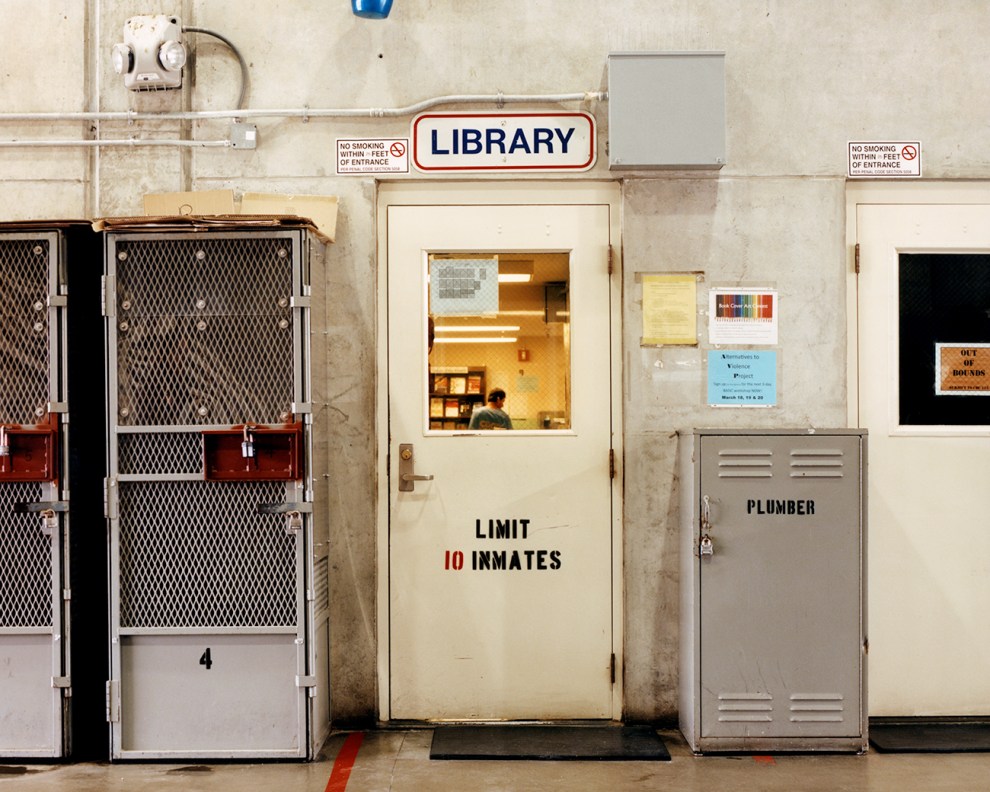

Behind the walls of California State Prison, Sacramento, six inmates gather in the library for their weekly short-story club. The librarian introduces the day’s pick, Doris Lessing’s A Sunrise on the Veld, and the men take turns reading it aloud. Some of them lean forward in their chairs as they listen; one traces the words with his index finger. It almost feels like a classroom, except that the library’s computers don’t connect to the internet, and there’s no natural light. A back room holds metal cages where prisoners with behavioral problems can do legal research. About half the books are donated, many from a public library, and the pickings are slim: Nonfiction is kept behind the counter, and most of the fiction is locked away in a small room.

About half the books that make up the library collection at California State Prison, Sacramento, are donated.

Andrea Hubbard is the senior librarian at California State Prison, Sacramento, Facility B.

But for Michael Blanco, who is 19 years into an 87-to-life sentence, this represents a vast improvement. At his last prison, he says the librarians stocked the shelves largely with books inmates had requested from family and nonprofits. Still, California has one of the better prison library programs. The state spends $350,000 annually on recreational books for prisoners, much more than other states do.

Citing concerns about contraband, officials around the country are ratcheting up restrictions on what gets into prison libraries. They say there’s been an uptick of drug smuggling via books, whose pages can be soaked with synthetic marijuana or other potent liquids. In September 2018, Pennsylvania’s corrections department temporarily banned all book donations after dozens of prison staffers landed in the emergency room with tingling skin, headaches, and dizziness after handling inmates’ belongings. New York, Maryland, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons have adopted similar policies, and Washington state banned most used books from its prisons, though all eventually backtracked because of public outrage.

Even in places without wholesale bans, corrections departments are cracking down. Florida blocks 20,000 titles and Texas blocks 10,000 titles they claim could stir up disorder. A recent report by PEN America decried similar restrictions around the country as so arbitrary and sweeping as to effectively be “the nation’s largest book ban.” Texas prisons have prohibited Where’s Waldo? and a collection of Shakespeare’s sonnets with racy illustrations. Literary groups and activists banded together to protest the censorship in Florida prisons by appealing to the Supreme Court in the fall of 2018. “Access to compelling books can be a godsend,” they wrote in an amicus brief, “for both prisoners and the rest of us, who benefit when prisoners have constructive outlets and better odds of rehabilitation.”

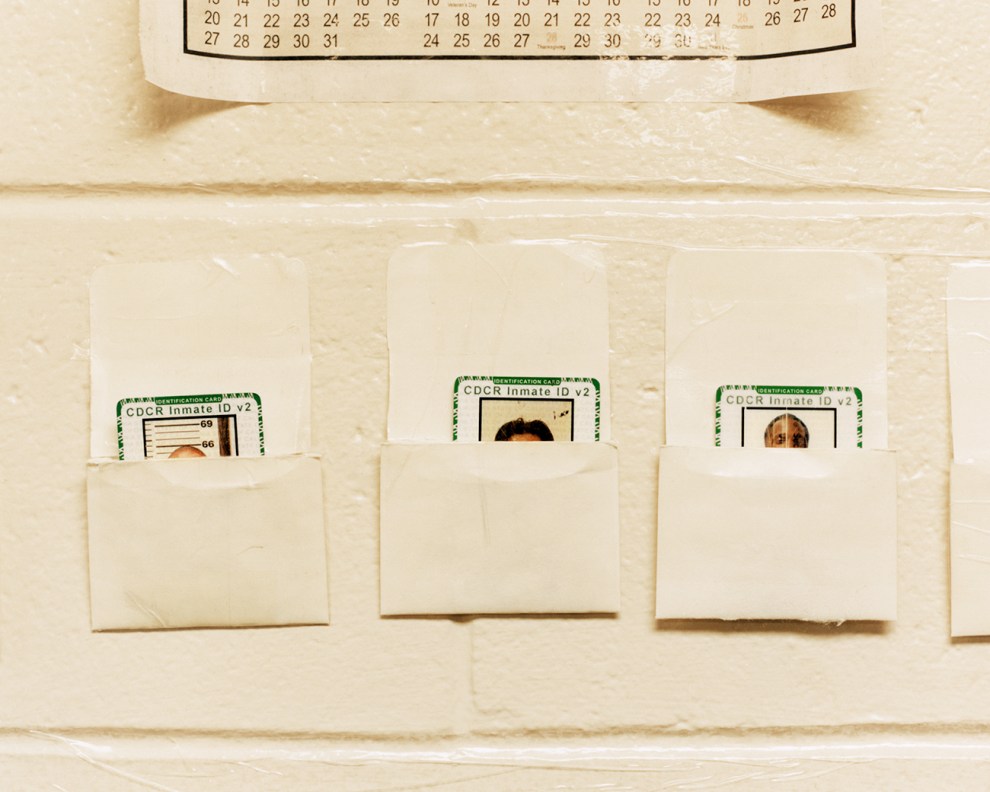

Inmates must have their state-issued IDs to get into the library.

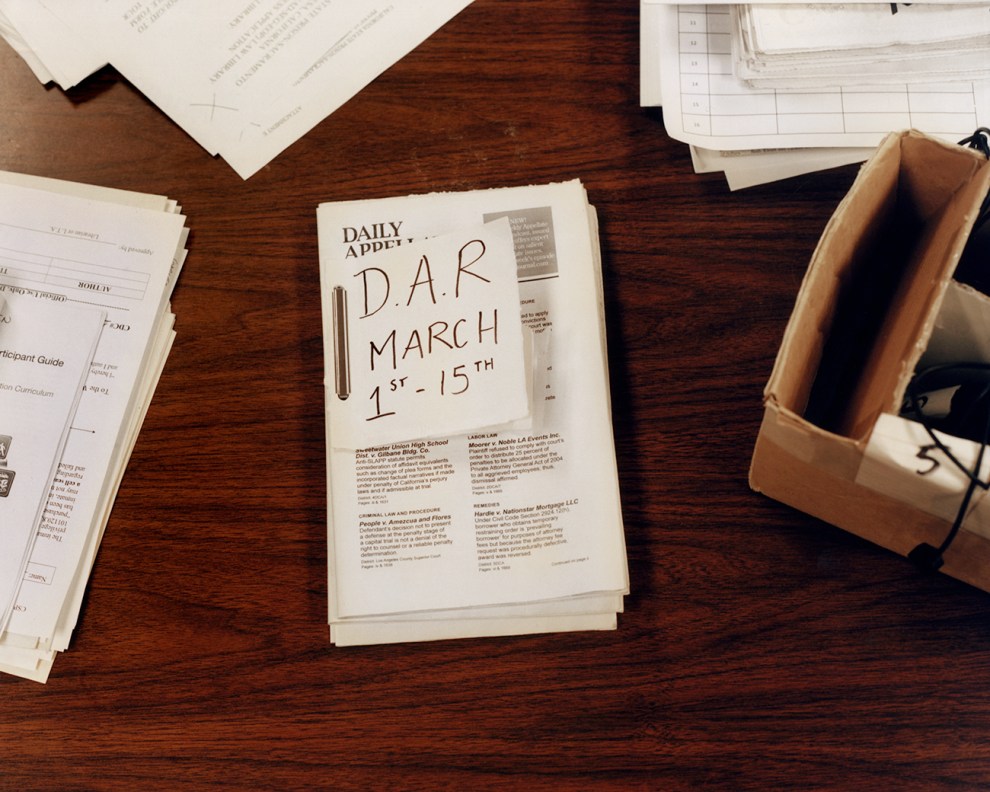

Legal texts help people conduct research for their cases.

The library chairs are hard and not ideal for lounging. Inmates who check out books often read in their cells.

A small window connects the main room of the library with a back room.

For centuries, the printed word has been seen as a way to help incarcerated people turn their lives around. In the late 1700s, inmates received religious texts to encourage their rehabilitation. In the 1940s, California prison librarian Herman Spector pushed the theory of bibliotherapy, which held that incarcerated people could be reformed through reading. During a talk to the American Prison Association in 1940, Dr. C.V. Morrison recommended book “prescriptions” for inmates; around that time, officials at California’s San Quentin Prison took library records into account when deciding parole eligibility.

Some lockups in Brazil and Italy allow people to shave three or four days off their sentences for each book they finish. A 2014 study by psychologists in the United States found that bibliotherapy in jails and prisons helped reduce inmates’ depression and psychological distress.

When Glennor Shirley first started working as a librarian in a Maryland prison in 1986, it held little more than boxes of encyclopedias and magazines scattered around the room. She soon ordered texts about job training and parenting, novels, and even children’s books so that inmates could read to their kids. Vince Greco, a formerly incarcerated man who spent time in her library, called it “the only freedom” he had. And prison officials were happy, too, says Shirley, who later oversaw all prison libraries in the state; they told her that inmates with access to good library services were less likely to file lawsuits about prison conditions.

In the back room, people with behavioral problems must conduct legal research in locked cages.

But after two and a half decades, Shirley resigned in 2011 because of funding cuts: During the recession, Maryland’s budget for prison library books dwindled from about $200,000 a year to almost nothing, she says. Librarians still had money for legal texts, which are required in prisons, but they could no longer afford novels or other recreational books. (The state Department of Labor says its total budget for prison libraries in 2011 was about $94,000, but it could not provide a breakdown of how much money was allocated for new books.)

Today, another prison librarian in the state, who asked not to be named, notes that large facilities get about $1,000 a year for recreational books; some small facilities get less. His department is “treated like an ugly step-child,” he says. Illinois, meanwhile, spent $276 on nonlegal books across 28 correctional facilities in 2017, compared with about $750,000 annually during the early 2000s, according to an investigation by Illinois Newsroom.

Until recently, librarians in that state were one of the lowest-paid employees in each prison, says Barbara Kessel, who volunteers with a local program called 3Rs, short for Reading Reduces Recidivism. Under a new Democratic governor, they got a raise. The corrections department says it allocated $75,000 for new library books this year.

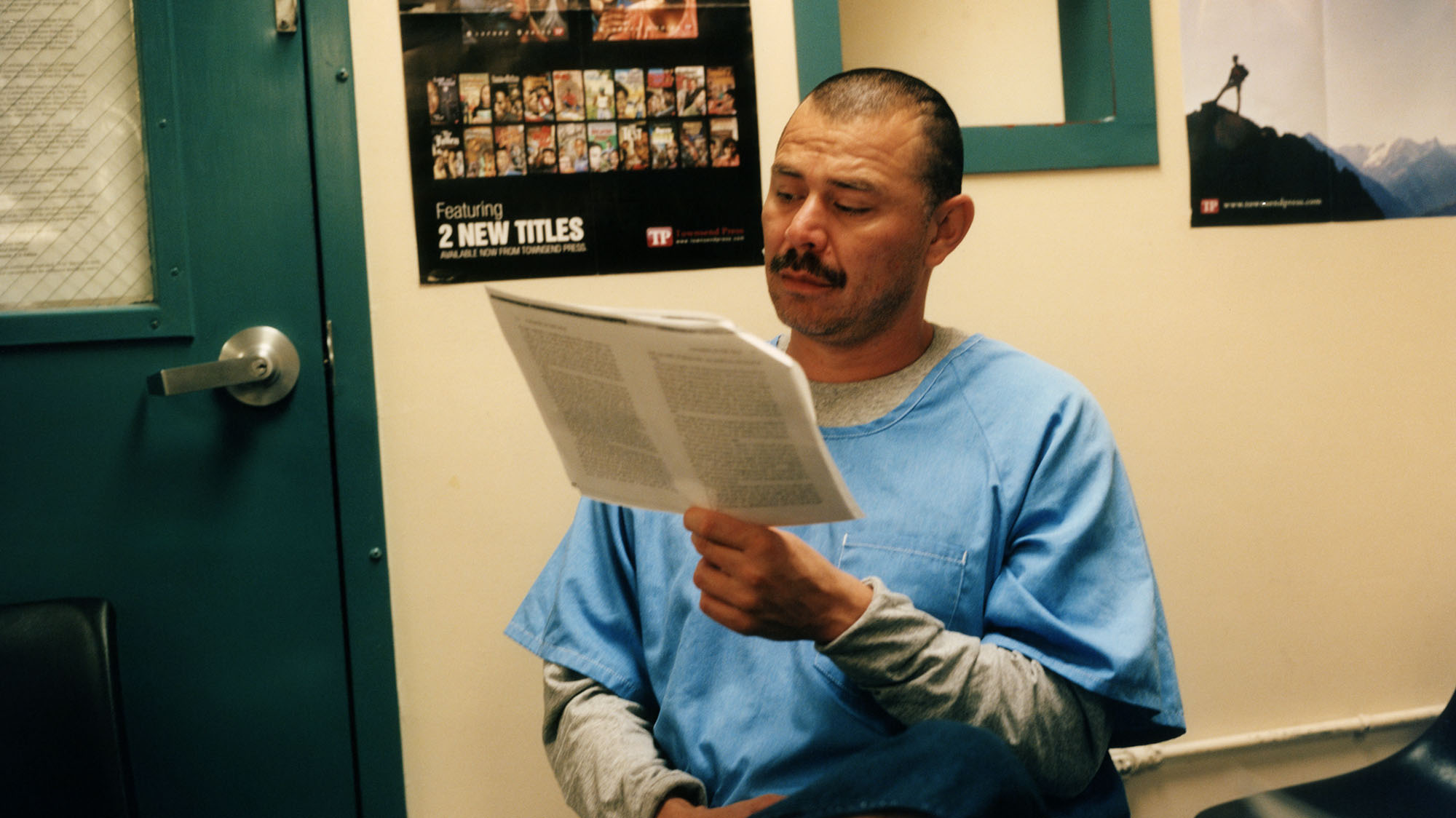

Michael Blanco, serving an 87-to-life sentence, talks with a library clerk.

In budget-strapped prisons, inmates are increasingly writing to volunteer groups that send them free books. The Prisoners Literature Project got about five to 10 letters a month when it started in the 1980s; today it receives thousands from around the country. The most common request is for dictionaries. They’re in such high demand, Kessel says, “some people were collecting [them] for contraband, so they could trade them for things.”

On a Sunday afternoon, PLP volunteers in Berkeley, California, fielded requests from inmates looking for everything from true crime to math books. Others wanted the last two installations of the Harry Potter series, a French dictionary, Marvel Comics, or Stephen King. Jasmine Markovich, a high school student who started volunteering after reading Just Mercy, a book about a wrongfully convicted man on death row, prepared a package for an inmate requesting thrillers. “Stay strong,” she wrote in a note, signing it with a heart.

But many of these books never reach their intended recipients. For security reasons, facilities have rules about what makes it in. Most prisons prohibit hardcovers, since they can conceal knives or other contraband. Books about sex, racism, violence, and gambling are often off limits. “Do NOT send The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo series,” reads a note to volunteers about a prison in Wasco, California. A facility in Florida rejects “how to” books.

These restrictions are “hopelessly inconsistent,” the Prisoners Literature Project and other book donation groups wrote to the Supreme Court last year, urging it to reverse a Florida corrections department ban on the magazine Prison Legal News. For instance, a Virginia prison once blocked inmates from reading Ulysses, “widely considered to be one of the finest English-language novels ever written,” the groups wrote in their amicus brief. Texts that are critical of the criminal justice system are sometimes targeted: Florida, among other states, has censored Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, which highlights how African Americans are disproportionately punished by law enforcement. A memo obtained by the New York Times said the book had been banned because it was a security threat and had “racial overtures.”

Inmates at California State Prison, Sacramento, gather for a weekly short-story club in one of the facility’s libraries.

To avoid the problems that crop up with paper, some departments encourage prisoners to read on tablets, which are now available in at least some prisons in more than 30 states. Pennsylvania inmates can choose from more than 8,500 e-books through the vendor GTL, but they come at a hefty price: Tablets cost nearly $150 and some e-books—many of which can be downloaded for free outside of prison—cost as much as $24.99. Popular titles like The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl aren’t always available, though inmates can download Diary of a Mistress for $14.99 or Diary of an Alcoholic Housewife for $20.99. “That is not a library,” says Kessel. In West Virginia, inmates receive tablets at no cost but are charged three cents a minute to read on them, even when the books would otherwise be free online.

Kessel says she can understand why literature might not be a top priority in prisons. In states where prison budgets are already stretched thin, she concedes, “books are not their biggest problem.” But skimping on reading doesn’t make sense if the goal is to help people stay out of trouble later. In 1991, a professor and a judge in Massachusetts launched a program that diverted offenders from prison if they completed a reading and discussion course on a college campus; an early study of the initiative, which expanded to parts of Texas, New York, and other states, found that by mid-1993 just 18 percent of participants were convicted of another crime, compared with 45 percent of a control group.

Toward the end of the short-story discussion in Sacramento, the men return to a moment in the story when its protagonist, a young boy, comes across a wounded buck and feels powerless because he can’t stop it from dying. The librarian asks whether the inmates can relate—whether there’s anything they’d like to have more control over. The doors, someone says. Another wishes his cell had a window that would open, so he could breathe the fresh air. “I don’t like people going through my personal property,” adds a third.

A bald inmate with dark eyebrows says he’d rather focus on what they can change, not what’s out of their control. But “you can’t change that the windows don’t open,” someone counters. “You can,” he tells them. “Write about it.”