At first, Pamela Lopez did not intend to name names. After more than a decade as a lobbyist in Sacramento, California, representing school districts, Native American tribes, and cannabis companies, Lopez had learned how to put up with a lot of crap from men—the dudes who took credit for her ideas, the official who insisted she wear open-toed shoes to lunch, and the boss who laughed off her complaints. “I had to make my peace with recognizing that if I wanted to be a significant actor in politics, and work in the political world, that putting up with abusive behavior, putting up with sexism and sexual harassment by some men, was just part of the cost of doing business,” she says.

Then, at a party in January 2016, a state Assembly member allegedly pushed her into a bathroom, masturbated in front of her, and urged her to touch him. She told a few close confidants about the incident—her now-husband as well as her business partner and a friend—but otherwise she kept it to herself. “I was afraid that if I offended a lawmaker, that that lawmaker might refuse to meet with my clients, or refuse to vote on bills or issues that were of importance to my clients,” Lopez explains. The lawmaker who accosted her, she says, “was a very powerful legislator. Who knew?”

In the fall of 2017, the MeToo movement swept through Hollywood and into newsrooms, boardrooms, and statehouses. Lopez signed an open letter from women in California politics calling out the “pervasive” culture of “dehumanizing behavior by men” in the capital. Explaining why they hadn’t spoken up earlier, they wrote, “We don’t want to jeopardize our future, make waves, or be labeled ‘crazy,’ ‘troublemaker,’ or ‘asking for it.’” When a New York Times journalist contacted the signers, Lopez agreed to tell her story about the Assembly member but did not identify him.

Her allegations hit Sacramento like a tidal wave. Democratic lawmakers called a hearing and urged Lopez to make a formal complaint. On December 4, 2017, she submitted a report to the Assembly rules committee and held a press conference with Jessica Yas Barker, who allegedly had been sexually harassed at work by the same man years earlier. Together, they named him: Matt Dababneh, a 36-year-old Democrat from the Los Angeles suburbs, the chair of the Assembly banking committee, and a hotshot on the party’s moderate flank.

Within days, three more women told a Los Angeles Times reporter that Dababneh had sexually assaulted or harassed them. One accused him of sexual assault; another said he frequently talked about sex in front of her at work. The third, like Lopez, alleged that Dababneh had exposed himself to her and asked her to touch him while they were working for John Kerry’s 2004 presidential campaign.

Though Dababneh denied all the allegations, he announced his resignation a few days after Lopez named him. He pledged to cooperate with an investigation by the Assembly rules committee, which he said would bring to light “significant and persuasive evidence” of his innocence. Yet the outside investigator hired by the legislature who interviewed 53 people over seven months found that Lopez’s story was “more likely than not” accurate. Dababneh’s appeal to the heads of the rules committee was rejected.

Fifteen members of the state legislature were accused of sexual misconduct in 2017 and 2018. In November 2018, the state’s Democratic Party chair resigned following accusations of inappropriate behavior. As more revelations came to light, Lopez received support from survivors and allies as well as clients, and she founded an organization to combat sexual harassment.

But Dababneh wasn’t ready to move on. In August 2018, he sued Lopez for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. He said she had fabricated her story, and he asserted that he had suffered “anguish, fright, horror, nervousness, grief, anxiety, worry, shock, humiliation, and depression” as a result. He also demanded unspecified damages.

“I want my reputation back,” Dababneh, who is currently unemployed, tells me. “I would like to start a new career path. And I want to also make an example that you cannot just lie about someone, and ruin their career, and ruin their life, and have no consequences.” All of his accusers, he claims, were either motivated by self-interest or manipulated into making false allegations by political operatives trying to take him down. As for Lopez, he says, “All I can tell you is that it seems like she enjoyed her 15 minutes of fame.”

As more survivors have come forward to call out perpetrators of sexual assault and harassment, a legal backlash to the MeToo movement has been brewing. While it’s well known that powerful men have preemptively quashed accusations with payoffs and nondisclosure agreements, less well known is that dozens of men who claim they are victims of false allegations have sued their accusers for speaking out publicly. The plaintiffs include celebrities and college students, professional athletes, professors, and politicians. At least 100 defamation lawsuits have been filed against accusers since 2014, according to Mother Jones’ review of news reports and court documents. Prior to October 2017, when the MeToo hashtag went viral, almost three in four claims were brought by male college students and faculty accused of sexual misconduct; they usually sued their schools as well as their accusers. Since MeToo took off, cases have been filed at a faster rate, with three in four coming from nonstudents.

This list of cases is not comprehensive, but attorneys confirm that these suits are becoming more common. The Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund, which helps workplace harassment victims pay their legal bills, has assisted 33 accusers, including Lopez, who have been sued for defamation in the past two years—nearly 20 percent of its caseload. As the number of cases grows, so does the chilling effect: Defamation lawsuits are being used “more and more to try to silence people from coming forward,” says Sharyn Tejani, director of Time’s Up. “It was not something that we expected would take as much of our time and money as it has.”

Bruce Johnson, a Seattle lawyer who specializes in First Amendment cases, says that before fall 2017, he was contacted twice a year by women who were worried about being sued if they spoke out about sexual violence or harassment or who were threatened with legal retribution for doing so. Now it’s every two weeks, he says. Alexandra Tracy-Ramirez, a lawyer who represents both survivors and accused perpetrators in campus-related cases in Colorado and Arizona, has also noticed more accusers speaking out and facing the prospect of being sued.

Public figures must clear a high bar to win a defamation lawsuit. Yet dozens of prominent men—including Johnny Depp, Nelly, and Drake—have pursued lawsuits claiming their reputations were harmed by accusations of sexual misconduct or domestic violence. Other plaintiffs include former Pittsburgh Steeler Antonio Brown, former casino magnate and Republican National Committee finance chair Steve Wynn, former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore, and Democratic Pennsylvania state Sen. Daylin Leach. The music producer Dr. Luke is suing the singer Kesha for alleging that he sexually assaulted her; a judge recently ruled that he is not a public figure and she had defamed him in a text sent to Lady Gaga.

Not all men pursuing defamation suits are boldface names. Last year, an Iowa man who had been charged with sexually assaulting a woman in South Carolina sued her for defamation. She countersued, claiming his lawsuit was an “effort to intimidate and humiliate [her] to gain an advantage” in his criminal trial. A similar battle is playing out in Alabama, where a judge dropped charges against a male massage therapist accused of criminally harassing a female client. When she brought a civil suit alleging sexual assault, he countersued, claiming defamation.

It’s not just alleged victims who are getting sued: Defamation lawsuits are also hitting people who have amplified sexual misconduct allegations online. In a widely covered case, author Stephen Elliott sued journalist Moira Donegan, who created a crowdsourced spreadsheet of “shitty media men” in 2017 that included an entry about him. Similar documents shared among models and cartoonists have also sparked suits. In November 2017, a New York burlesque producer named Joseph Naftali (known professionally as “Joe the Shark”) sued a performer, Bunny Buxom, who had said that he sexually assaulted her, as well as two other people who had made Facebook posts about her allegation. Those two settled, but Buxom is still fighting the lawsuit.

And then there are the accusers who turn to defamation suits to pursue their alleged abusers, often years after the statutes of limitations have run out on possible criminal charges. Summer Zervos, a former contestant on The Apprentice, is suing President Donald Trump for tweeting that claims of sexual assault against him, including her own allegations that he kissed and groped her without consent in 2007, were “100% fabricated and made up.” E. Jean Carroll, an Elle columnist who publicly accused Trump of rape last June, filed a defamation suit against the president in November. Trump had tried to wave off her allegations by dismissing her as “not my type.”

Few of these cases go to trial—most are dismissed, settled, or dropped. But their impact extends well beyond the courtroom. According to Tejani of Time’s Up , the threat of being sued, and the expense of mounting a legal defense, has deterred many survivors who seek to speak out—not to mention the stress of rehashing traumatic events in court. Anita Yandle, a former lobbyist who was one of eight women to accuse a Washington state lawmaker of harassment in 2018, says about a dozen more women never came forward, in part because of rumors that he was considering a defamation suit. Alyssa Leader, a former victim advocate and rape crisis counselor who is now studying to become a lawyer for survivors, recalls a client who wanted to file a restraining order against her abuser but hesitated because he had money and was well connected. Her clients, she says, “definitely were wondering, ‘Could my abuser get me in trouble? Could they file a lawsuit against me?’”

After Lopez spoke out, her lawyer, Jean Hyams, started getting calls from more women who wanted to go public about other cases. “They just wanted to break their silence,” Hyams says. One of the first things she told them to consider was whether they might be sued. Part of the calculation was whether their abusers’ affluence and power made them more likely to turn to the courts. “The whole conversation is about how you do this in a way that poses the least risk to you, but allows you to have this kind of agency,” Hyams says. “To not continue to be under the control of this person who perpetrated, by keeping their secrets for them.”

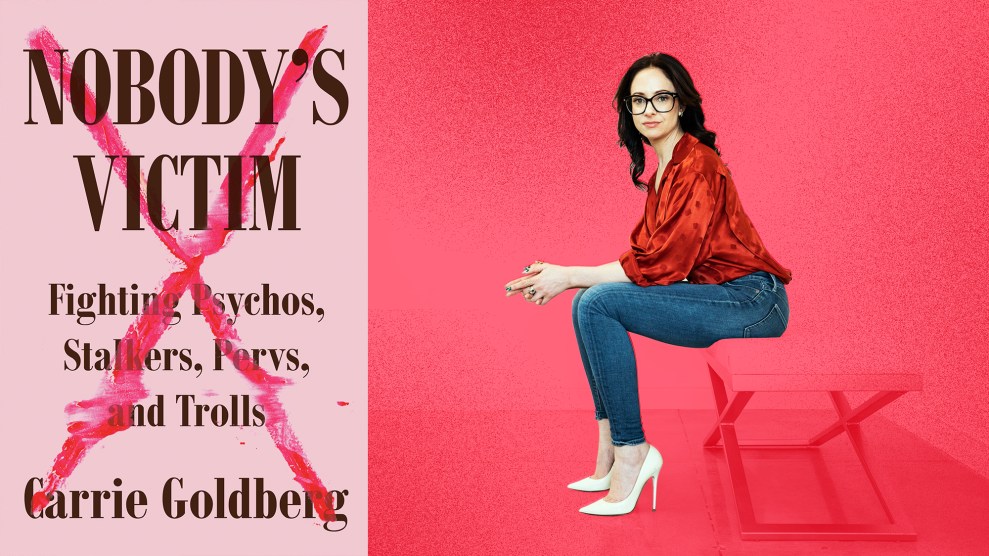

Carrie Goldberg, a New York City litigator who represents victims of revenge porn, stalking, and sexual violence, says that defamation defense has recently become a major part of her practice. Her firm has represented 15 accusers facing defamation claims in the last year. “Our clients are exposing predators, and then get sued,” Goldberg says. “It’s such a beautiful moment right now, where victims are finding their voice, and finding a community. It’s heartbreaking that they then are met with litigation and retaliation.”

“But on the other hand,” she adds, “it’s important for people to know the risks if they come forward.”

Pamela Lopez is one of five women who have accused Matt Dababneh of sexual misconduct.

Brinson + Banks

Dababneh says he learned that Lopez was planning to name him from a mutual friend who threw the coed bachelor party where she said she was assaulted. He had read about her in the New York Times, yet at first he didn’t recognize her name. (She had recently changed her last name.) He thought her story sounded “awful” and wondered why she didn’t report the incident.

After learning that she had accused him, Dababneh contacted other people who had been at the party, questioning them about Lopez’s behavior that night. He also asked if they could back up his side of the story: He’d spent the night “joined at the hip” with two friends, and the party was so busy that if he had followed Lopez into the bathroom, someone would have seen it. He hired a law firm headed by Patricia Glaser, who represented Harvey Weinstein when he sued the Weinstein Company after it fired him amid allegations of decades of sexual harassment and assault. When Dababneh learned about the press conference Lopez had scheduled, Glaser sent her a cease-and-desist letter threatening to hold her “fully accountable in damages.”

Lopez went ahead anyway. Immediately afterward, Dababneh says, the Assembly’s Democratic leadership pressured him to step down. He only did so once they assured him that an independent investigation would give him a chance to clear his name. Over the next seven months, he met for two interviews with the Assembly’s investigator and submitted evidence that he says supports his version of events, including a cheerful thank-you email Lopez sent the party’s organizers after the weekend. “How do you disprove a negative? It’s very difficult,” Dababneh says. He also pointed out that the Times reported that the incident happened at a Sacramento bar, not a Las Vegas hotel. Lopez says she did not correct the reporter at the time because she was afraid it would lead to Dababneh being identified. (She told the Los Angeles Times that she had “purposely misstated” the location to obscure his identity.)

The day Dababneh learned about the finding that Lopez’s allegation was “substantiated,” he decided to follow through on his threat to sue her. “Maybe I’m stubborn and maybe I have this unreasonable sense of fairness, this idea that people that lie shouldn’t get away with it,” he says. He chose not to sue his other accusers (though he is not ruling it out), he says, because he believes their stories were less damaging than Lopez’s—and because he couldn’t afford to.

Dababneh also sued the Assembly, trying to force it to void its finding that he violated its sexual harassment policy and to release more details from its investigative report. (The chief administrator of the Assembly rules committee told Dababneh that the report is subject to attorney-client privilege.) Dababneh claims the inquiry’s conclusions were unsupported and that it was fundamentally unfair, in part because he has not been shown all the evidence against him or given a chance to question witnesses, specifically Lopez. “This is how Saudi Arabia and third-rate dictatorships do investigations—closed door, behind the scenes,” Dababneh says. “No due process, no cross-examination, no transparency, no fact-finding or evidence. None of the things that make all of Western law—going back to the Magna Carta and through the Constitution and into the civil rights era—meaningful.”

When Lopez first read Dababneh’s complaint, she recalls during an interview with Hyams present, questions raced through her mind: She’d recently had a baby and was trying to buy a house—could she afford a protracted legal battle? Was she still safe in Sacramento? “I remember that sensation when something scary or bad is happening, similar to a car accident, where it feels like time slows down.”

Dababneh says the suits are the only way he can reclaim his reputation and rebuild his life. According to public records, he has paid at least $430,000 to Glaser’s firm using campaign funds channeled through the Matt Dababneh for Lieutenant Governor 2022 political action committee. “I’m ruined,” he says. “I’ve lost my career, I’ve lost my financial stability. I can’t provide for my family anymore. I’m selling my house to pay my debt and legal fees. I’ve literally applied for hundreds of jobs and the one time I got an interview, when they realized my situation they never called me back.”

In theory, defamation cases are about the truth: To prevail, plaintiffs must convince a judge or jury that the defendant knowingly made false allegations against them. Given the widespread failures of police, criminal courts, university administrators, and other official channels to provide accountability, perhaps it’s not surprising that defamation lawsuits have become another venue for adjudicating the facts. “That’s what these offenders don’t quite get,” says Goldberg, who sees her defamation defense cases as an opportunity to prove her clients are telling the truth. “We’re basically relitigating the sexual assault.”

That’s exactly what the accused men say they’re after. The legal complaint by Naftali, the burlesque producer, states that it was filed “with full knowledge that truth is a defense to a defamation claim.” Dababneh says he wants all the evidence from the Assembly investigation made public because he believes it will exonerate him. This result isn’t unheard of: Last August, a Georgia policeman was awarded more than $131,000 after winning a suit against a woman who said he’d sexually assaulted her at a traffic stop. In 2017, a jury awarded a former Army colonel $8.4 million from a blogger who said he had raped her at West Point in the 1980s.

Yet defamation lawsuits are often used by wealthy and powerful people to punish their critics. These frivolous cases, known as SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation), are designed to prevent people from speaking out about matters of public interest. It’s such a widespread strategy that 30 states have anti-SLAPP laws that protect defendants from these punitive suits by providing a mechanism to get them tossed before they go too far.

SLAPP suits also fit into a common defense against accusations of sexual misconduct: deny, attack, and reverse victim and offender. This kind of response, known as DARVO, involves questioning an accuser’s credibility while recasting the accused as the true victim. It’s been used for decades by criminal defense attorneys who slut-shame rape survivors and was employed by Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh during his confirmation hearings. Frivolous defamation lawsuits are another example of recasting the alleged offender as victim, explains Jennifer Freyd, the University of Oregon psychology professor who originated DARVO theory. There’s some empirical evidence to suggest it works. A study conducted by Freyd and a graduate student, currently under review, asked 316 college students to read a description of violence between dating partners as well as the victim’s and perpetrator’s accounts of what happened. If the aggressor used deny, attack, and reverse tactics when presenting their side, students found both parties less credible yet were more likely to blame the victim.

“The fact that somebody responds really aggressively, including with a DARVO response, is not a proof of guilt,” Freyd warns. But even when the accused is innocent, she says, aggressive reactions are damaging to all involved because they shut down discussion or the possibility of coming to a resolution. “It does harm. And furthermore, it’s not necessary.”

In a legal filing, Dababneh claims that Lopez used cocaine at the party where he allegedly harassed her. (“My response to any of Dababneh’s accusations is no response, because this is about what he did to me,” Lopez says.) During a phone interview with his PR consultant, Elana Weiss, on the line, Dababneh says he would settle with Lopez “if she publicly stated that she lied, that this did not occur, that I am innocent of this, and that she apologized to me.” He adds, “I wouldn’t even ask for a dollar if she would publicly state that she made this up or that she was mentally ill and somehow was manipulated into this. Look, I’m not a lawyer and I can’t say what the exact language would be—”

“Let’s be careful there. Wait, back up,” Weiss breaks in.

“Yeah, I’ll back up—”

“Back up,” she repeats, laughing. “Yeah, I think what he was saying was, you’ll take a settlement as an apology, and you don’t want a single dollar. A public apology, period. Why don’t you say that?”

“That’s what I’ll say,” Dababneh says.

After he came to Sacramento, rumors about Dababneh’s treatment of women had circulated in its gossipy political community. He says they were “spread by colleagues who didn’t like me or were jealous of me.” In June, a lengthy article on the site RealClearInvestigations titled “Sex Predator or #MeToo Prey?” laid out Dababneh’s case for his innocence, including his belief that his downfall was orchestrated by his political enemies. Dababneh says media coverage of his claims, especially that article, “made people take a second look” at his lawsuit.

Indeed, for plaintiffs, just filing a defamation suit can be a useful step toward repairing their reputations. “There’s the expectation that if you’re falsely accused of something, you’re not going to stand there and silently allow people to say things about you,” says Tracy-Ramirez. She cites a defamation lawsuit she filed for a client who claimed they had been falsely accused of pedophilia: “That’s the kind of case where the accusation itself is so immediately damaging, that there’s really not a lot of options for you to get a narrative out there, to say, ‘Wait a minute. I did not do this.’”

But it’s a gamble. Alex Berke, an employment lawyer in New York, says she asks men what their goal is when they come to her after being accused of sexual harassment. Will a lawsuit really stop people from talking about them? Goldberg says suing accusers can backfire. “There’s this false belief by people accused that ‘Hey, if I go through the trouble and expense and time and publicity for a defamation lawsuit, then it surely will show the world that I’m innocent of this wicked allegation.’ That’s just not true,” she says. “If anything, it shows that they have that kind of aggressive temperament that reinforces the original allegation in the first place.”

Defamation lawsuits can serve other purposes for the accused. Eric Rosenberg, an Ohio attorney who has represented students accused of sexual assault or harassment since 2011, typically sues schools for allegedly violating his clients’ right to due process or discriminating against them as men. But in more than 10 cases, he’s also gone after accusers for defamation. The goal of these suits, Rosenberg says, is not to publicly discredit the accusers but rather to compel them to write a letter retracting their allegations, which his clients can include in academic or professional applications. “These lawsuits have gotten them into dental school, law school, they would never otherwise gotten into,” he says. “My goal is to help these students reclaim their lives after a false allegation.”

In 2018, California passed a law protecting employees from being sued for defamation for reporting sexual harassment to their employers. The same year, in response to reports of male college students suing women who accused them of sexual misconduct, Louisiana enacted a law allowing defamation lawsuits against accusers to be frozen until all related criminal, civil, or administrative hearings are “complete and final.” The law prohibits plaintiffs from keeping any material related to those investigations secret and allows damages to be awarded to the defendant if the lawsuit is found to be frivolous. “Part of the whole purpose of sexually assaulting someone is to exert power over them,” says J.P. Morrell, the Louisiana state senator who sponsored the legislation to prevent accusers from being preemptively sued. “While these women were trying to have their day in court, [the plaintiffs] were reasserting their power through their means, to basically threaten to bankrupt college students with expensive litigation.”

But such specific protections for accusers are uncommon. In the absence of anti-SLAPP protections, particularly in federal court, survivors may feel coerced into settling to avoid a painful legal battle. Leader, the law student training to fight such cases, points out that groups that provide legal aid to survivors are rarely equipped to take on the demands of defamation suits. And a federal grant program for organizations that represent survivors prohibits the funding from being used for tort cases, including defamation.

Last year, a superior court judge in Sacramento ruled that Lopez is partially protected by California’s strong anti-SLAPP law. The judge found that her report to the legislature about Dababneh was legally protected and that she could not be sued for what she said in it—but the press conference she gave afterward was fair game. Lopez is appealing that ruling, asking that the entire case be thrown out. Her lawyers argue that Dababneh’s lawsuit is meant as retaliation—“a message that the women he has sexually harassed would be punished if they dared speak out.” According to Hyams, if the case is allowed to proceed, Lopez’s legal team could call Dababneh’s other accusers to testify. Despite the chance that she too could be sued, Jessica Yas Barker says, “I’m not changing the way I talk about anything…because nothing that I say about it has changed and it’s all true.” Lopez also says she will not recant: “I’m not going to make up any story just to get out of being legally intimidated.”

She is trying to keep her chin up while the case unfolds. “I do my best to project some wherewithal and some courage,” she says. “I want other survivors of sexual assault to see that you can do this and you can get through this.” She doesn’t regret speaking out, doesn’t regret naming Dababneh. But being sued, she admits, “scares the shit out of me all the time.”

“Yeah, I got to be in the press a little bit—for 15 minutes of fame, so to speak. But for the past nearly two years of my life, I’ve lived with the weight of a defamation lawsuit on me. That’s an everyday thing, and it’s a lonely thing.” Occasionally, in the middle of the night, she sits up in bed and asks her husband, “What if he tries to take everything?”

This article has been updated with additional information on Pamela Lopez’s comments to the Los Angeles Times, and to clarify that cases of domestic abuse are included in Mother Jones’s database.