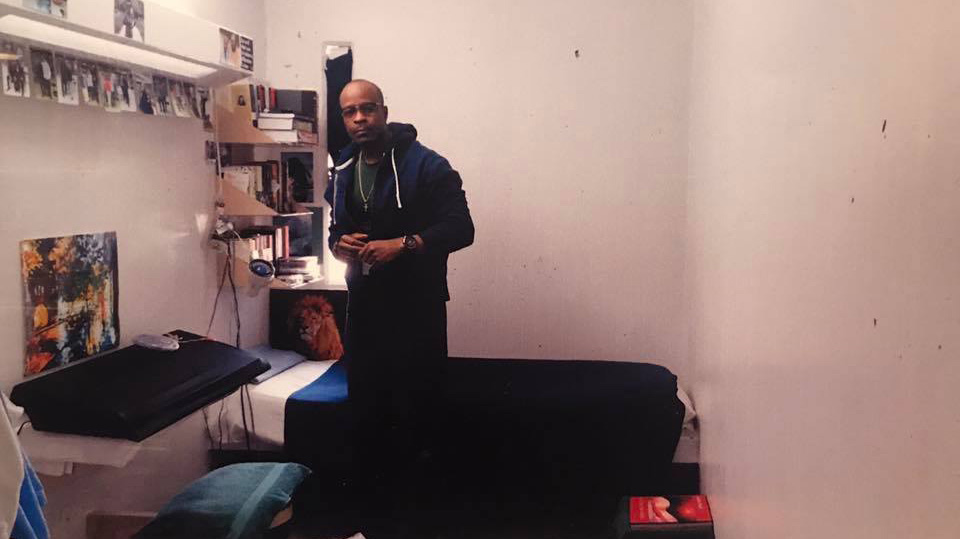

Keith LaMar in his cell, where he spends at least 23 hours a dayJustice for Keith LaMar Facebook

For 27 years, Keith LaMar has survived solitary confinement in a supermax prison in Ohio, isolated for 23 hours a day in a space the size of a bathroom. From his bed, if he crooks his neck at just the right angle, he can look out through a slit of a window a few inches wide at a parking lot. But in all these years, he hasn’t touched a blade of grass or a tree; the closest he’s come to the outdoors is in a below-ground concrete “rec cage,” covered by a steel grate ceiling. If he’s lucky, he might catch a glimpse of the sun.

LaMar, 50, was locked up as a teenager after killing someone in a dispute during a drug deal. A few years later, he was moved to solitary confinement and sentenced to death after he was convicted of murdering five inmates in a prison riot known as the Lucasville Uprising. He says he did not kill them. Activists in Ohio and around the country have rallied to his cause by writing op-eds and staging solidarity actions. His execution is scheduled for 2023.

After a hunger strike in 2011, LaMar and a few other death row prisoners at the Ohio supermax won the right to hug their family members during visits, instead of just seeing them through a plexiglass barrier, and to make phone calls from their cells. Lately, his friends outside prison have been telling him about the spread of the coronavirus and the new “shelter in place” orders taking effect in many states. His friends wonder how he stays positive during prolonged periods of physical isolation. The social distancing they describe is nowhere near as extreme as the punishment of solitary confinement—a form of torture. But he has tried to offer what insight he can. He called me last week from his cell.

In solitary, I’m already quarantined somewhat. The only way we would get sick is if a CO [correctional officer] or somebody brings it in. It’s probably inevitable because the guards, even if they don’t have a temperature, can still be carrying the virus. And they are the ones who pass out mail, who give us food. I’m doing what I can in terms of washing my hands frequently, but there’s only so much you can do. You just sitting here waiting to catch it.

I had a strict rule with my family that if anyone is sick please don’t come visit, because once you get the flu [here] it’s just torture. They don’t give you any medications, beyond ibuprofen, so you pretty much have to suffer through. If you catch something as severe as coronavirus, I don’t know how they intend to deal with that. Perhaps they would ship you out to another facility, a hospital. I’m definitely afraid.

They have suspended all visitations, so our families aren’t able to come. Before, I was getting five to six visits a month: nieces and nephews, my uncles, aunts, friends. I realize there’s a pandemic, so I’m all for suspending visits temporarily. My fear is that after this is said and done, they will use this as an excuse to extend the no-visit policy. I went 18 years without being able to hug my family. That’s the only concern I have, besides getting sick.

People have been asking me questions ever since this “shelter in place,” with people having to stay home. It’s somewhat similar I suppose to being in solitary confinement, even though you might be with family and whatnot. Being in solitary confinement is really just being thrown upon yourself: You’re running around, just like people do in your regular life, and now all of a sudden you’re confronted with yourself, and find that in a lot of cases you haven’t really put anything into yourself to occupy yourself. Everything is outward directed. That’s what happened to me 27 years ago, and what happens to a lot of guys who are initially thrown into this situation—it’s like being thrown into the ocean. You have to learn how to swim. You have to learn how to deal with yourself.

I’ve been lucky in a lot of ways. My cell has a bookshelf with three shelves, and there’s a table to sit and write. I have a lot of music, books to read. Not to distract myself from myself, but to take me deeper into myself. I paint, I work out, I do yoga, I meditate.

I didn’t know I could write. I dropped out of high school in the 10th grade. I was 23, 24 years old at the time I was thrown on death row, at a loss of what would become of me. My education, if you can call it that, has come from my own efforts. I just started reading Richard Wright’s Black Boy, over and over. Paying attention to what he was doing and how. Before I knew what a semicolon was, I saw how he was using it. That’s how I learned to write. And I became an author. I’m not the best writer. My book Condemned probably won’t make the New York Times bestseller list. But that is my story, and I wrote it. And in that way I feel somewhat vindicated, that at least I tried to stand up and say something about my life.

I also like reading about the Holocaust. One of my favorite authors dealing with that genre is Primo Levi. Compared to my situation, his situation was much more extreme. You could die or be sent to the gas chamber on a whim. The arbitrariness of being thrown into those situations—I respond a whole lot to his experience. James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, is also a big influence on my life. And Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me. We’ve got three bookshelves, all three are filled with books. Being in solitary confinement, these books are my community. A lot of these guys, I’ve read their books over and over. So I’m intimately connected to these people. James Baldwin, I consider him like a family member.

I’ve watched quite a few people fall apart, lose their minds. But I went in another direction. So 27 years later I’m still sound in mind and body and spirit. I attribute that to just reading and cultivating myself. That’s the thing, when you’re thrown upon yourself, you realize you are more equipped than you realized. A lot of the system keeps us from realizing our own power. It’s a good opportunity for people to tap into that.

Being in solitary confinement, it’s a punishment. But people out in society, it’s an opportunity for your kids to get more in tune with themselves. Because when you’re in school, especially with the internet being what it is, everybody is generally being pulled away from themselves.

The root word of education is “to educe,” to bring forth that which is already there. Education isn’t really about what kind of career you’re gonna get or how you’re gonna make money. That’s not why we were born, to make money for somebody else. To get a big house. To have a nice car. You’re here to bring forth that which is already there. Hopefully young people being forced to stay home outside of the mainstream curriculum are able to get a glimpse of themselves and start pulling on that thread.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.